This is a discussion thread marking the Lowy Institute Media Award, which each year recognises excellence in foreign affairs journalism. Click here to see the short list for this year’s award. The winner will be announced on 23 September.

Editors don't occupy the top rung of the journalistic ladder. Foreign correspondents do. Their exploits, real and imagined, have inspired the careers of legions of reporters down the years. And not just reporters. Authors and publishers, screenwriters, directors and playwrights all get in on the act. They imbue their heroes with virtues, again real and imagined, that speak to the romance, derring-do and hard-won, worldly wisdom that we unconsciously assign to those reporters designated 'Foreign Correspondent'.

Although my career as a working reporter was short-lived, I was not immune. As a 17-year-old copy boy I spent night shifts on a stool in a corner of the sub-editors' room. At my shoulder hummed the pneumatic tubes through which I sent copy speeding to the compositors and linotype operators next door. Behind me was the telex room, its row of clattering machines churning out all the news that was fit to print from the four corners of the world.

I was privileged to witness this last gasp of 19th century newspaper tradition because within a year it had vanished, replaced by computers.

But as the callow lad I was, I spent more than a few of those long nights (between making pots of stewed tea and fetching page proofs and smokes for the subs) imagining my own future covering wars, coups, famines and other stock-in-trade of the fabled 'Foreign Correspondent'.

Alas, it wasn't to be. And, of course, anyone who has actually been a foreign correspondent can quickly demolish the notion that it's all it's cracked up to be.

In my time, the 'Tiser's beloved cadet counsellor Bob Jervis did his best to set us pups straight with recommended reading lists.

We'd all read Evelyn Waugh's Scoop already, and that, we were assured, told us almost everything we needed to know about the mysteries of foreign reporting and how news was really made.

But there were other must-reads that would fill out the picture. Books like Edward Behr's arrestingly titled Anyone Here Been Raped and Speaks English? , a 1978 account of 'the horror and humour, competitiveness and camaraderie' of that veteran's 30-odd years 'behind the lines'. Or Michael Herr's 1977 memoir of the Vietnam War Dispatches, described by John le Carré as 'the best book I have ever read on men and war in our time'.

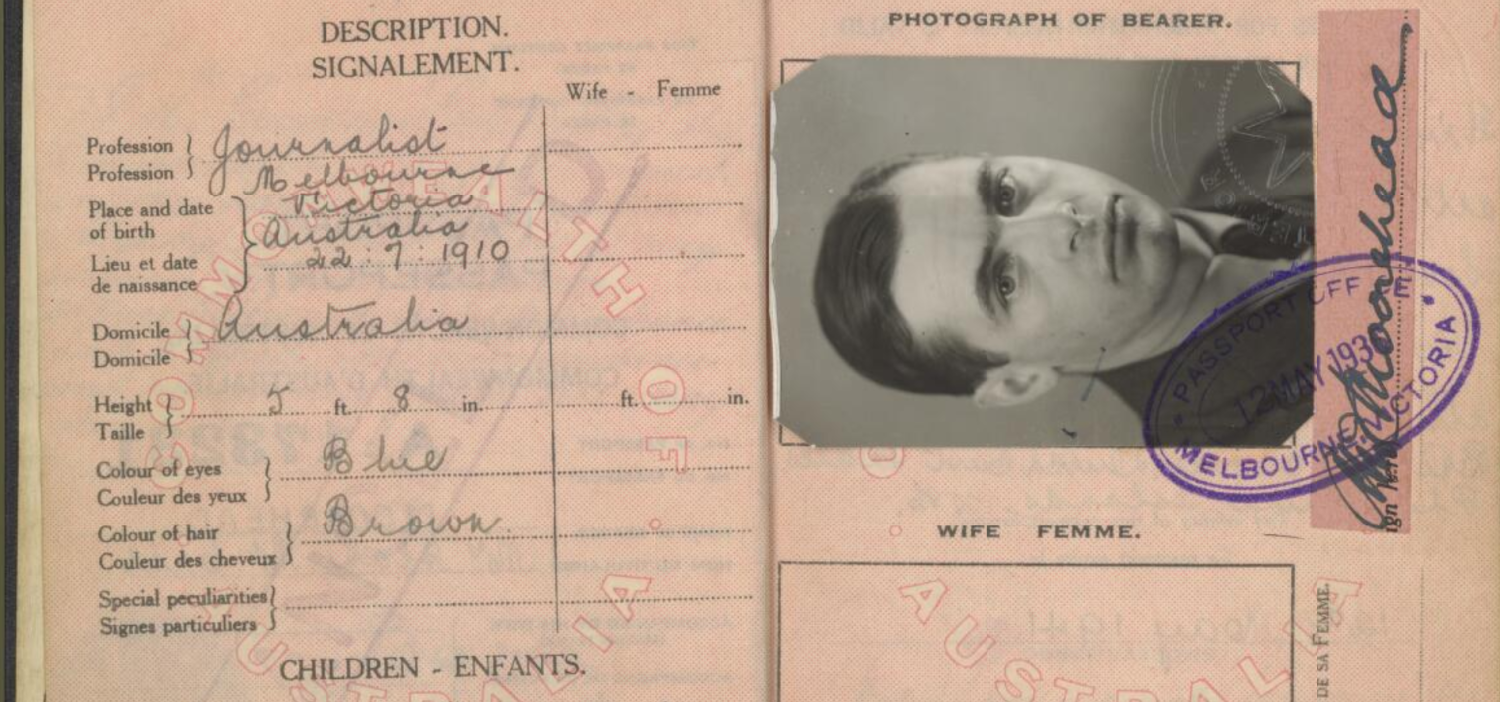

Another was A Late Education (1970), the slim memoir of Australian journalist and author Alan Moorehead. I re-read it recently and marveled again at the elegant and understated account of a reporter who covered most of the 20th century's great historical events and whose life was lived mostly abroad, and mostly on the road. That led me to Thornton McCamish's biography of Moorehead Our Man Elsewhere (2016). For all its style and sophistication Moorehead's memoir doesn't do his life justice. McCamish's biography does.

I built a growing bedside tower of foreign corro' books as I prepared to judge, with four colleagues, the Lowy Institute's annual Media Award, established five years ago to recognise an Australian journalist who has deepened the knowledge, or shaped the discussion, of international policy issues in our country.

Some are classics like Graham Greene's The Quiet American (1955) and Moorehead's African Trilogy (1945); others are newer contributions to the genre, like Leslie Cockburn's Looking for Trouble: One Woman, Six Wars and a Revolution (1998); Naked in Baghdad: The Iraq War and the Aftermath as Seen by NPR's Correspondent Anne Garrels (2003); and Zoe Daniel's Storyteller (2014), a memoir of her time as the ABC's South East Asia correspondent.

Other homework has included re-reading lectures delivered at previous Award nights by distinguished and well-credentialed speakers Nick Warner, Malcolm Turnbull, Robert Thomson and Michelle Guthrie – all Australians.

Each lecture was an informed, thoughtful and entertaining reflection on the art and science of reporting on international events. Each conjured up a sense of what it means to be a foreign correspondent, in particular an Australian foreign correspondent.

Each applied the right touch of nostalgia, that indispensable ingredient when contemplating foreign correspondents. But each also offered unflinching insights about what reporting means in this era of citizen journalism and the iPhone.

Later this month we will hear from an equally distinguished and well-credentialed speaker, this time a non-Australian, when Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times columnist Bret Stephens will speak on the role of the press in the age of Trump. Bret's audience in Sydney, and the rest of the world, waits for him to make sense of it all. Based on his acclaimed Daniel Pearl Lecture, it will not be a speech to miss.

Every year the judges of the Award spend an increasing amount of time discussing how the upheaval in reporting methods and technology is changing the way news is gathered and consumed by Australians, and how it presents new challenges for reporters and their news organisations.

Every year we fail to come up with neat answers. But no matter. The Award exists not to solve these problems but simply to recognise the best of what foreign correspondents have always done – to deliver the facts in compelling ways and in so doing help make sense of the world.

And you don't have to be stationed in Beijing, Kinshasa or Washington to do that. In 2015 The Australian's Paul Maley won the award for his outstanding and sustained reporting on the impact of foreign fighters on Australia. He did almost all of it from Sydney.

The award process – coming up with suggestions for the long list; the lively debate over the short list at the final judging lunch, which necessarily extends well into the afternoon – was again rewarding this year. And I look forward to the annual dinner and lecture at which the winner is announced.

I'm proud that the Lowy Institute makes this Award possible. In its modest way it seeks to nurture the same spirit Moorehead inspired in many young Australians of his time, people like Robert Hughes, Germaine Greer and Clive James.

As McCamish notes in his Moorehead biography: 'Perhaps his most enduring legacy lies in those driven by his example to go out into the world in search of astonishing stories.'