It’s hard to believe that it’s been almost twenty years since the night of 12 October 2002. The deadly impact of extremism will always be with the survivors and those who lost loved ones in the Bali bombings, and for many the approaching anniversary will be a challenging milestone in an ongoing, unimaginably difficult journey.

I remember only too clearly the call in the middle of the night letting me know, as head of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s consular and crisis management service, that there had been two explosions in the Kuta night club district – a popular hangout for young Australians and other westerners. It was already clear at that moment that many innocent lives had been lost, but it took a little longer for any of us to fully appreciate the scale of the Australian crisis response that would be required.

The attacks were of course a crisis for Indonesia, which lost 38 of its own citizens in the bombings. The attack was a serious blow to Indonesia’s global reputation, revealing the extent to which Jemaah Islamiyah, the Southeast Asian franchise of al-Qaeda, had developed an operational capability and following in the country. For the peace-loving Balinese the incident brought inbound tourism to a sudden halt, inflicting a devastating blow to local livelihoods.

It was a critical national moment for Australia, too. Of the 202 people who were killed that night, 88 were Australian citizens. Some Australian communities, football clubs and families were impacted very heavily by the tragedy. And the targeting of night clubs that were popular with Australians seemed to confirm that we were in the terrorists’ sights. The jihadists’ rhetoric certainly supported this impression: less than a year previously, Osama bin Laden had described our peacekeepers in East Timor as “crusading Australian forces on Indonesia’s shores” whose mission was “to separate … part of the Islamic world”. Australia was declared an enemy in what bin Laden characterised as “a war of annihilation”.

If there was any ambiguity left after the Bali bombings, it was removed by the bombing attack on the Australian embassy in Jakarta in 2004. That slightly arrogant innocence we used to carry around the world with us – that belief that everyone loved Australians – was firmly consigned to the past in those first years of the century.

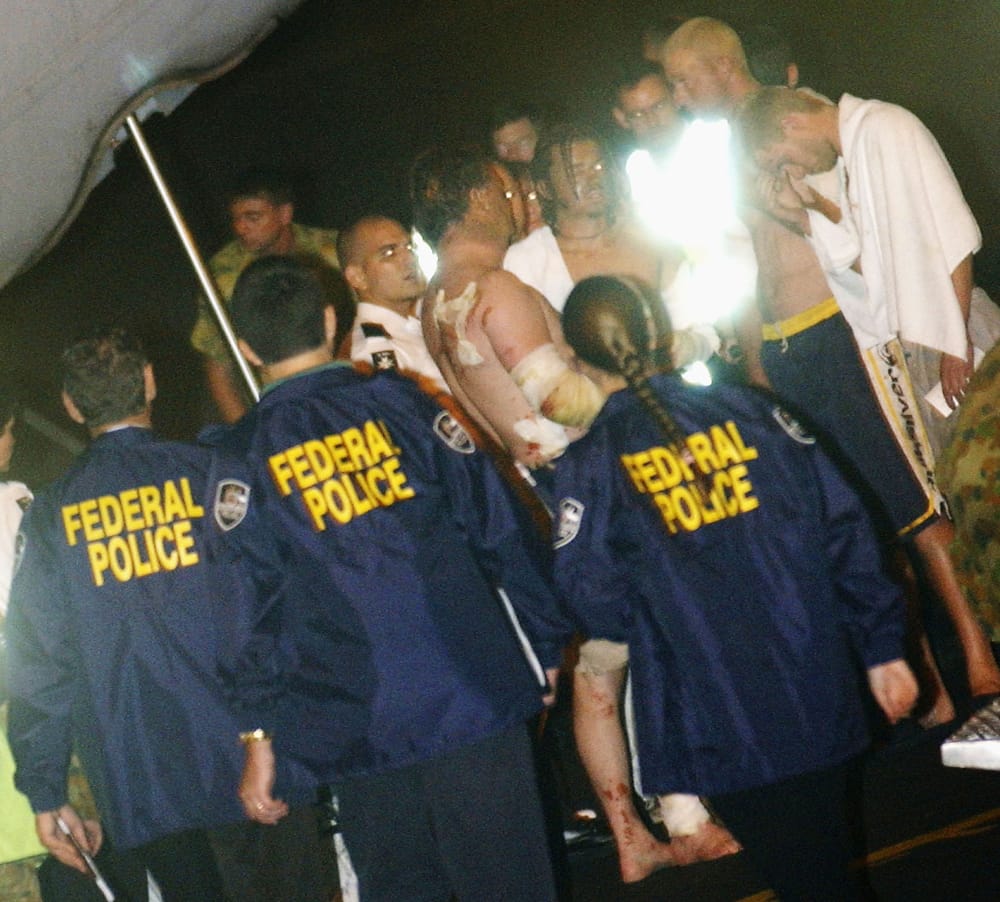

The scale and effectiveness of the Australian response said something about the role that our country can play in the regional neighbourhood. As I recount in my book The Consul, at some point in the early hours of 13 October 2002 it dawned on us that Australia, as the nearest developed country with a quality health system and the resources to manage a large scale aero-medical rescue operation, would have to evacuate everybody requiring medical attention, irrespective of nationality. The Australian Defence Force also evacuated Indonesians from Indonesia – rickshaw drivers, cooks and security guards for whom an emergency flight to Australia was an unimaginable and often terrifying prospect. The Australian Federal Police led and supported the disaster victim identification process that followed, and worked intensely with their Indonesian counterparts to hunt down the killers. Australian hospital staff in Darwin and other capitals were put under great pressure by the sudden influx of serious burns victims and other casualties.

DFAT played the central coordinating role in what was a truly national, long-running and exhausting Australian response. No television mini-series (and one is about to be released) could ever do justice to the work of the Australian volunteers, doctors, nurses, diplomats, police officers, soldiers, officials and many more who were involved. They worked on the sovereign territory of another country to mount a multi-dimensional Australian crisis response that covered emergency medical care, family support and counselling, disaster victim identification and a major criminal investigation. They worked respectfully with their Indonesian counterparts – from the national police to beleaguered local hospital staff and the young Red Cross volunteers who turned up each day to pack ice around unidentified remains at the makeshift morgue.

At the heart of all this were our consular officers – the men and women at DFAT who step forward every day when Australians overseas are confronted with serious welfare concerns, arrest, hospitalisation, or death. It was not their first major crisis. Most were veterans of the September 11 attacks, only 13 months previously, when global jihadism made its unambiguous arrival on the global stage. Many formed the backbone of subsequent crisis operations – the Indian Ocean tsunami, the 2006 Lebanon evacuation, Arab Spring, Fukushima, the downing of MH17 and so on. Their efforts over the decades form the central narrative of The Consul. The experience they developed supported enormous improvements in the service: the pro-active consular network of today has come a long way, and it is underpinned by technological capacities and social media outreach that were once unimaginable.

Over the years, our consular officers have contended with rapidly growing traveller numbers, rising public expectations on the back of the communications revolution, rogue governments playing politics with our citizens’ lives, a pandemic that left many of those abroad desperate to return, and a series of serious conflicts including the current war in Europe.

But above all else, it was the shock of global jihadism that drove the reform and modernisation of the Australian consular service. It led to additional resourcing, further professionalisation and training, the launch of the Smartraveller advisory service, and a more truly whole-of-government approach to crisis management. And the key, crystallising moment that spurred all this reform was 20 years ago, when global terrorism first came close to home.