Beijing must be suffering from a severe case of buyer’s remorse. China’s leaders may speak the language of steadfast “no limits” support to Moscow, yet they are surely preparing for the worst – Putin’s downfall.

However, let us not get ahead of ourselves. Russian leaders have survived and navigated worse times of instability. When it comes to political survival, compromising and clawing are two sides of the same coin – tactics that Russian strongmen are adept at. We were recently reminded of Winston Churchill’s reported statement that Kremlin political intrigues are akin to a “bulldog fight under a rug” and that the only way to know who has survived is when the loser’s bones come flying out.

The last few weeks have been tumultuous in Russia, to say the least. The attempted quasi-rebellion by Yevgeny Prigozhin, the leader of private mercenary organisation the Wagner Group, has unsettled the Kremlin. Observers note that the insurgency was the logical end of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s efforts to cultivate various political factions in Moscow. Playing rival leaders against each other suits his agenda of checking potential power challengers for the top post.

For the last two decades, Putin has deliberately nurtured private mercenaries, the business elite, and military factions to ensure that he remains the final arbiter on all matters. Similarly, Putin created a phantom in Prigozhin to inhibit Russian military generals from growing too big for their boots. Prigozhin’s Wagner mercenaries could also be easily deployed as Russian proxies across borders, limiting the burden on Russian military troops. Privatisation of security had another added advantage – the fact that the Kremlin could disown the Wagner Group’s clandestine activities in Africa and Syria. After all, the goal was to propagate Russian influence and power, whatever the means.

In February 2022, the Kremlin was intoxicated with the dual narrative of the inexorable decline of the West and Russia’s capacity to humble its neighbour. Riding high on the neutralisation of Georgia in 2008, the quick invasion of Crimea in 2014, and the intervention in Syria in 2015, Putin took the risk of barging into Ukraine uninvited. The general assumption in Moscow was that depredations in Iraq and Afghanistan had extinguished Washington’s appetite for conflicts overseas.

With the benefit of hindsight, the last few months have demonstrated the opposite. By not achieving a quick and decisive victory, Putin is already dangerously close to a loss. No power – let alone a great power with a long history – can claim a credible sphere of influence by losing to a neighbour 28 times geographically smaller than itself in its immediate vicinity.

Given Ukraine’s renewed nationalistic resolve and the generous support from its Western allies, Kyiv braved the early onslaught and demonstrated strategic acumen. Kyiv’s defences compelled Moscow to change its strategy from focusing on a quick and decisive victory to fighting a war of attrition. The longer the war lasted, the weaker the Western unity would prove, thought Putin. Putin had faith in the Western public. Sooner or later, he believed, they would begin clamouring for affordable energy and complain about the diversion of economic and military resources. So far, that has not been the case.

From Beijing’s perspective, Putin’s prolonged bungling in Ukraine and internal domestic wrangling – triggered by Prigozhin’s attempted rebellion – is forcing China’s strategic community to ask tough questions about Beijing’s partnership with Moscow. However, given its history and influence, Russia is the only sizable power with a deep disdain for Washington. Therefore, the balance of power logic demands that Beijing make do with Moscow.

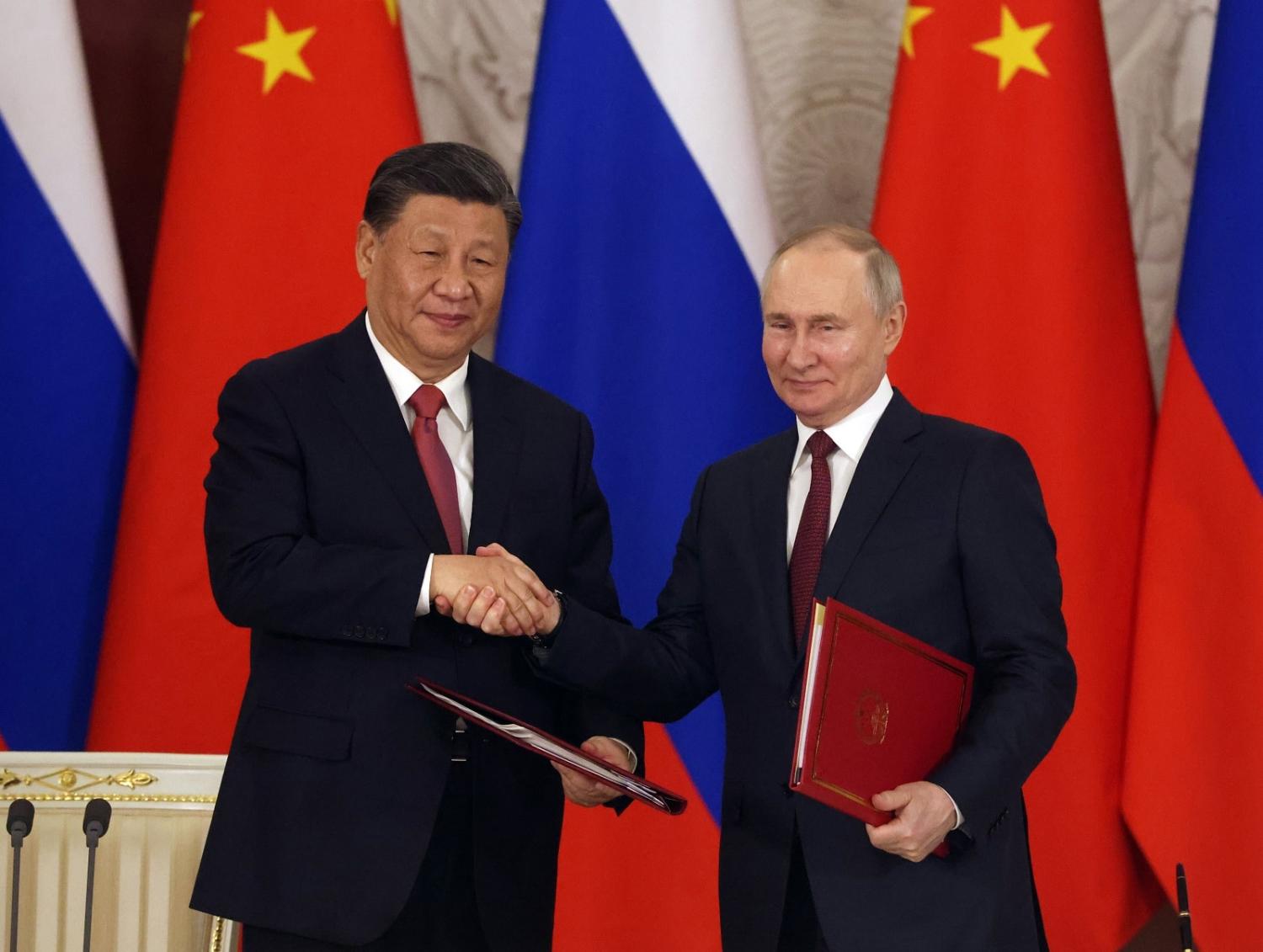

Although the current regime in Moscow is proving to be an unstable partner for Beijing, China’s President Xi Jinping does not have the liberty of choice. Putin is less weak among the other political actors in Moscow. Put simply, Xi has no viable alternatives to Putin to bet his money on, at least for now. Therefore, Beijing is redoubling its rhetorical and material support for Putin and, at the same time, preparing for the worst.

It is also not in China’s interests to see chaos and political instability in Moscow. A weak Kremlin is more subservient and favourable to Chinese influence than a headless Kremlin. The collapse of the Putin regime and a political vacuum in Moscow would mean disaster for Beijing. Moreover, Russia’s humbling in its own backyard would leave the United States free to concentrate on the Indo-Pacific. That is something that the Chinese certainly do not want.