Is Afghanistan any longer a State in the international system under international law? More particularly, is the Taliban capable of being recognised as a legitimate government?

These are not just technical legal issues. They are ones that have already been raised and have political consequences. Soon after the fall of Kabul to the Taliban, Britain’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson urged coalition partners to exercise caution in recognising a Taliban government. Some commentators, such as David Kilcullen, have suggested that both China and Russia had effectively conferred de facto recognition on the Taliban by 20 August.

International law establishes well recognised criteria for the recognition of a newly emerged State. The 1933 Montevideo Convention test is that a new State possess i) a permanent population; ii) defined territory; iii) a government; and iv) capacity to enter into relations with other States. Australia relies upon and applies the Montevideo Convention criteria when determining the existence of a State. This test was applied following Timor-Leste’s 2002 independence and when other new States have emerged such as South Sudan.

Whether a government is democratically elected or a dictatorship is of no concern to international law regarding statehood.

The Afghanistan of today is no different than that of a month ago on the basis of these criteria. There is clearly a permanent population. Yes, many are currently seeking to flee the country but that does not impair the core stability of Afghanistan’s population. The country also has settled borders that are broadly recognised by neighbours.

The previous government of Ashraf Ghani may have fallen, but it would appear that a new Taliban government is in the process of being formed. The presence of a functioning government capable of exercising certain levels of control over the State is an aspect of the Montevideo Convention criteria. This could extend to the defence and security of the State. However, importantly, the criteria seek to make no judgement, for the purposes of international law, as to how the government came into existence, the longevity of the government, or the political system which is the basis for governmental control. Accordingly, whether a government is democratically elected or a dictatorship is of no concern to international law regarding statehood.

In terms of the ability of the Taliban to enter into relations with others there is evidence that this is already occurring. In 2020 the Trump administration famously entered into an agreement with the Taliban which was designed to provide a road map for US military withdrawal. While carefully crafted to reflect the reluctance of the US to formally recognise the Taliban, the reality is they are the only authority that currently have the capacity to allow the US-coordinated military airlift to proceed.

State practice and academic commentary suggest that in addition to the Montevideo Convention criteria other factors may from time to time be taken into account.

Permanence is one criteria, suggesting that a new State must have a continuing capacity to be able to satisfy the criteria. Afghanistan has been independent since 1919 and notwithstanding the many challenges it has faced its permanence cannot be questioned.

Willingness and ability to observe international law has also been cited as a criteria. This will certainly be under active consideration given the Taliban’s history of human rights abuse.

Australia changed its recognition policy in 1988 to only recognise States, and not States and governments.

The extent to which recognition has been granted by other members of the international community may also be a factor. Australia changed its recognition policy in 1988 to only recognise States, and not States and governments. The policy change, which reflected a trend in practice at that time, has been continued by successive Australian governments. Accordingly, Australia now only formally recognises the emergence of new States into the international system. Likewise, Australia does not seek to formally recognise either governments or political parties which purport to exercise some form of control over territory, as reflected in the position which has been adopted from time to time with respect to certain groups in the Western Sahara, or the Kurds in Iraq. Some nuance appeared in Australian policy in 2019 when the Morrison government decided to formally recognise Juan Guaidó as interim President of Venezuela in a move that aligned with the actions of other western partners.

On the basis of Australian and international practice and the actual circumstances in Kabul, Australia would appear to have two options: 1) continue with full de jure recognition of Afghanistan and by default of a Taliban government; or, 2) continue with full de jure recognition of Afghanistan and grant de facto recognition to the Taliban as the government.

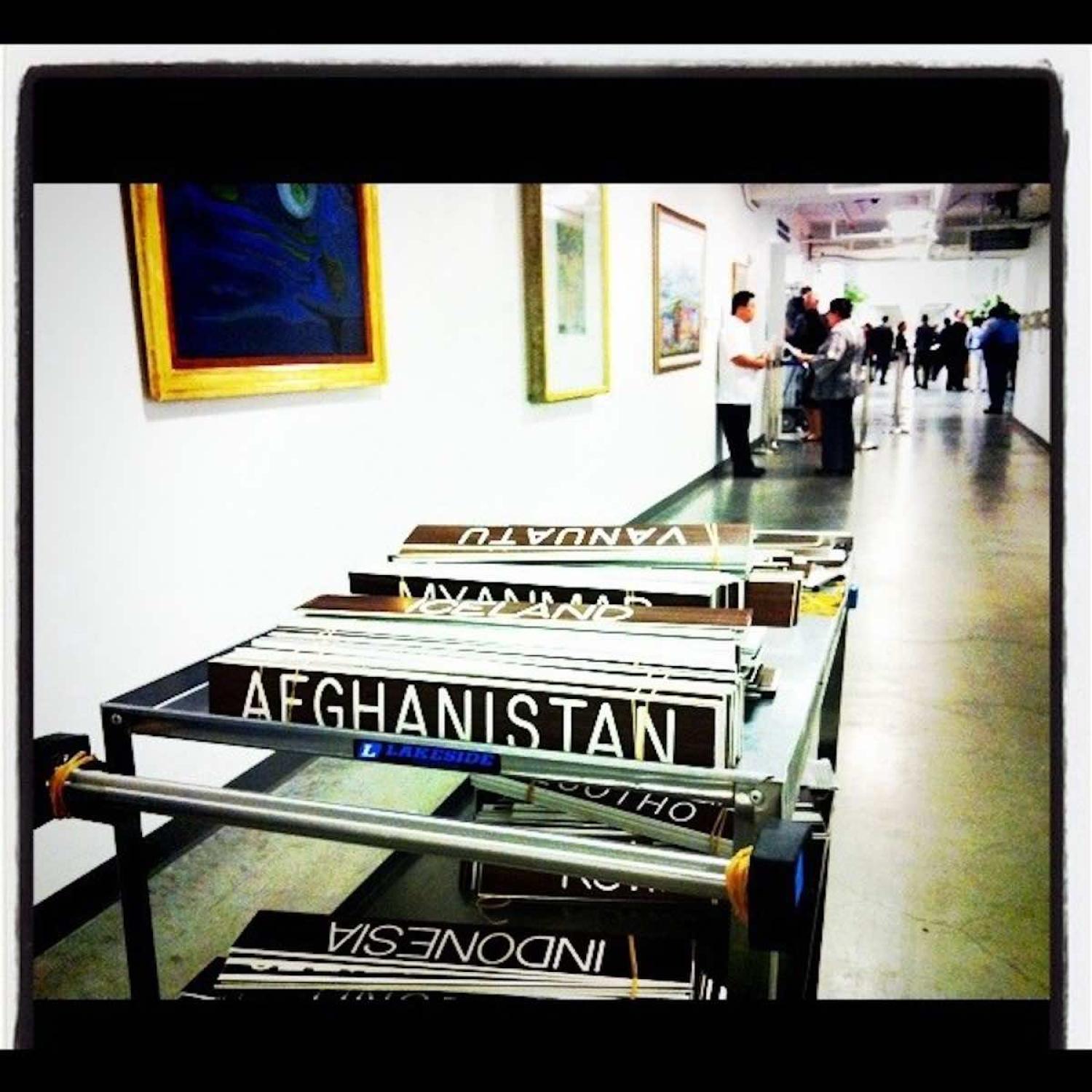

The first option would be consistent with the view that Afghanistan as a State currently meets the Montevideo Convention criteria for the purposes of international law. As such Canberra should be prepared to grant recognition to the Taliban as the new government consistent with Australian practice. This approach would align with how Australia responded to the 1 February coup in Myanmar. Relations with Myanmar have been strained following the coup but Australia has not withdrawn recognition of the country or its military rulers.

Alternatively, granting de facto recognition to the Taliban as the government of Afghanistan would only be an indication of Australia’s qualified support for the Taliban. Under this option Australia could indicate conditions that it would expect the Taliban to meet prior to de jure recognition being granted. This option would represent a qualification to Australia’s recognition policy which could be justified on the basis of the exceptional circumstances associated with the situation in Afghanistan and the Taliban’s previous track record when in power.

The 24 August virtual G7 summit hosted by the United Kingdom has suggested that a road map exists for Afghanistan. Withholding recognition of the Taliban until such time as the military airlift is completed may well be one condition. Whether other conditions will be set by the United States, United Kingdom, Australia and others remains to be seen. If that does occur then requiring a Taliban government to adhere to human rights standards and especially those of women and children would be justifiable.