Outmoded

With the US presidential election sparking all sorts of debate about the future of the erstwhile bastion of global democracy, it is little appreciated what a bad year it has been for old guard forces in the region closer to Australia.

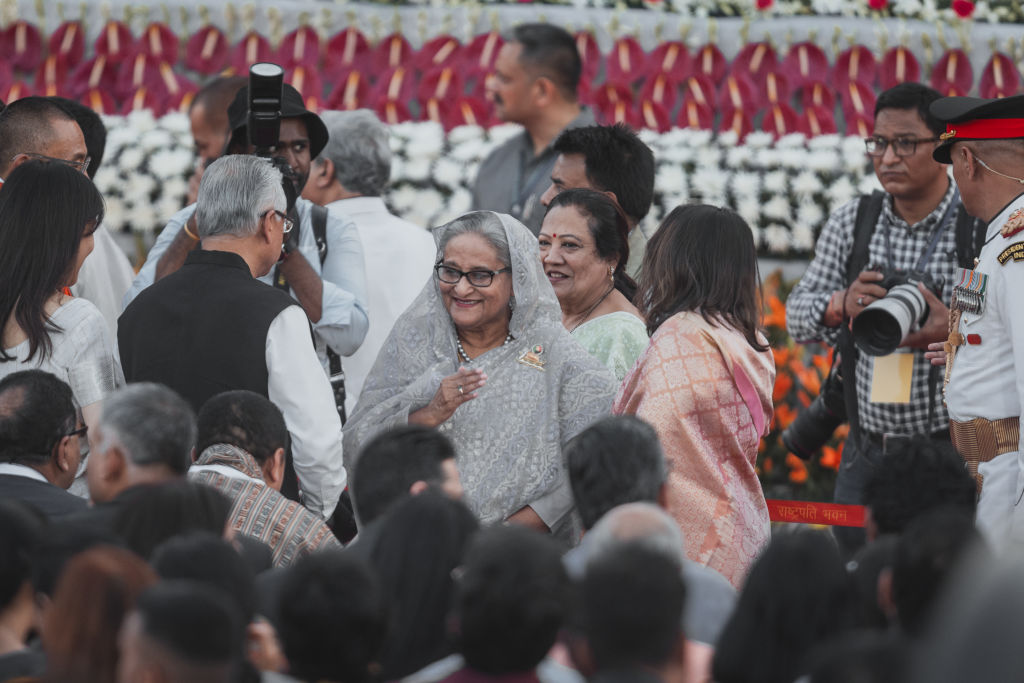

Sheikh Hasina might have scripted yet another victory against a largely non-competing opposition in Bangladesh in January. But the frustration and ill-feeling that this left behind meant she had to abandon the country within seven months.

Candidates associated with ousted jailed prime minister Imran Khan's relatively new Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) ran as independents in February after the party symbol was excluded from voting papers, but still won a third of the seats, embarrassing the army-favoured and once dominant Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz and the Pakistan People’s Party.

In April, South Korean voters made President Yoon Suk-yeol a lame duck in the legislature election with the lowest support for a ruling president’s party in the democracy era.

Despite the growing power of money politics, lingering dynasties, and manipulation of social media during elections, Asian voters have still demonstrated a capacity for turning way from establishment politics.

In perhaps the most important voter backlash of the year in Asia, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi was forced after the release of election results in June to govern in coalition for the first time in more than two decades as a state and federal leader, alongside two regional parties with a history of changing sides.

By September, a once obscure former Marxist Anur Kumara Dissanayake snared the Sri Lankan presidency pushing aside various family-based establishment forces, most notably the Rajapaksas.

And while he doesn’t meet the standard of a scrappy outsider, Indonesia’s new President Prabowo Subianto notably didn’t even mention his predecessor’s pet project of a new national capital in his inauguration speech this month as he focused on other spending priorities.

Minority man

Shigeru Ishiba has sought the Japanese prime ministership about five times now as a man of the people – or at least the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) members rather than the faction chiefs – and a pragmatic reformer.

But after taking the seven decade-old LDP to a snap election within days of winning its leadership in September amid corruption scandals, a breakdown of its faction system, and broader public discontent about cost-of-living issues and political stasis, he is now in danger of becoming the country’s shortest term prime minister.

The slump in support for the LDP and its Komeito coalition partner on Sunday means they hold only 215 seats in the 465 seat Diet, in what is only the third majority loss in the LDP’s history after a brief setback in 1993 and three years in opposition after 2009. Meanwhile the opposition parties combined have a narrow majority, although they have virtually no prospect of being able to assemble a workable government coalition.

Australians could pay a lot more attention to these developments rather than seeing next week’s United States presidential election as the only barometer for the state of global democracy.

That means Ishiba needs to win support from one of the two relatively new right-of-centre parties – the Japan Innovation Party (JIP) and the Democratic Party for the People (DPP). However, they appear reluctant to formally join an LDP government when all the opposition parties are looking towards an upper house election next year to reinforce Sunday’s rejection of LDP dominance.

As a result, Ishiba seems to be gambling that when the Diet meets on 11 November he has more prospect of creating a minority LDP government with periodic policy support from these two parties than either his rival leadership candidates in the LDP or the main opposition party, the left-wing Constitutional Democracy Party (CDP).

Leading from the centre

The LDP, which was formed from the merger of the Liberal and Japan Democrat parties in 1955 as the country’s post-Pacific War recovery took off, has largely functioned as a big tent party accommodating many strands of quasi-conservative thought amid a more splintered opposition over time.

It has really only been rivalled regionally by Malaysia’s United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) as an election winning machine in democratic Asia. And the LDP still remains a much more potent force than UMNO, which has shrunk rapidly in the last few years to become a second-tier party behind the newer centre-left Alliance of Hope of Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim and the Malay nationalist National Alliance of former prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin.

UMNO lost its monopoly on power in 2018 amid persistent corruption scandals, which provides some parallel to the way Japanese voters have turned against the LDP this week.

New Japanese prime ministers often quickly lose support from voters. Instead of turning to the opposition parties, the disappointed voters seem to vote with their feet, with the 53.8 per cent voter turnout this week the third lowest since the LDP was formed. Malaysian voters, on the other hand, have been turning out at around 75-80 per cent amid their country’s party upheaval of the past few years.

The LDP faced a brief challenge in 1993 from new centrist parties amid the economic upheaval from the collapse of the 1980s bubble economy, but quickly recovered.

So, the big question now is how much things have changed.

The official opposition CDP is now newly led by arguably the best of the three prime ministers from the 2009-12 Democratic Party of Japan government in Yoshihiko Noda. Former LDP minister and leadership aspirant turned perennial new party dilettante Yurike Koike has just been re-elected to the powerful platform of Tokyo governor. The populist and idiosyncratic right-wing JIP has been the new party generating the most excitement in the past decade, but this election has raised questions about whether it has appeal beyond its regional base in Osaka.

That leaves the newer centre-right DPP as the pointy end of a change in Japanese politics, with its pragmatic consumer-oriented policies and appeal to younger voters. It had a four-fold increase in its Diet seats to 28 and now faces some hard choices about whether to provide de facto support to a minority LDP government or play a waiting game to have a bigger role in a future government.

Plus ça change?

It is hard to draw a common thread through the backlash against incumbents in many Asian elections this year especially given the possible Japanese parallels with 1993 and the calls from Indonesia’s new president in his inauguration speech for his country to now adopt a “polite democracy” with less bickering.

The outcomes in places such as Malaysia and Thailand after recent experiments with new alternate political forces including respectively the Peoples Justice Party and the Move Forward Party are also far from reassuring about the depth of democratic change.

But despite the growing power of money politics, lingering dynasties, and manipulation of social media during elections, Asian voters have still demonstrated a capacity for turning way from establishment politics.

Australians could pay a lot more attention to these developments rather than seeing next week’s United States presidential election as the only barometer for the state of global democracy.