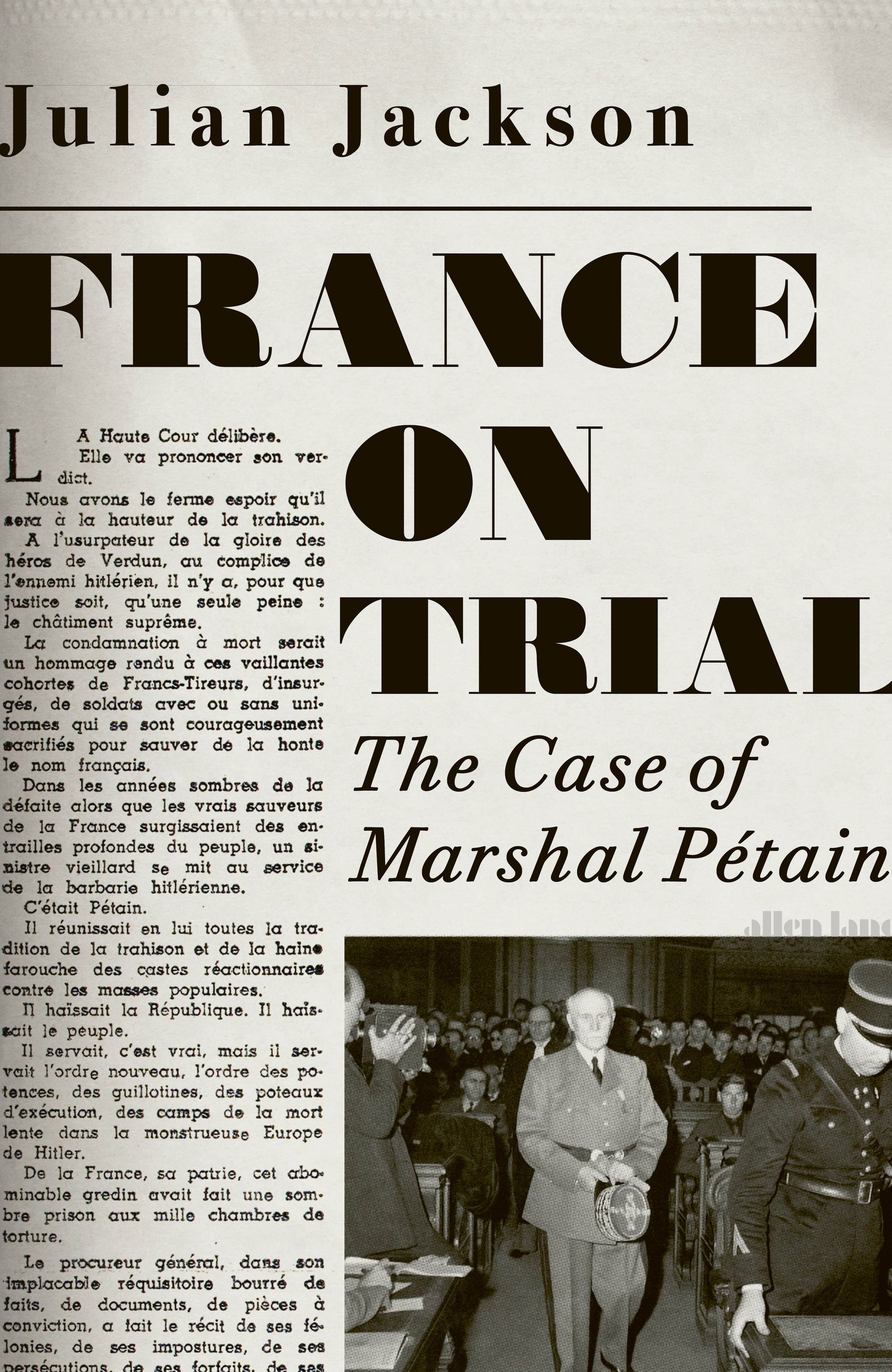

Book review: France on Trial: The Case of

How might Vladimir Putin ever be tried for war crimes in Ukraine? How would a jury of his peers be selected? What atrocities could be attributed to Putin’s own orders or design? What standard of proof would be required?

Sadly, the miserable history of the past century offers many points of reference. The Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals and their Tokyo counterparts set an important marker for principles and procedures, as have Israel’s trial of Adolf Eichmann and the work of international criminal tribunals. We should discount summary justice of the condign sort inflicted on Benito Mussolini and Nicolae Ceaușescu.

France’s trial of a doddery, geriatric war hero is an eccentric entry to this eclectic list of examples. Marshal Pétain, who doggedly refused to lose the Battle of Verdun in 1916, took power in 1940, signed an armistice with the Nazis and presided over France’s collaborationist Vichy regime for the next four years. Just as the Liberation liberated the French from memories of their often-shameful collusion with Germany, so too did Pétain’s trial supply a scapegoat for the errors and crimes committed between 1940 and 1944.

Putin could hardly be tried by his compliant, corrupt Duma, but Pétain had precedent on his side in expecting a trial by parliament. Charles I and Louis XVI were both accorded that right, albeit with purged and cowed assemblies sitting in judgment. Instead, Pétain’s guilt was appraised by an unlikely, unwieldy combination of former parliamentarians and former members of the resistance. Anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny might as well be enlisted as a juror for Putin.

Stalin’s purges are conventionally denounced as show trials because of the absence of due process, the foregone conclusions and the seemingly random selection of many victims.

Nonetheless, any war crimes trial, including those of Albert Speer, Hideki Tojo and Adolf Eichmann, contains an element of show and tell. Julian Jackson in France on Trial: The Case of Marshal éétain designates them as “exercises in national pedagogy”. Their process and record are meant to teach morals, not least by setting limits on acceptable behaviour. For France, Pétain’s trial also provided a biased, partial explanation of why France had suffered the most rapid and total defeat of any Great Power in history.

During his trial, Pétain’s answers blended “evasion, blame-shifting, amnesia and perplexity”. He maintained that, absent an armistice and without a puppet government, France’s fate would have been worse (like Poland’s, say). “If I could no longer have been your sword, I have wanted to be your shield.” Imagine how much more defiantly articulate Napoleon would have been had he been brought to trial.

Notwithstanding the dispiriting ambivalence in Pétain’s three-week trial, about treason especially, Jackson does raise questions relevant today, and tomorrow. When can personal responsibility be dissolved into collective culpability? Where does patriotic duty lie after military defeat? Should trying a leader be a prelude to convicting his accomplices, reaching how far down? Can a legal government properly be considered as void of legitimacy?