Western governments have long complained about the lack of reciprocity in dealing with China. As the traditional basis for international relations, reciprocity suggests that benefits and penalties alike, granted from one state to another, should be returned in kind.

In diplomatic relations, Chinese ambassadors expect – and agitate – to meet foreign ministers. But foreign ambassadors to China are generally given access to much more junior officials.

As a result of its developing country status, China is the beneficiary of special treatment in the World Trade Organisation. China is entitled to more relaxed environmental protections under various treaties and defends its human rights record on the basis of this status – despite now being the world’s second-largest economy. Western governments have catered to various demands in trade and elsewhere, based on the principle that the benefits of engagement with China outweighed the drawbacks.

We are now at a point where China’s state broadcaster is able to beam news programs that often amount to little more than propaganda into the living rooms of Americans and Australians. By contrast, access to most foreign news services, including the New York Times and the ABC, is banned in China.

Foreign journalists in China are in some cases subjected to harassment and visa delays, and risk being kicked out of the country when visas are refused. Chinese journalists are generally welcomed to other countries, although there are increasing levels of scrutiny under foreign interference legislation.

In diplomatic relations, Chinese ambassadors expect – and agitate – to meet foreign ministers. But foreign ambassadors to China are generally given access to much more junior officials at director general rank (or perhaps the vice minister, if you are the US ambassador). Chinese officials have walked out in protest of international meetings when they are not accorded the same status as ministers.

But 2018 saw changes in the US approach to China. In trade relations, the US has demanded more reciprocity from China. And in December last year, more than five years after it was first introduced by Democratic Representative James McGovern, the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act of 2018 was signed into law.

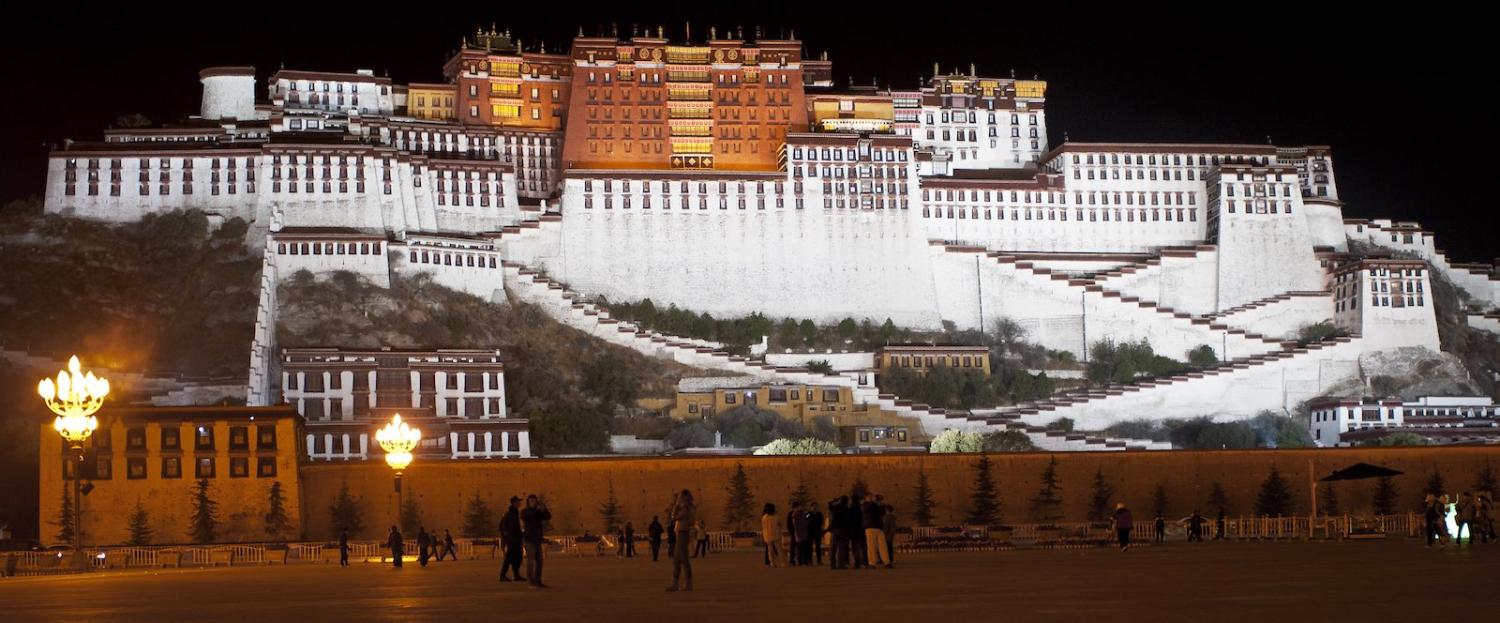

This law essentially brings the concept of reciprocity back to the table, when it comes to access to Tibet. China restricts foreigners from travelling to Tibetan areas – in some cases, by regulation, and in others, by intimidation.

Foreign tourists can travel to Tibet with a tour group at particular times. Journalists and diplomats can only visit Tibet at the invitation of the Tibetan government.

But the new US law stipulates that any individual “substantially involved” in the formulation or execution of these restrictions in Tibet cannot visit the United States, as long as these restrictions remain in place.

This week, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo is required by the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act to deliver to Congress a report that explains the level of access granted by the Chinese government to Tibetan areas.

He will likely report that foreigners still cannot visit Tibet without permission from Tibetan authorities. The Tibet Autonomous Region is currently the only area in China that requires separate approvals for foreign tourists, foreign residents and, accredited foreign journalists, or diplomats in China.

He will remind Congress that China prevented US consular officials from attending to a 2013 bus crash in Tibet for more than two days, where three US citizens had died, in breach of China’s obligations under the Vienna Convention. Similarly, US consular officials struggled to provide consular assistance to US citizens trapped during a 2015 earthquake in Tibet.

He will probably also point to the increased barriers that Tibetans living in the west face when trying to visit their homeland.

Will this Reciprocal Access Act inspire some reciprocity from the Chinese system? It’s possible the Tibet Foreign Affairs Office is scrambling to arrange a delegation from the US Embassy in Beijing before Pompeo delivers his report.

But that seems unlikely, given senior government officials are now claiming that Chinese travel restrictions are in place in order to benevolently protect foreigners from the dangers of altitude sickness. This claim is particularly absurd given the neighbouring Qinghai province has many areas higher than Tibet’s capital Lhasa and is not subject to the same formal restrictions. The same official from Tibet complained that the US Reciprocal Access Act “had seriously interfered in China’s internal affairs”.

The more likely outcome from this Act’s passage is a reduction in visits to the United States by Tibetan delegations. The Chinese system may be sufficiently incensed by this to improve consular access for the US Consulate in Chengdu, which is responsible for Americans in Tibet.

More than anything, this Act will have the Chinese system watching with concern the congressional push for direct sanctions against individual Chinese officials in Xinjiang, where the Chinese government has interned between 1 and 1.5 million Uighurs.

The Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act won’t change the plight of millions of Tibetans or relax the restrictions on foreigners visiting the region. But there are some signs that outside pressure can move Beijing in the right direction.

Chinese officials now know that the United States is, at times, willing to legislate for reciprocity. China’s days of treating the United States as a peer and expecting special treatment at the same time may be limited.