Concerns ahead of Cambodia’s elections on 29 July centre on the judgement that under Prime Minister Hun Sen the country has become increasingly authoritarian in political character while the government – through a range of parliamentary and judicial actions, and backed by absolute control of the forces of order – has eliminated any viable political opposition to ensure its electoral return.

How did we arrive at this state of affairs in which there is now very little external actors can, or will, do to prevent Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party staying in office? Even if an unlikely election result occurs, with Hun Sen’s government voted out, it seems certain he would use all means, including force if necessary, to remain in power.

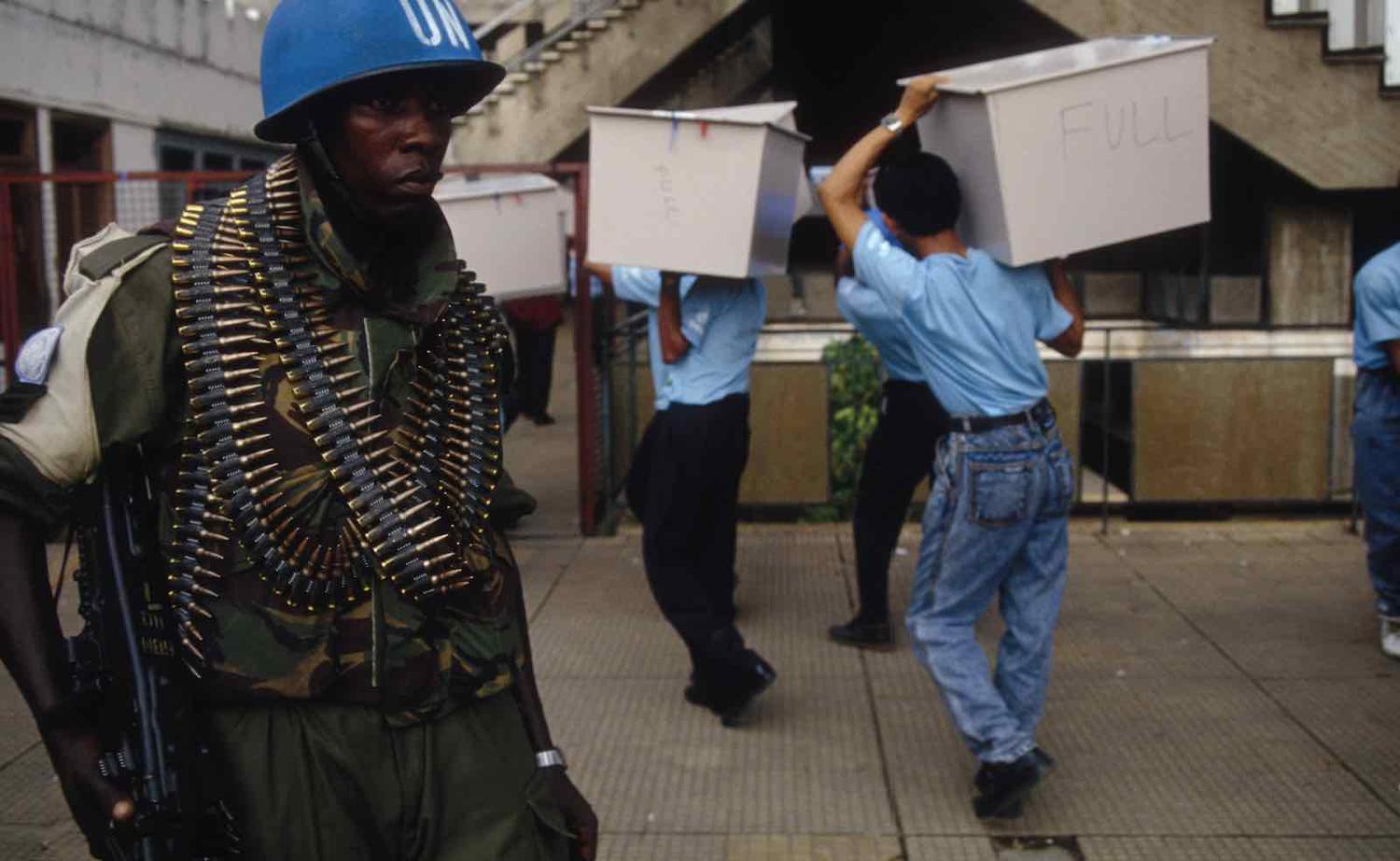

A brief review of Cambodia’s political history since the UN-supervised elections of 1993 is needed to understand the present situation.

Everything suggests that Hun Sen has set his course and will not be deflected from it.

The “original sin” that led to this set of circumstances occurred when the international community stepped back from involvement in Cambodia’s affairs and allowed the CPP to remain the dominant political force in the country, despite having lost the popular vote in the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC)–supervised elections in 1993. With Hun Sen and the CPP refusing to accept defeat, the compromise arrangements that were cobbled together left all real power in their hands.

As David Chandler notes of the political opposition at the time in his A History of Cambodia, “The royalist party soon lost its voice in decision making as well as its freedom of manoeuvre.”

Tired of the problems in Cambodia that had been exercising Western governments for more than a decade, no external players intervened to change the course of events. Similarly, there was never any sign at that stage that Moscow and Beijing had any interest in becoming directly involved in opposing the CPP’s actions.

The complex political history of the period from 1993 to 1997 is well documented in David W. Roberts’ Political Transition in Cambodia: Power, Elitism and Democracy. A disclosure: I reviewed this book for Pacific Affairs in 2001 and commented that it could be read as a justification for Hun Sen’s political behaviour. But I found persuasive, then and now, his endorsement of a view offered by long-term observer of Cambodia Steve Heder that the key players of the period – Sihanouk, Sam Rainsy, and Ranariddh – were all characterised by “deeply illiberal, anti-democratic and anti-pluralist tendencies”.

This lack of action in 1993 was followed by the unwillingness of external players to take any measures that mattered after Hun Sen’s brutal coup de force in July 1997 that saw the CPP overwhelm Prince Ranariddh’s FUNCINPEC.

Roberts tellingly quotes Henry Kissinger as asking rhetorically in 1998, “Why should we [the West] flagellate ourselves for what Cambodians did to each other?” Then UN secretary-general Kofi Annan claimed in 1997, shortly after Hun Sen’s coup, that the UNTAC intervention was “successful in helping to establish national institutions which could lead to stability and economic development”. This latter comment seems to typify the worst kind of readiness of an international civil servant to gloss over the realities of a complex set of circumstances.

The sanctions that followed the events of 1997, which included the US Congress cutting off aid to Cambodia and ASEAN postponing the admission of Cambodia to membership, also marked the beginning of Hun Sen’s ever closer relations with China. Having helped the Khmer Rouge for decades – before, during, and after the period of Pol Pot’s rule – Beijing now changed its policy and embarked on support for Hun Sen and the CPP, which continues to the present day.

It is China’s support that has enabled Hun Sen to weather repeated criticisms of his regime while building up the military strength that ensures his survival. The return for this Chinese largesse has been Cambodia’s reliable support for its foreign policy objectives, most notably in relation to the South China Sea. And Hun Sen has never ceased to contrast Chinese aid offered “without strings” with aid from Western nations tied to conditions.

Analysis of the 2013 national election, in which the CPP’s vote declined significantly, suggested that social media and the voting pattern of younger Cambodians had begun to play an important part in shaping political opinion. These facts might explain the serial courses of action that Hun Sen has taken to neuter any effective political challenge from his opponents, most particularly the dissolution of the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party.

Everything suggests that Hun Sen has set his course and will not be deflected from it. In doing so he is showing himself more inclined to double down on authoritarian action than to reflect his little known chess playing abilities. And there is no reason to think any external player that matters will do anything to divert him from his present policies.