On 7 March, Australia and Vietnam elevated their relationship to a comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP), the highest level in Hanoi’s diplomatic classification. This places Australia among Vietnam’s most important economic and security partners, including China, Russia, India, South Korea, the United States and Japan (in order of signing respective agreements). The upgrade is a testament of two like-minded middle powers with a common vision for the Indo-Pacific.

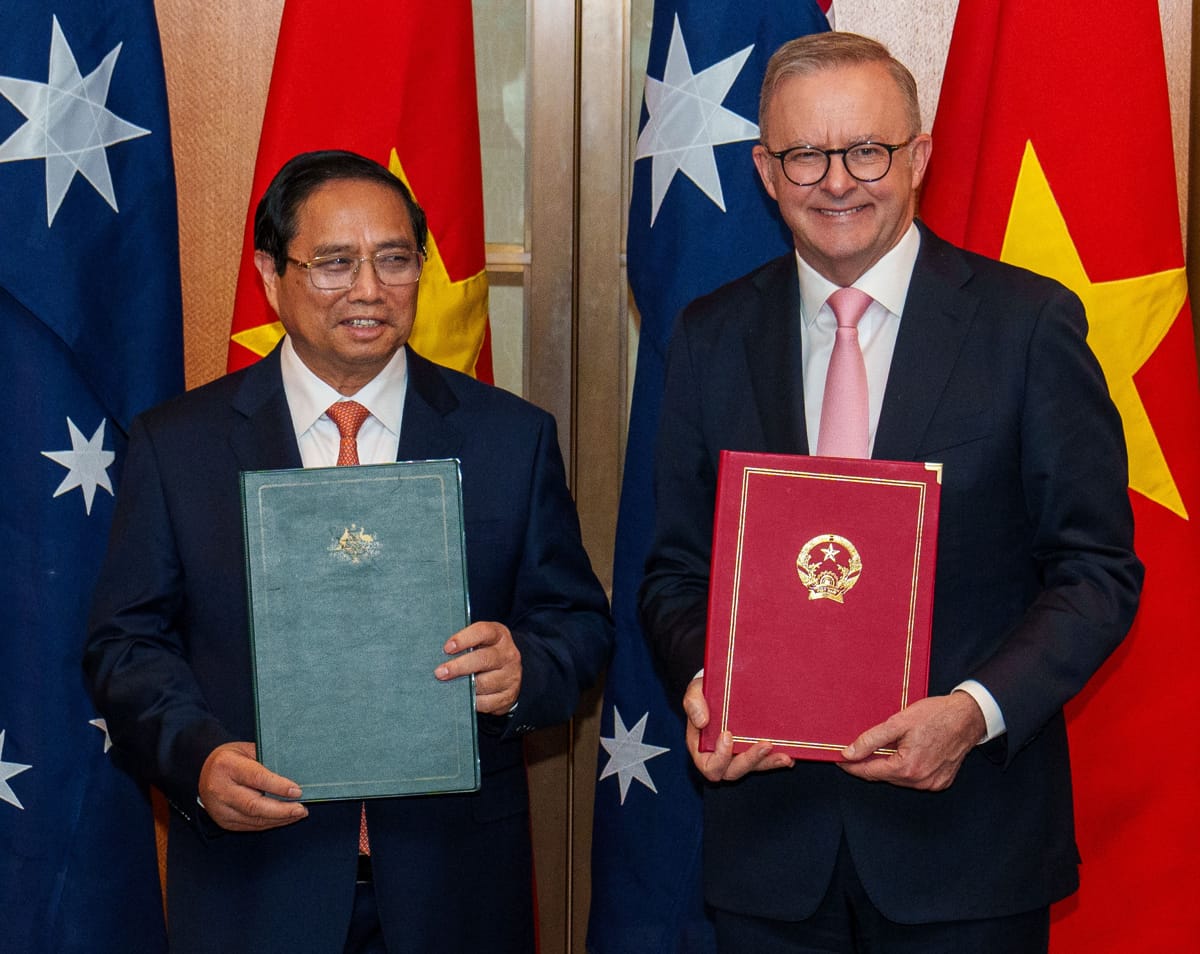

Among the six cooperative areas in the joint statement released following a meeting between Australia’s Anthony Albanese and Vietnam’s Phạm Minh Chính, “Political, Defence Security and Justice Cooperation” is listed first, demonstrating a high level of “strategic trust” between the two nations. Compared to the United States-Vietnam joint statement, defence and security cooperation is listed eighth among ten cooperative areas.

The like-mindedness and middle-power status of Australia and Vietnam explain this connection. Despite differences in ideologies and political systems, the two countries uphold the rules-based order and respect international law, including the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. While Vietnam also shares this view with the United States, power disparity, history, and US intensifying strategic competition with China makes Hanoi uncomfortable moving too close to Washington in terms of security and defence. In contrast, close security and defence cooperation with Australia is less likely to be seen as choosing sides under pressure by a bigger power because Vietnam and Australia are categorised as middle powers, according to the Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index.

Under the CSP, the two countries will further broaden security and defence ties. The two nations have already had strong cooperation in military training. For instance, the Australian government has funded training for around 3500 Vietnamese military officers since 2010. The areas of law enforcement, defence industry, and intelligence sharing will be strengthened, alongside maritime security, which is particularly important to Vietnam given its long coastline and rising tensions in the South China Sea. Since 2020, Australia has helped Vietnam improve its maritime domain awareness through the Marine Resources Initiative and Maritime Consultancy 1.0 and 2.0 programs.

However, trade and investment between Australia and Vietnam has not reached its potential. Despite being part of the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, Australia and Vietnam are not top ten trading partners. In 2022, two-way trade was only $15.7 billion, placing Vietnam as Australia’s twelfth-largest trading partner and Australia as Vietnam’s seventh-largest trading partner.

In terms of investment, the General Statistics Office of Vietnam shows that Australia was the twentieth-largest source of Vietnam’s foreign direct investment in 2022 with 586 projects valued at almost $2 billion, compared to South Korea (another comprehensive strategic partner of Vietnam) with 9543 projects worth more than $81 billion. Meanwhile, Australia is Vietnam’s tenth-largest destination for overseas direct investment with 88 projects at $592 million.

Recognising this, the two countries are committed to strengthened economic cooperation as the second priority area in the joint statement to establish the comprehensive strategic partnership. Under the Australia-Vietnam Enhanced Economic Engagement Strategy adopted in 2021, the two countries had already set an aim to become top ten trading partners and double two-way investment. Both need to take advantage of the three existing free trade agreements in which they are members.

The remaining cooperative priorities of the joint statement are areas of Australia’s strengths and Vietnam’s interests. For example, Australia is committed to supporting Vietnam’s energy transition as a key area of sustainable economic growth, with a $105 million package announced during Albanese’s visit to Hanoi in June 2023. Another important area of cooperation is human resources development. As Vietnam aspires to become fully developed by 2050, high-skilled workers are essential in achieving this goal. With an advanced education system, Australia can help Vietnam improve the quality of its labour force.

The comprehensive strategic partnership is beneficial to both sides. It contributes to Hanoi's principle of diversification in foreign affairs, aiming at avoiding dependence on any single partner or group of partners, and maintaining its strategic autonomy. High levels of cooperation with seven powers helps Vietnam make use of its partners’ resources for its prosperity and security without having to choose sides.

For Australia, the agreement with Vietnam plays an important role in Australia’s Southeast Asia Economic Strategy to 2040, aiming at reducing its economic dependence on China. Vietnam’s strengths include rapid economic growth and a stable political environment. In addition, stronger bilateral relations with Vietnam will help Australia strengthen relations with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations as Vietnam has played a rising role within the bloc with successful terms as ASEAN chair in 2010 and 2020.

To maintain this positive momentum in Australia-Vietnam relations, current and future Australian governments should continue to emphasise the like-mindedness in working with Vietnam, avoiding the dichotomy of democracy versus authoritarianism. By adopting a nuanced and flexible approach, Australia can effectively navigate the complexities of the bilateral relationship.