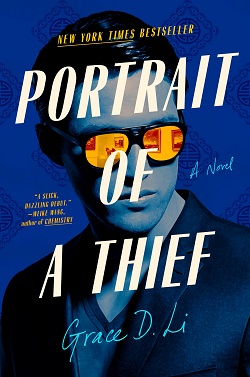

Book review: Portrait of a Thief, by Grace D. Li (Penguin Random House, 2022)

In 1860, the Second Opium War culminated in British and French troops sacking the Old Summer Palace in Beijing. The invading forces looted priceless art and cultural artefacts, which subsequently made their way to museums and private collections across Europe. It is estimated that ten million artefacts were stolen from China during its “century of humiliation”, which dates from the first Opium War (1839–42) through to the Japanese invasion of mainland China (1931–45).

Fast forward to the present and the breakout novel Portrait of a Thief by Stanford medical student Grace D. Li. It tells a tale of fast cars, first-class flights around the world and an ambitious quest to avenge the wrongs of colonialism and China’s “century of humiliation” by stealing back one piece of art at a time from the West.

A fusion of Ocean’s Eleven and Crazy Rich Asians, the book follows five Chinese-American Gen Z characters – the hacker, the thief, the art expert, the getaway driver, and the problem solver – as they plan and execute a series of heists targeting renowned museums across Europe and the United States at the direction of a mysterious Chinese billionaire and the shadowy China Poly Group. Their reward? The chance to get back at the West and take their share of US$50 million.

Fantastical? Maybe. Yet fact is always stranger than fiction. The novel is based on the true story of a series of Chinese art thefts from museums in the West since 2010. In the early 2000s, reaping the success of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, the Chinese government began buying Chinese artefacts from museums and auction houses around the world. With Maoist ideology taking a backseat amid astronomical economic growth, the repatriation of priceless artworks – which the Chinese Communist Party had as recently as the Cultural Revolution designated as symbols of corruption and decadence – became a source of patriotic pride for Beijing and China’s new billionaires.

Yet at the same time, thefts of Chinese art began occurring from museums from Stockholm to Paris. As the heists increased, it became clear there was a campaign targeting artefacts taken by invading forces during the “century of humiliation”. An exposé published in 2018 by GQ magazine detailed the blind eye the Chinese government was turning to the thefts and appeared to hint at the potential involvement of China Poly Group (a real Chinese state-owned enterprise linked to everything from art repatriations and real estate to arms dealing).

Portrait of a Thief imagines the blanks in this story. Yet despite having a century-and-a-half of history and detail to draw on, the book falls flat in parts. The pacing is disjointed and there are too many neat solutions to problems. Some of the prose is repetitive and inclined towards being flowery. And it’s hard to take seriously a heist planned on Zoom and Google Docs. Li’s book also paints a picture of China versus the West, one in which the West is determined to keep China down. It draws out legitimately negative elements of US politics and society, yet glosses over China’s. It would be a more powerful novel if it didn’t.

However, the book’s strength is in its exploration of colonialism, national identity, the experience of the Chinese diaspora, and feelings of belonging. The novel prompts readers to think about the morality associated with the acquisition and custodianship of art and cultural artefacts – and whether it’s okay to steal back stolen art.

The film rights to Portrait of a Thief were snapped up by Netflix before the book was even published – so it’s safe to assume this won’t be the last you hear of this novel.