Australia recently announced the creation of a $2 billion Southeast Asian Financing Facility to increase trade and investment in the region. While this is a good start, to get the private sector on board with its focus on Southeast Asia, Canberra will have to help businesses overcome a deficit of information about the region’s risks and opportunities. According to a survey of Australian businesses, among their main concerns are political risk, policy stability, and a lack of confidence in dealing with state-owned enterprises, which remain economic gatekeepers in the region, particularly in the priority sectors of energy and infrastructure.

To meet this challenge, Canberra should complement the financing facility by leading the development of a multilateral information facility which would bring together the commercially relevant political and market intelligence assets of the nation’s public and private trade and investment institutions with those of partners that share an interest in increasing Australia’s role in Southeast Asia.

The role of information in emerging markets

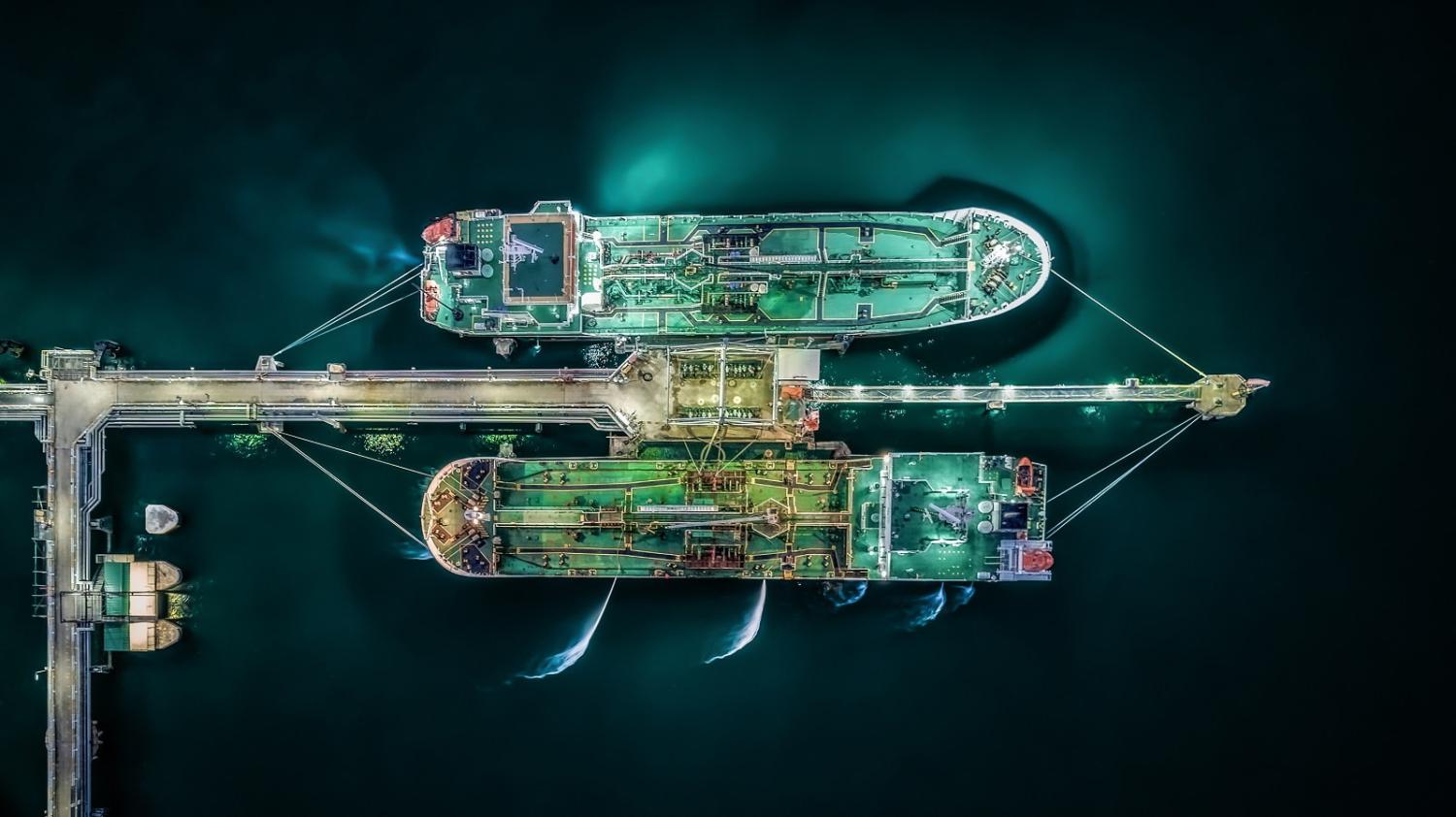

After opportunity costs, a primary reason for Australian underinvestment in Southeast Asia stems from what economists refer to as the “information asymmetry” problem facing businesses looking to engage in emerging markets. That is, local investment counterparts in emerging markets have more information about local opportunities than foreign partners do, particularly where local counterparts are also governmental decision-makers. This increases foreign partners’ perception of risk, driving up capital costs and decreasing trade overall. Economists have found that information asymmetries worsen the greater the share of state ownership in an emerging market. This is particularly relevant in Southeast Asia, where state-owned enterprises continue to play a large role in the infrastructure and energy sectors.

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and private firms have responded to information asymmetry problems by establishing indices that measure the creditworthiness of state-owned entities, bureaucratic transparency and efficiency, political risk, and policy stability. But such indices can be a blunt tool for evaluating risk in infrastructure projects; the success of a high-speed rail line or a power plant may be of great importance to government stakeholders for political reasons. In these situations, the creditworthiness of the SOEs involved may be a poor measure of risk. Instead, paying close attention to the level of political support for a project can be a better measure of project risks.

Export-credit agencies such as Export Finance Australia (EFA) have extensive experience and competencies in assessing and mitigating such project risks, often taking a project-level approach to political risk assessment that integrates country-level risk data with sector and context-specific data. The problem is that EFA has a very limited footprint in the region.

From institutional bricolage to a multilateral information facility

Canberra is already on the right track with the recent creation of Southeast Asian deal teams, which combine the resources of EFA with the broader regional footprints of Austrade and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) to support Australian business and investors pursuing opportunities in the region.

But deal teams are limited in two ways: first, they respond to discrete inquires by those already seeking opportunities rather than proactively improving the supply of information. Relying on existing levels of interest will be insufficient; Canberra must prime the pump that feed the deal pipeline by improving the information environment. Second, deal teams’ intelligence resources are circumscribed by Australian institutions’ limited history of economic engagement across Southeast Asia. This is why Canberra must enlist the participation of Australia’s partners to expand information resources necessary to drive greater investment in the region.

The Trilateral Partnership for Infrastructure Investment in the Indo-Pacific (TIP) brings DFAT and EFA into a partnership with the single largest OECD provider of official infrastructure financing in Southeast Asia, Japan. Yet, as the Lowy Institute’s Lead Economist Roland Rajah has argued, Australia lacks similar collaborative efforts with the second-largest provider of such investment, Europe's development banks, which would bring transaction experience from at least $2 billion in average annual infrastructure development financing in the Indo-Pacific since 2015. Rather than relying on an incomplete bricolage of overlapping initiatives, leading the way on a multilateral informational facility would consolidate available intelligence resources into a single point of reference.

Canberra should also enlist the resources of private sector partners from Australia and its partners. Firms wish to maintain informational advantages relative to one another, but without working cooperatively to improve the information environment, they may all miss out on the opportunities in Southeast Asia. Firms can jointly contribute resources at equal rates in exchange for equal opportunities to benefit from the facility’s global informational base.

Moving forward

Australia must move quickly if it is to accomplish its regional economic and foreign policy goals. Regional rivals already enjoy an enormous head start. A multilateral information facility represents an important opportunity for Australia to lead on a high-value, relatively low-cost initiative that would accelerate its regional foreign and economic policy goals while supporting those of its allies.