There is periodic hyperbole surrounding the future use of the Southern Ocean krill fishery, often sensationally blaming a future threat from China. Yet krill are in no danger of being overfished. China’s krill take is currently a miniscule portion of catch limit under the present international arrangements.

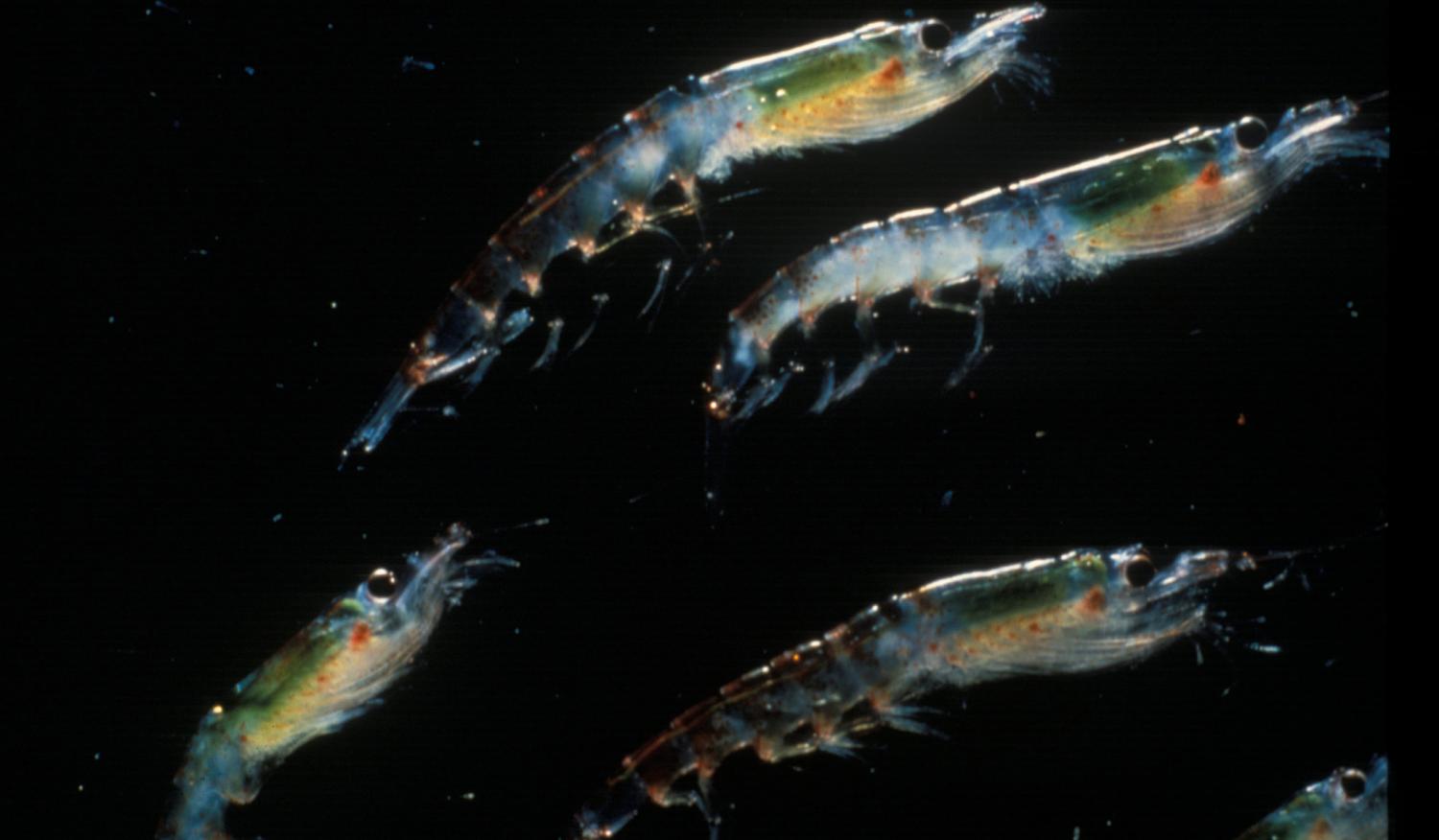

The biomass for Euphausia superba, or the Antarctic krill, has been estimated at around 379,000,000 tonnes for the entire Southern Ocean. Catch limits are managed under the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), and last year was 3,705,000 tonnes, or around 1% of the total. China’s take in 2014, the latest record, was 54,303 tonnes: 1.4% of the catch limit and 0.00014% of the fishery. A fishery this size and this under-utilised anywhere else in the world would not attract any attention for being harvested. So alarmist reports of China planning to increase its krill take need a little perspective.

A good example is the Ross Sea region Maritime Protection Area, first proposed by US and New Zealand, which recently entered into force under CCAMLR. Western media continually frame the Ross Sea region MPA (RSrMPA) as a victory of conservation over China’s krill fishing, however the reality is a little more sober. This MPA means little for the future of industrial krill harvest in the Southern Ocean and also means little for the chances of the future adoption of the East Antarctic MPAs.

Touted as the world’s largest marine reserve, the RSrMPA at first glance seems a significant legal instrument for the protection of marine ecosystems yet in practical terms does little more than current CCAMLR arrangements. Even before the RSrMPA there has been little to no krill fishing in the Ross Sea since 1999, thanks to effective conservation management by CCAMLR. All commercial krill fishing is on the opposite side of the continent, concentrated in the Weddell Sea and Lazarev Sea.

China initially opposed the Ross Sea region MPA over a disagreement between rational-use and zero-take conservation, but under US pressure eventually conceded to the consensus vote required to establish the protected area. China sees the area as fair game for harvesting while conservation-centric countries want to see the whole Ross Sea region as a no-take area. But again, the Ross and Amundsen Seas were already CCAMLR protected areas managed under sustainable use.

Irrational fears still persist though. An oft-repeated line of China planning to increase its Southern Ocean krill take to two million tonnes per season comes back to a single statement made by Liu Shenli in 2015. Liu is chair of state-owned China National Agricultural Development Group and his statement is much better read as domestic policy rhetoric rather than international policy directive. His statement was never supported by the Ministry of Agriculture, which regulates China’s onshore, near shore and distant water fisheries. If Liu’s audience is read as domestic, then it is a cry of paucity, not a threat of strength. China has nowhere near the capacity to increase its take to two million tonnes, and even if it did manage to harvest two million tonnes of krill, this would still be well within the CCAMLR catch limit of around 1% of the total fishery.

China’s distant water fishing operations in the CCAMLR area do pose a problem. The targeting of Patagonian Toothfish and Southern Bluefin Tuna present a far more compelling case of China’s institutionalised illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing. But on krill, China is playing by the rules.

Despite fears of China’s krill fishing, CCAMLR is perfectly capable of regulating the Southern Ocean krill fishery. Norway is still far and away the largest krill harvester, and China has every legal right to access global commons protein, nutraceuticals and genetic resources. The real geo-economic question for marine living resources near Antarctica is genetic resources, and any future international legal arguments will likely centre on rights to access and process these resources in the Southern Ocean.