It has been an unusually intense time for elections across Southeast Asia in the past year with both a stunning upset and more predictable returns of incumbents.

But the striking thing from a quick tour of some of the main battlefields is how the general absence of clear policy reform debate in these elections has left a big vacuum for personality politics to fill immediately afterwards.

The idea that Mahathir will become seriously ill before a transition is settled is now a common topic of conversation.

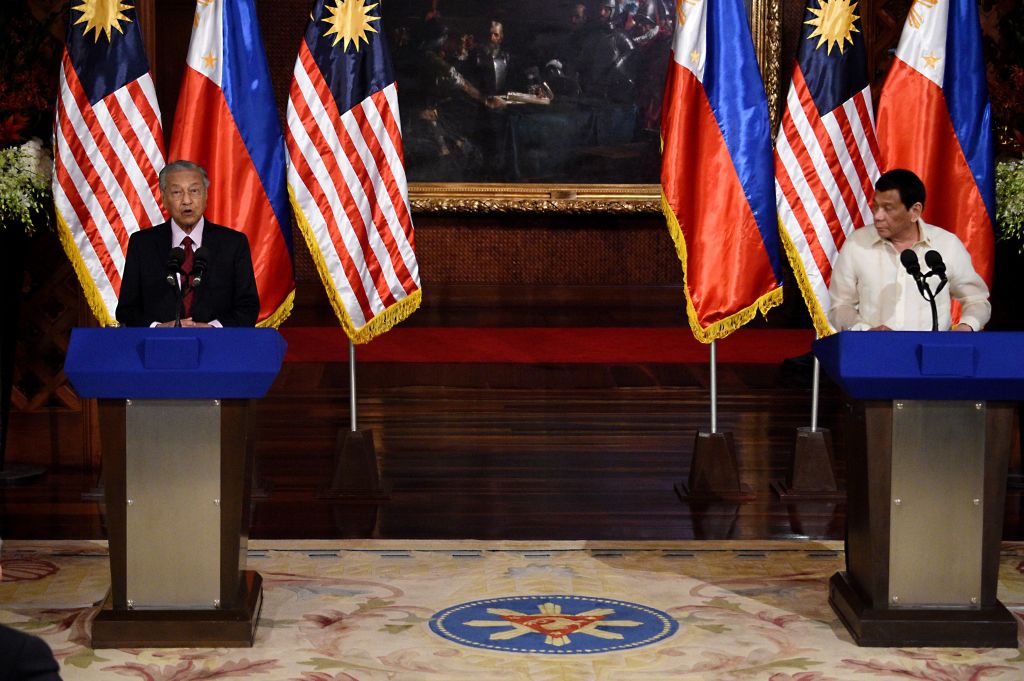

Malaysia was the standout exercise of democracy in May last year, not just because the opposition won but because they did bring the most substantial policy change agenda of the region’s elections.

But a year on one Kuala Lumpur think tank staffer is keeping a record of the number of times the putative next prime minister Anwar Ibrahim says the transfer of power from Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad is going just fine. He says the tally is up to about nine such declarations now and that seems to be a leading indicator that trouble is looming.

The idea that Mahathir will become seriously ill before a transition is settled is now a common topic of conversation. Meanwhile despite coming to power with a decent reform agenda, one observer notes more than a year after the vote: “The government is still working out what it wants to be.” In this situation it is not surprising that the main alternative prime ministerial candidate to Anwar is facing sex scandal allegations.

The government did secure a major promised reform this week by achieving unusual bipartisan support to lower the voting age from 21 to 18. But while this appears to benefit it with more younger voters at the next election, it may actually help the opposition Malay-based parties because older unregistered voters will also be enrolled.

Meanwhile, Mahathir, who turned 94 last week, keeps embracing unfinished legacy business such as reviving Malaysian Airlines amid rumours he is trying to strengthen his support base in the government.

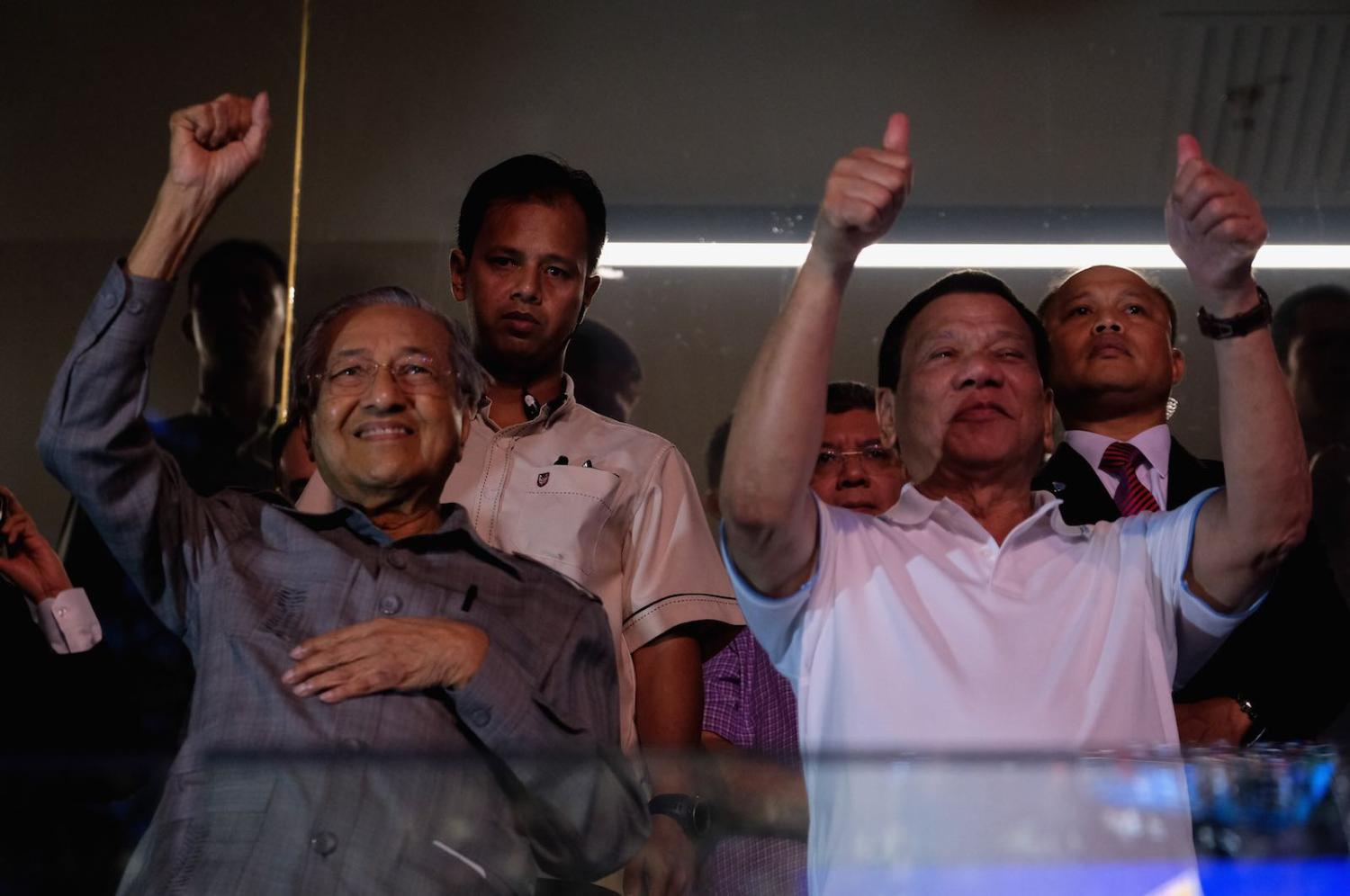

The Philippines is an interesting case given that President Rodrigo Duterte came out of the May legislative elections with a stronger than expected renewed mandate from his various groups of allied candidates. Duterte is notionally in a stronger position than any president since the authoritarian Ferdinand Marcos and has some worthwhile policy reforms to pursue. But he keeps stealing oxygen with his trademark diversionary and usually course antics.

And there is an emerging sense that the team from his landslide election win is fracturing as the country’s political warlords start positioning themselves for the 2022 presidential election, which Duterte cannot contest under current single term rules. He has been forced to split the House of Representatives Speaker job between two men after his preferred candidate and former vice-presidential running mate Alan Cayetano faced opposition from competitors including Duterte’s own son.

Cayetano is now desperately trying to assert himself with a plan to change the terms of national legislators, while Duterte feeds the speculation about being succeeded by his daughter.

This only seems likely to distract attention from his much more ambitious and important plan to shift the country towards a more devolved federal political structure a bit like what happened in Indonesia more than a decade ago.

Meanwhile Thailand finally got a new ministry last week – even though the new parliament was already sitting – after a shameless fight for spoils amongst the sprawling multi-party coalition which Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha was forced to assemble after the election way back in March.

The real success story from the election – the opposition Future Forward Party – had the regional election season’s most compelling policy agenda after Mahathir’s Pakatan Harapan coalition in Malaysia. But even then, Future Forward’s ambitious ideas such as cutting the bloated military budget were curtailed by election campaign time limits and the general crackdown on free speech under the military regime.

As one observer ask: “How can you have discussion about new economic policy or social policy if you have that chilling effect (from free speech limits).”

Singapore’s unexpected economic contraction announced last week only demonstrated the need for the region’s new or renewed governments to be building political and public support for much needed reforms.

Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo appeared to feed the personality politics vacuum at the weekend with his highly orchestrated meeting with his election campaign opponent Prabowo Subianto on Jakarta’s new metro service.

The mobile reconciliation session has left mixed messages about whether a grand coalition is under way which would undermine a proper policy debate in Indonesia or whether Prabowo’s vice presidential running mate Sandiago Uno might take up that role.

But in the context of his regional peers, Widodo deserves credit for keeping valuable policy reform ideas like better vocational training and liberalised foreign investment in the public space in the long interregnum between the May election and the October start to his new presidential administration.

Duterte and Prayut are finally both due to make their post-election state of the nation style speeches in coming days. They will get a chance to demonstrate that there was some policy substance behind the efforts that went into white-anting their opponents by fair and foul means during the elections.

But it seems that we will have to wait until October when Jokowi will formalise the ideas he has been floating in recent interviews and speeches.

He will be kicking off what will be his last term in a significant political career now spanning two cities and national government. It will be his historic chance to inject some real reform rigour and energy into the region like Mahathir started out doing last year.