The 2022 Lowy Poll of Australian public opinion shows that a record nine out of ten Australians feel the Australia-United States alliance under the ANZUS arrangement is critical to their security. Commitments under ANZUS remain strong. That’s good news.

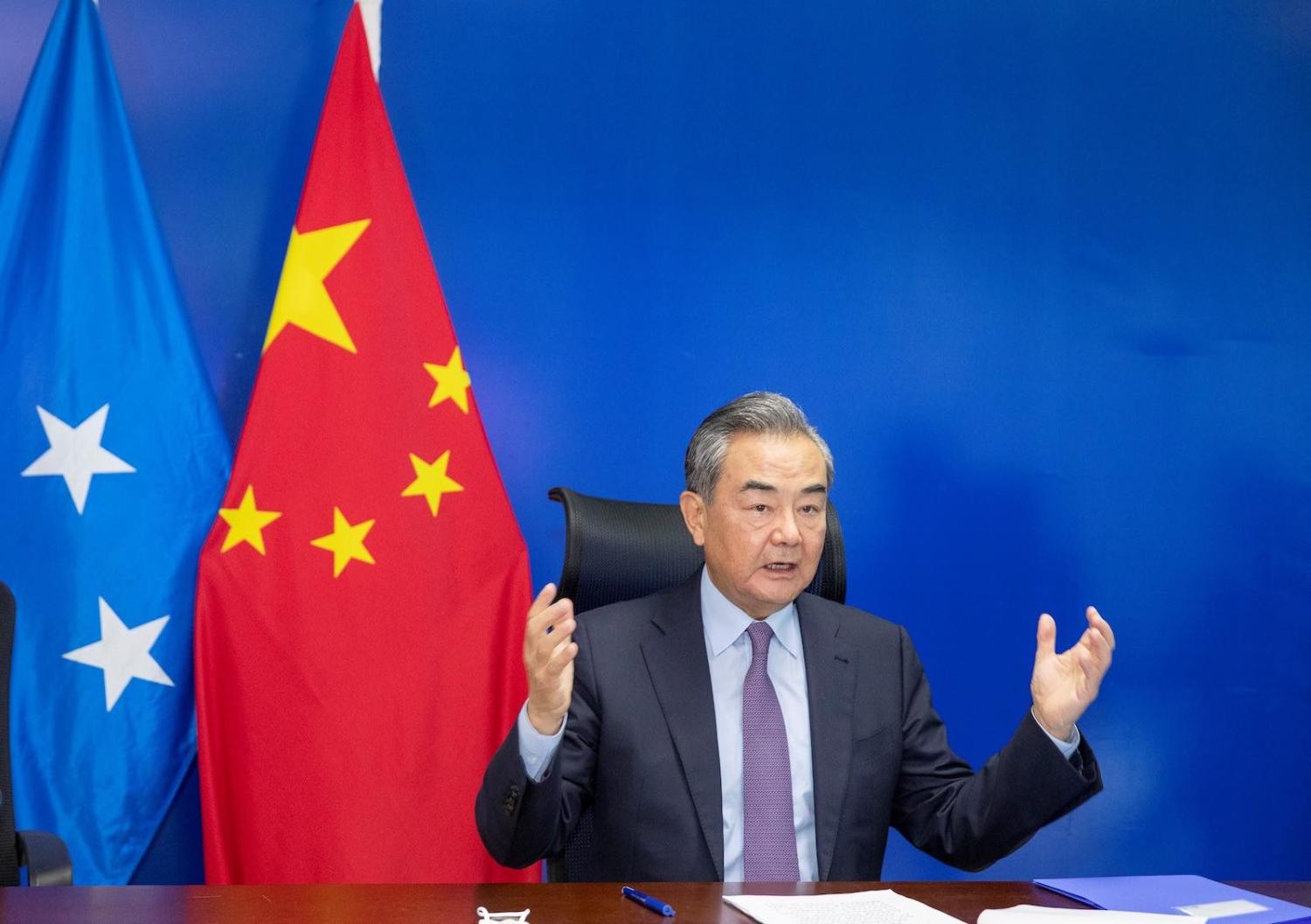

Yet just as many people reported feeling concerned about security in their region, encompassing the Pacific. It’s an understandable anxiety considering the recent signing of a bilateral security agreement between China and Solomon Islands. The agreement potentially gives China an opening to build a military base, in a country that sits close to Australia’s border – although Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare has repeatedly assured there will be no permanent foreign military presence. China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi then took a regional security and trade agreement to Pacific Island nations, one that could fundamentally change the regional order to be more China-centric. The regional agreement was rejected, but reading between the lines of China’s position paper for the Pacific Islands, there’ll be more attempts in the future.

The Australian public’s worry about China’s increasing engagements in the Pacific will not be helped by the intense media coverage of Wang’s tour, in which journalists asked questions of China’s intent. Stories of Australia’s quick deployment to the Pacific of its new Foreign Minister Penny Wong, just four days into her job, also amplified the narrative.

As Australia seeks to find new ways to engage in the region, it should also start to better understand how Pacific Island citizens and leaders perceive Australia’s foreign policy.

Recent admissions by senior US State Department officials – also deployed to the region following the China-Solomon Islands security agreement – indicates the American government also shares the Australian public’s concern about China’s regional ambitions. These officials recognise the need for the United States to “do better … right across the board”, including through more regular conversations with Pacific Island leaders, with humility. The US administration’s focus on other global issues, such as increasing competition in South and Southeast Asia, and the war in Ukraine, partly explains America’s recent absence.

Providing development aid to meet the needs of Pacific Island countries has long been an Australian priority. This year’s poll shows Australians are supportive of that approach. Eighty-two per cent of Australians think Australia should be providing aid, “to help prevent China from increasing its influence in the Pacific” with about the same number agreeing Australia should provide aid for long-term economic development. Australians clearly favour balance in its regional foreign policy – a balance that equally meets Australia’s defence and diplomatic priorities.

The poll indicates that 43 per cent of Australians think a regional focus on Asia and the Pacific should be Australia’s foreign policy priority, while only one in five Australians think Australia should focus on “cooperation with Western countries and traditional partners, including the United States”. These two priorities are not mutually exclusive, and since support for the alliance is at an all-time high, Australian-US cooperation in the region could be broadly welcomed by an Australian public unsettled by recent events in the Pacific.

There are other actors in the Pacific, however, and world leaders far more trusted by the Australian public to “do the right thing” in international affairs than US President Joe Biden. Since 2019, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has topped the candidate list for leaders trusted by the Australian public. Her approval ratings this year are 20 percentage points above the runner-up, French President Emmanuel Macron. Seven in ten Australians also trust France to act responsibly in world affairs, despite the breakdown of formal relationships between the two following Australia’s cancelling of its submarine contract held with France.

Nearly nine out of ten people said they have a lot or some confidence in Ardern. It’s striking then, to compare that positive result with her government’s admission that New Zealand’s relationship with Solomon Islands was a failure. New Zealand’s Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta, who has been in the job since 2020, was also criticised for travelling less to Pacific Island nations than her Australian counterpart did in the first few weeks of taking up her role. Closed borders largely prevented Mahuta’s travel, but many months have passed since they reopened. There is real opportunity, though, for Ardern and her ministers to connect with a broader set of Pacific Island nations than those closest to New Zealand. New Zealand is considered not in, but of the Pacific due to its historical, ethnic, and cultural links with Polynesian communities. And, if her approval rating in Australia is anything to go by, Ardern’s celebrity may prove a helpful deployment.

Trusted leadership and official visits to Pacific Island nations are not enough though, and Pacific Island leaders are calling for more action and results from all development partnerships, including China. The numerous signed and unsigned agreements China has presented demonstrate how far Beijing is willing to go to meet those calls, and where some opportunities lie for Australia and its allies to provide a more trusted, quality deal.

As Australia seeks to find new ways to engage in the region, it should also start to better understand how Pacific Island citizens and leaders perceive Australia’s foreign policy. A poll across Pacific Island countries – such as that conducted by the Whitlam Institute in Papua New Guinea – could help shape the way Australia does business there, just as the Lowy Poll shapes Australia’s domestic debate. Pacific Island perspectives would be an important contribution to Australia’s response to what nearly nine out of ten Australians believe to be the country’s biggest concern: regional security.