ASIO Director General Mike Burgess began his 2024 Annual Threat Assessment by heralding the end of business as usual – or “BAU” as he put it.

“If terrorists and spies don’t do BAU, a security service cannot either,” Burgess declared.

He has certainly disrupted the business-as-usual approach with his subsequent revelation during the speech that a former Australian politician, which he did not name, had “sold out their country, party and former colleagues to advance the interests of the foreign regime”.

But the focus since on identifying the politician has obscured Burgess’ broader goals.

Burgess appeared to have several. One is familiar, educating Australians, as he explained, “to ensure potential targets can better recognise, resist and report”.

Burgess then broke new ground by speaking directly to one of ASIO’s adversaries, “the A-team”, which he described in some detail to the audience of senior Canberra public servants gathered at ASIO headquarters:

“a particular team in a particular foreign intelligence service with a particular focus on Australia – we are its priority target. Many of the people here tonight are almost certainly high value targets. The team is aggressive and experienced; its tradecraft is good – but not good enough. ASIO and our partners have been able to map out its activities and identify its members.”

By revealing some of what ASIO knows, Burgess said he was seeking to disrupt the A-team’s work. This was not ASIO’s first attempt, either.

According to Burgess, late last year the A-team’s leader sought to groom an Australian online without realising that the Australian was an ASIO officer. The ASIO officer said: “we know who you are. We know what you are doing. Stop it or there will be further consequences.” Although Burgess went on to invite his audience to imagine the recipients’ “horror”, the threat evidently did not work.

So, Burgess used his speech to take it up a notch. Not only does ASIO want the A-team leader to know that its cover is blown, but:

“we want the A-team’s bosses to know its cover is blown. If the team leader failed to report our conversation to his spymasters, he will now have to explain why he didn’t, along with how ASIO knows so much about his team’s operations and identities … I want the A-team and its masters to understand if they target Australia, ASIO will target them; we will make their jobs as difficult, costly and painful as possible.”

Taking this course of action was far from “BAU”. When intelligence organisations uncover their opponents’ operations, they have a choice. They can either reveal the information to “disrupt”, or conceal that knowledge themselves and seek to make the most of it. Historically, intelligence organisations have preferred to use the information, keeping secret that they have penetrated an operation. There is much that can be done, ranging from limiting the damage through to sending back disinformation in turn. As the John le Carré character Günther Bachmann – brilliantly portrayed by Philip Seymour Hoffman in A Most Wanted Man – put it: “when they’re ours … we direct them at bigger targets. It takes a minnow to catch a barracuda, a barracuda to catch a shark.”

The fact that ASIO has chosen to reveal, rather than use, its knowledge of the A-team tells us two things about the current state of intelligence competition.

The first is that the age-old trade-off between preserving and using intelligence is shifting in favour of use. Burgess says that “while we want the foreign intelligence service to know its cover is blown, we do not want it to unpick how we discovered its activities”. But to achieve the former he’s plainly willing to risk the latter. The United States and United Kingdom similarly sought to operationalise intelligence in the lead-up to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, declassifying and disseminating material with extraordinary speed and breadth.

The shift in favour of operationalising intelligence is driven by both intensifying geopolitical competition and the rapidly evolving information environment. The digital revolution is disrupting “business as usual”, including by breaking down Cold War categories of “secret” and “open-source” information. Secrets have a reduced shelf life.

The second thing Burgess’ speech tells us about current intelligence competition is that ASIO’s knowledge of the A-team’s operations doesn’t give it the edge it once did. Directly confronting the A-team leader didn’t end its operations, and we don’t know whether the latest revelations will do so. It’s possible the A-team will continue with its business.

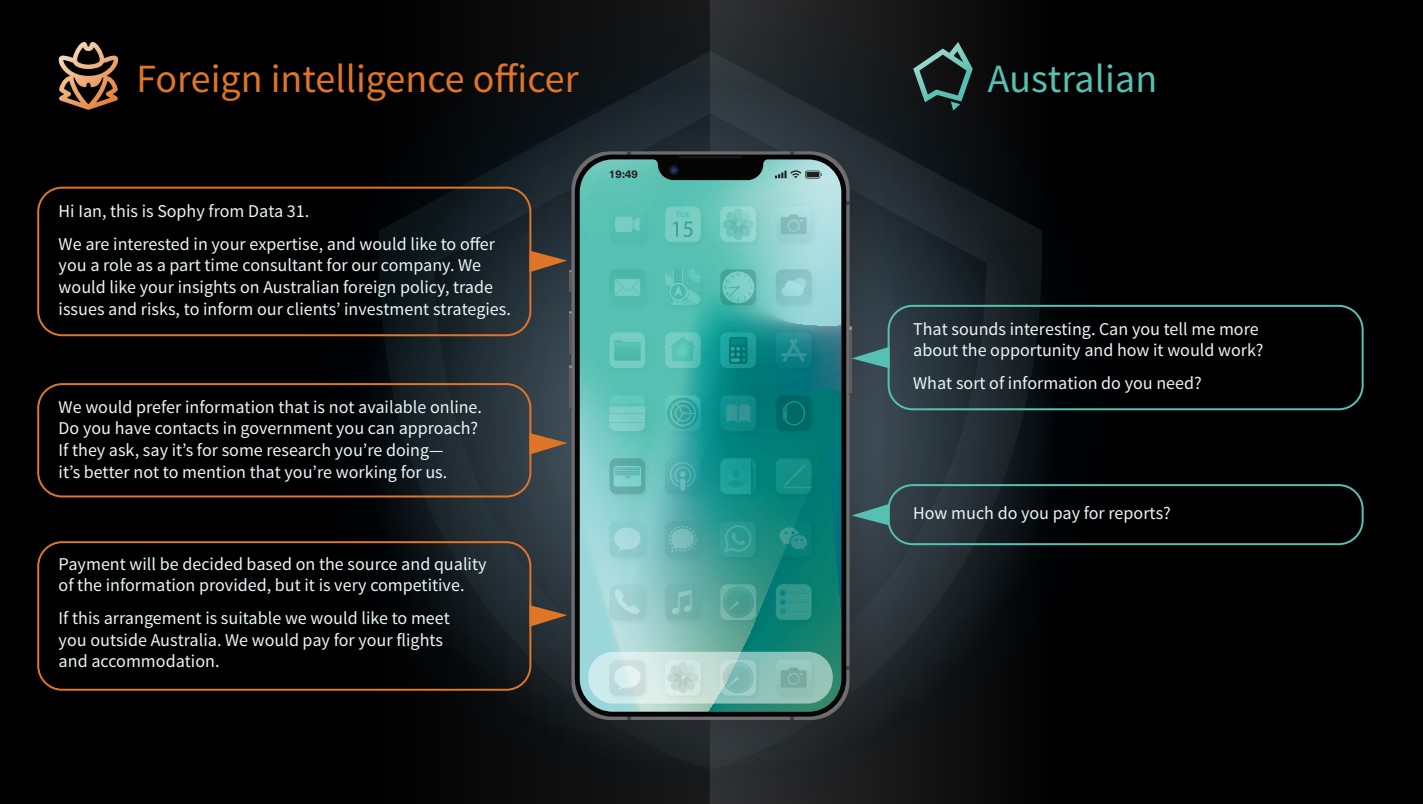

Burgess said the A-team’s “appetites” are wider than just classified material. “This form of espionage is low-cost, low-risk, low-effort – and can be conducted at scale.” Underscoring the point, “Sophy’s” inelegant but successful pitch to “Ian”, which Burgess used to illustrate the threat, would have le Carré turning in his grave.

How should Australia’s National Intelligence Community adapt to this new era? Australia’s intelligence institutions were created during the Cold War to obtain, protect, assess and disseminate secrets. The information revolution is creating a more complex ecosystem, in which information cannot be neatly categorised as public or secret. To break with business as usual, the National Intelligence Community should establish a dedicated open-source intelligence (OSINT) organisation. This would rebalance work in favour of open-source intelligence and produce a more flexible system better suited to contemporary intelligence competition.