Concern over the possible decline of US power and the resilience of its commitment to underwriting security in Asia is not new. In the post-1945 period, doubts over Washington’s commitment to maintaining a leadership role in the region have followed President Nixon’s shift to the Guam Doctrine in 1969, eventual defeat in Vietnam in 1975, the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, and the Bush Administration’s preoccupation with the Middle East post-9/11.

With China’s capacity to project economic and military power growing daily, and Beijing’s apparent goal of challenging US strategic preeminence in Asia, these concerns have once more been raised. They have emerged as a feature of foreign policy debate in the US and throughout Asia, including in Canberra and Tokyo.

What makes this latest round of concern different to that of prior decades is the sharply unconventional, unprecedented, and highly unpredictable thinking of US President Donald Trump. As Michael Fullilove has observed, ‘the leader of the free world has a narrow conception of leadership and may not even believe in the free world’. Indeed, Trump is the first post-1945 president not to clearly endorse the long-standing US commitment to maintain the liberal international order it has relied on both for the pursuit of its own interests, as well as a wellspring of legitimacy for US leadership.

The persistent ambiguity over what the Trump Administration is committed to in its foreign relations (other than putting ‘America first’, whatever that might mean) has caused major conniptions in various capitals, but there are some signs that normal service may be resuming in the White House (at least in Trump’s thinking on Asia, if not yet on Europe). His reaffirmation of the ‘One-China’ policy and soothing assurances for Japan and South Korea have been welcomed. But many remain rightly suspicious of Trump and the ability of the US political system to rein in his maverick behavior over the next four years. So far, built-in checks and balances seem to be mostly working, but for how long remains uncertain.

Last December in Tokyo, the annual Australia-Japan Dialogue (jointly hosted by the Griffith Asia Institute and the Japan Institute of International Affairs) brought together experts from Australia, Japan, and the US. T to consider the nature of the Australian and Japanese commitment to the US as guarantor of the current Asian security order and how shared interests underpinning that commitment can best be managed in the future. These types of questions are fundamental to Australian policy thinking, since so much of our outlook and ambition has been predicated on continuing US extended deterrence and support for the region’s liberal order. They merit careful consideration under Canberra’s upcoming Foreign Policy White Paper, especially given that major change is underway in the region and has been for some time.

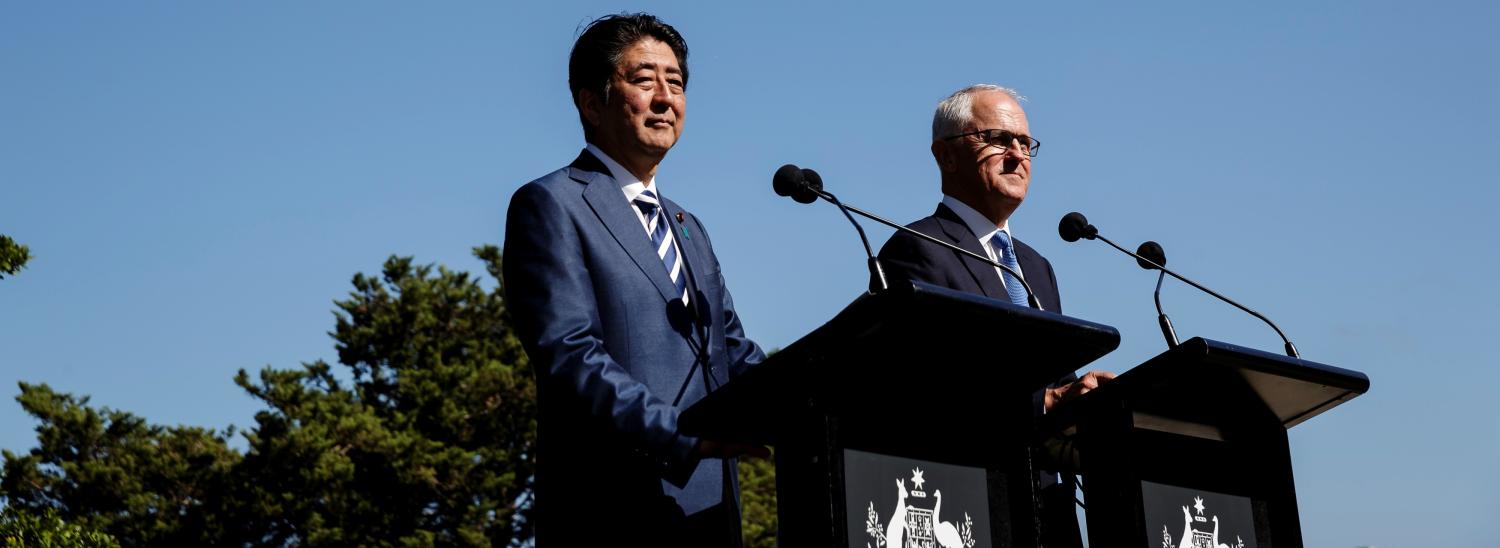

Indeed, Trump’s shock election only a few weeks the Dialogue threw an entirely different light on the original theme and questions that had been set out for discussion. But many of the same issues, while subsequently carrying a different order of concern and urgency, were already on the table even with the expectation that Hillary Clinton would be elected. Keeping the US engaged, growing irritation in Washington over perceptions of free-riding allies, and managing a tougher line on China are challenges the Abe and Turnbull governments would still be facing, regardless of who won last November. The major difficulty posed by Trump’s Presidency is dealing with these issues in a context where the value and commitment Washington attaches to its regional alliances appears to be far more negotiable than before.

The overriding themes that emerged from the Dialogue regarding how Australia and Japan can best manage their relations with the US, taking into account the Trump wildcard, were founded on the following assumptions:

1. Managing the uncertainty over US foreign policy and Washington’s long-term commitment to Asia is the immediate challenge facing Australia, Japan, and other US allies in the broader region. How the Trump Administration calibrates US strategic engagement, particularly with respect to reassuring allies through extended deterrence, expectations over burden-sharing, and whether Washington remains fully focused on the region when other theatres like the Middle East become a priority are all sources of uncertainty.

2. Uncertainty over the depth of, and possible limitations placed upon, US security commitments to allies will continue to be a major factor shaping strategic thinking in Canberra and Tokyo. Trump’s decision to trash the US commitment to the TPP with minimal (if any) consultation with Asian allies is a very worrying sign, since similar indifference may also characterise his Administration’s approach to alliance management on other important issues, such as North Korea’s WMD program, China’s posture on territorial disputes, and the promotion of liberal democratic values in Asia.

3. Australia and Japan remain strongly committed to their alliances with the US and to supporting continued US leadership of the current order. Although the post-war ‘hub-and-spokes’ bilateral alliance system is becoming outdated, Australia and Japan’s bilateral relationship (and trilateral relations with the US through the highly successful Trilateral Strategic Dialogue) will be more important than ever in promoting shared security and political interests in Asia.

A major White Paper takeout from the Dialogue is that increased security cooperation between US allies with support from US security partners in the region (e.g., Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia and India) could be very effective not only in satisfying demands from Trump and future administrations for a bigger contribution from allies (and therefore encouraging ongoing US support), but also as a hedge against a possible drawdown of US strategic engagement in Asia. Increasing the tempo of strategic cooperation among like-minded states also is likely to provide a stronger platform for greater regional influence on policy thinking in Washington.

How Trump would react to a major black swan event, such as 9/11, is a worrying proposition. One only has to recall the abrupt, and ultimately disastrous, policy shift under the Bush Administration following the al-Qaeda attacks on New York and Washington to appreciate how a capricious and monochrome individual like Trump (and his senior advisers of decidedly mixed quality) might react. Thus, even long-standing and highly regarded US allies such as Australia and Japan need a Plan B.

This is not a plan involving any realignment or downgrading of support for US leadership, but instead a plan that allows Canberra, Tokyo, and other like-minded Asian states to prepare effectively for the many unknowns (both known and unknown) that surround America’s future role in Asia, with or without Trump as Commander-in-Chief.