This past month, two progressive female political leaders – Jacinda Ardern, Prime Minister of New Zealand, and Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the US House of Representatives – willingly gave up power and moved to the back benches of their parties.

Ardern’s resignation surprised many because she was leaving before her term ended and because she was well-respected globally as New Zealand’s calm and empathetic leader. But Ardern’s personal popularity had waned domestically, and her party looks likely to lose the October 2023 election.

Pelosi’s resignation was expected in part because the Republicans won a narrow majority in the House (though she stayed under these conditions in 2011) and in part because she promised those who challenged her return to the Speakership in 2019 that she would leave after 2022.

However, practicalities aside, both were graceful exits, and soothing to watch given the fragile state of democracy around the world.

Pelosi and Ardern leave powerful positions knowing that the overall diversity of their caucuses has meaningfully improved under their leadership. Both confronted sexist questions on a regular basis – Ardern for being a younger woman wielding power and Pelosi for being an older woman wielding power – and generally left their questioners looking foolish. And sadly, Pelosi and Ardern share the burden of being prominent targets of violent political speech.

But it is the differences between these two women that is most interesting. A side-by-side comparison provides some texture and nuance to discussions about how women, and in particular mothers, navigate political leadership.

Pelosi has lived nearly twice as many years as Ardern, and when declaring that she would not run to lead her party again, she had been in a leadership position for 20 years and in Congress for 35 years. When Ardern announced her resignation, she had been Prime Minister for nearly six years, and in parliament for 15 years. Ardern gave birth to her first child while serving as Prime Minister four years ago. Pelosi didn’t enter Congress until after her five children were grown.

Ardern’s explanation of why she was choosing to step down as Prime Minister resonated with women around the world who understood or could easily imagine what it feels like to pursue a mission-driven career in a high-pressure environment that leaves a person both exhausted and extraordinarily grateful for the opportunity. We don’t know what role Ardern’s relatively new motherhood played in her decision, but it’s hard to believe it was irrelevant.

It was easy to empathise with Ardern when she briefly choked back tears during her announcement. It seems likely that she is both certain that leaving political leadership is the right choice for her at this moment, and certain that she has only begun to affect the kind of change she would like to see in the world. Ardern’s domestic policy agenda was largely superseded by the requirement to respond to multiple crises such as the terrorist attack on two Christchurch mosques, a volcanic eruption, and the pandemic. Ardern has no plans for the immediate future, which is likely a relief and a somewhat unsettling place to sit.

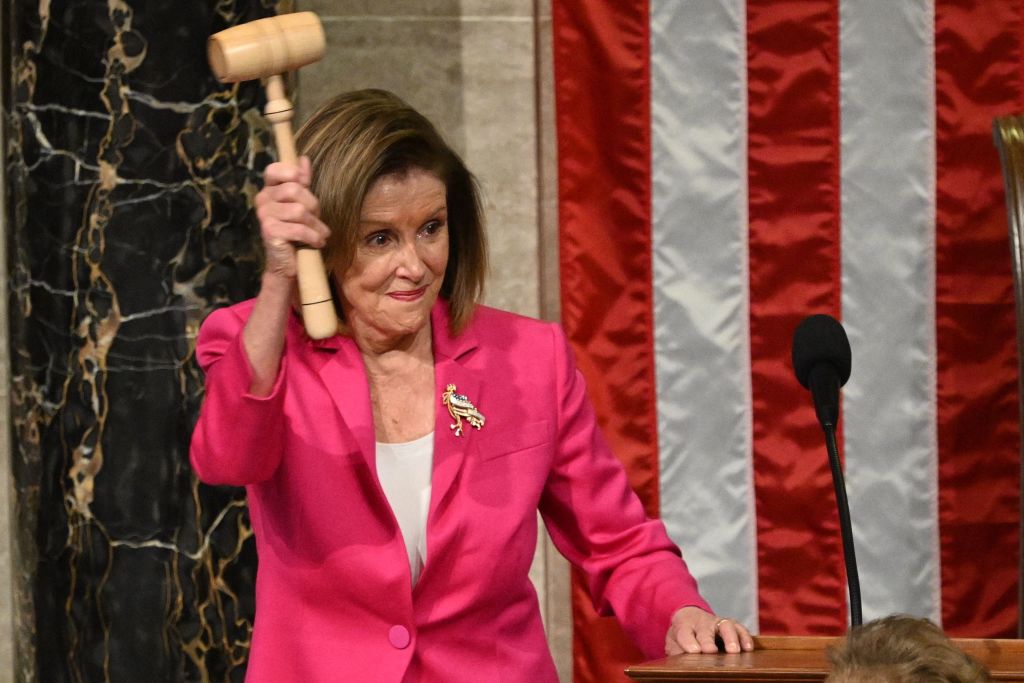

Pelosi, on the other hand, stepped back from political leadership last month with a sense of triumph, an unparalleled record of legislative productivity, and general agreement that she was the best Speaker of the modern era. Her time as leader included working on a bipartisan basis to address the financial crisis, the pandemic, infrastructure, aid to Ukraine, and protection for same-sex marriage, and working with the Democratic majority to deliver health care reform and the biggest climate measure ever enacted. During the Trump administration, Pelosi served not only as a much-needed foil to Donald Trump, but as a day-to-day check on his power.

Pelosi was raised in a political family (her father served in Congress and as Mayor of Baltimore), but she is unequivocal in crediting her younger self – the one who raised five children – with preparing her to be Speaker of the House. When she recruits mothers to run for office, she tells them that the Democratic party – an unwieldly and diverse caucus – requires the skills they possess: the capacity to manage chaos, command, delegate and motivate difficult people.

But it’s important to consider the time and heartache associated with Pelosi’s time in leadership. In her first stint as Speaker in 2007 Pelosi spent two years waging an unsuccessful campaign to cut funding for the Iraq war. And the flip side of her greatest accomplishment – passing the Affordable Care Act – was the dramatic conservative backlash against the bill.

This backlash sent her into the minority for eight years and continues to stymie the ability of the Congress to function. Further, Pelosi spent the first two years of the Trump administration in an all-out battle to save the Affordable Care Act from repeal. The legislation escaped repeal but Pelosi didn’t save it, and the legislation remained vulnerable to executive actions.

Pelosi’s filmmaker daughter Alexandra recently released a documentary that covers the last three decades of her mother’s life. It’s clear that Pelosi replicated the political life she knew as a child with her own family in which legislative work and political organising permeates much of their time together. Pelosi’s adult children appear to genuinely adore her, which is a feat under any circumstances. But this life would not work for everyone.

There are no straightforward takeaways from the Ardern and Pelosi comparison. In fact, that’s the point. With the example of these two women, we simply see the myriad different ways that a woman might combine motherhood with political leadership. These are but two.