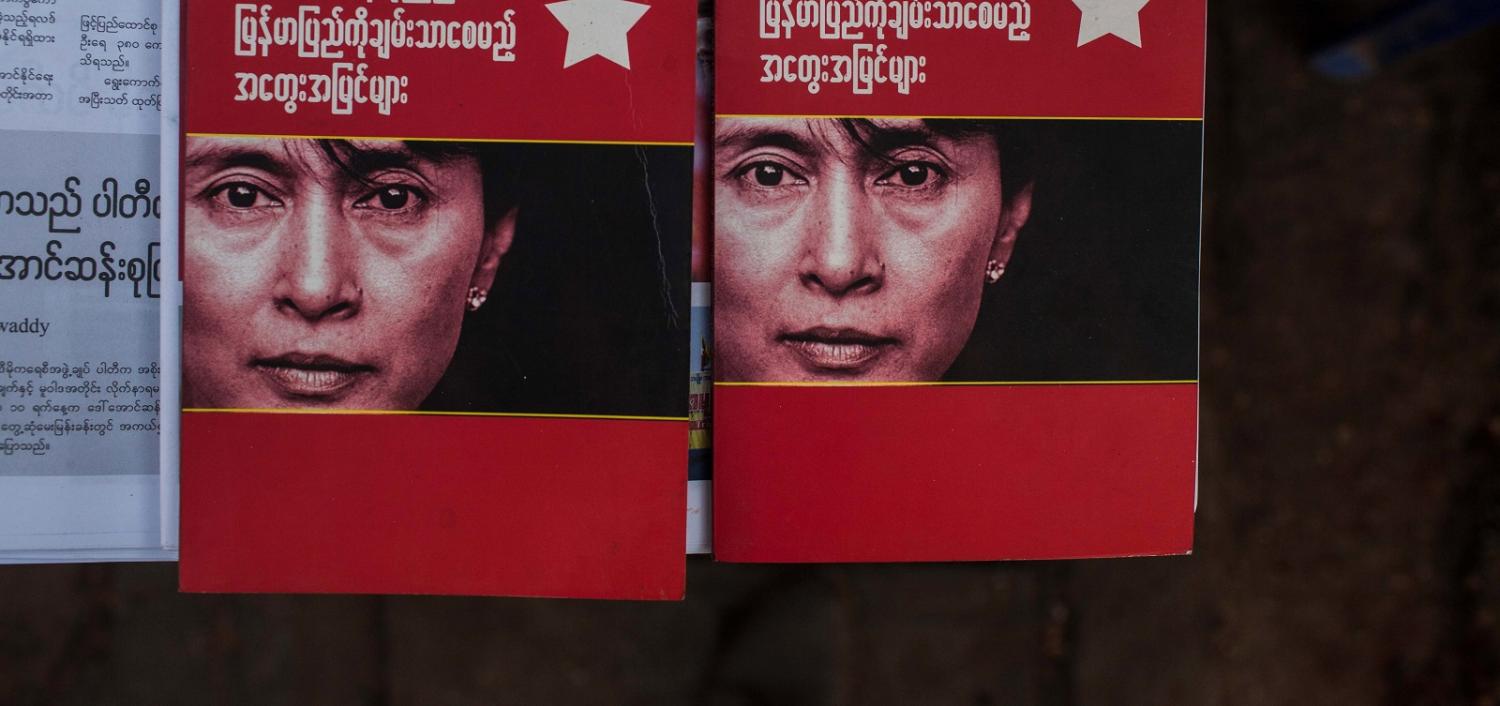

For much of her career, Aung San Suu Kyi has been less a real person than the character in a film script - one with the crudely redemptive arc of a Hollywood blockbuster.

The story goes something like this: the beautiful daughter of an assassinated national hero opposes a gang of tyrannical generals who have driven a beautiful land into poverty and stagnation. Despite being cruelly condemned to house arrest, she becomes a world-famous tribune of democratic values, is garlanded by the Nobel Committee, and inspires a boycott campaign that casts Myanmar out of civilised international company. Eventually, the generals bow to the popular will and announce elections, which Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) wins in an avalanche. 'The Lady' takes her rightful place as Myanmar’s leader, and her people live happily ever after.

To be sure, there are few who really believed things would play out quite so neatly in a nation with such a troubled past. Even so, it is remarkable to note just how far Suu Kyi’s global standing has fallen since she took office as Myanmar’s de facto leader in April 2016. The catalyst has been her unconscionable silence about the terrifying ethnic cleansing now unfolding against the Muslim Rohingya minority in Rakhine State, in western Myanmar.

The latest round of slaughter began after Rohingya militants attacked police stations and a military base on 25 August; the Myanmar security forces have since responded with fury against civilians. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that more than 270,000 people have been driven into Bangladesh. More than a thousand may have been killed. Human Rights Watch has released satellite photos from Rakhine State showing arson on a mass scale.

Like its predecessor, the Myanmar government has argued that 'Rohingya' is an artificial label masking the fact that these people are illegal migrants from Bangladesh. Despite many claiming to have lived in Myanmar for generations, it has refused to give them citizenship, rendering more than a million people effectively stateless. Myanmar army commander Senior General Min Aung Hlaing has chillingly described the government-approved military clearance operations as 'unfinished business' dating back to the Second World War.

It is fair to note that Suu Kyi has not ordered the violence; nor has she effective control of the soldiers carrying it out. Under the junta-drafted 2008 Constitution, Myanmar’s military retains mostly independent of the executive. (This constitution also explains why Suu Kyi was unable to become president, instead holding the title 'state counselor').

Still, she has yet to openly condemn the violence, nor make any attempt to use her massive moral authority among the Myanmar population to alleviate the crisis. And when she has spoken out, it has been to call “fake news” on the claims emerging from Rakhine State. Last week, she reportedly blamed 'terrorists' for the “huge iceberg of misinformation” surrounding the crisis. Meanwhile, her government has restricted access to northern Rakhine State for journalists and aid workers, and accused humanitarian groups of aiding Rohingya militants.

Pundits have struggled to explain the 72-year-old’s silence, arguing variously that it is a result of political calculation, anti-Muslim animus, or her country’s traumatic past. (One factor that has received less attention is Suu Kyi’s simple stubbornness - a trait she showed during her 15 years of house arrest. Armed with an iron will, and perhaps a dash of her father Aung San’s anti-colonial animus, The Lady is not one to be pressured into anything).

Whatever the reason, Suu Kyi’s silence has rapidly depleted her remaining reserves of international moral capital. One British writer has described the Lady of Inya Lake as 'an apologist for genocide, ethnic cleansing, and mass rape'. A Bangladeshi judge wants her to be tried for crimes against humanity. Suu Kyi’s biographer has suggested she retire.

Meanwhile, fellow Nobel laureates have called on her to do something—anything—to avert the crisis. 'If the political price of your ascension to the highest office in Myanmar is your silence,' said Desmond Tutu, 'the price is surely too steep'.

Never has a political angel crashed so quickly to earth. Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991, at the end of the Cold War, Suu Kyi became a personification of the hope, or rather the faith, that the world was somehow getting better.

'The Lady”'so embodied her nation’s interests in the minds of Western policy-makers that her personal approval was seen as necessary for ending Myanmar’s isolation and lifting the final Western sanctions against the country.

Inevitably, the Suu Kyi backlash has given rise to calls that she be stripped of her Nobel Prize and other baubles of international recognition. This is a bad idea. In the first instance, it would be to invest more importance than is warranted in this often dubious and meretricious accolade. In the second, it would do nothing constructive to stop the blood-letting in Rakhine State, and would only deflect attention away from the truly guilty party: Myanmar’s military.

The real lesson we should take from the crumbling of the Suu Kyi myth is to consider how and why we turn leaders into symbols in the first place. As Andrew Selth, a Myanmar expert at the Griffith Asia Institute, put it recently, 'If Suu Kyi had so far to fall, it is because the international community raised her so high'.