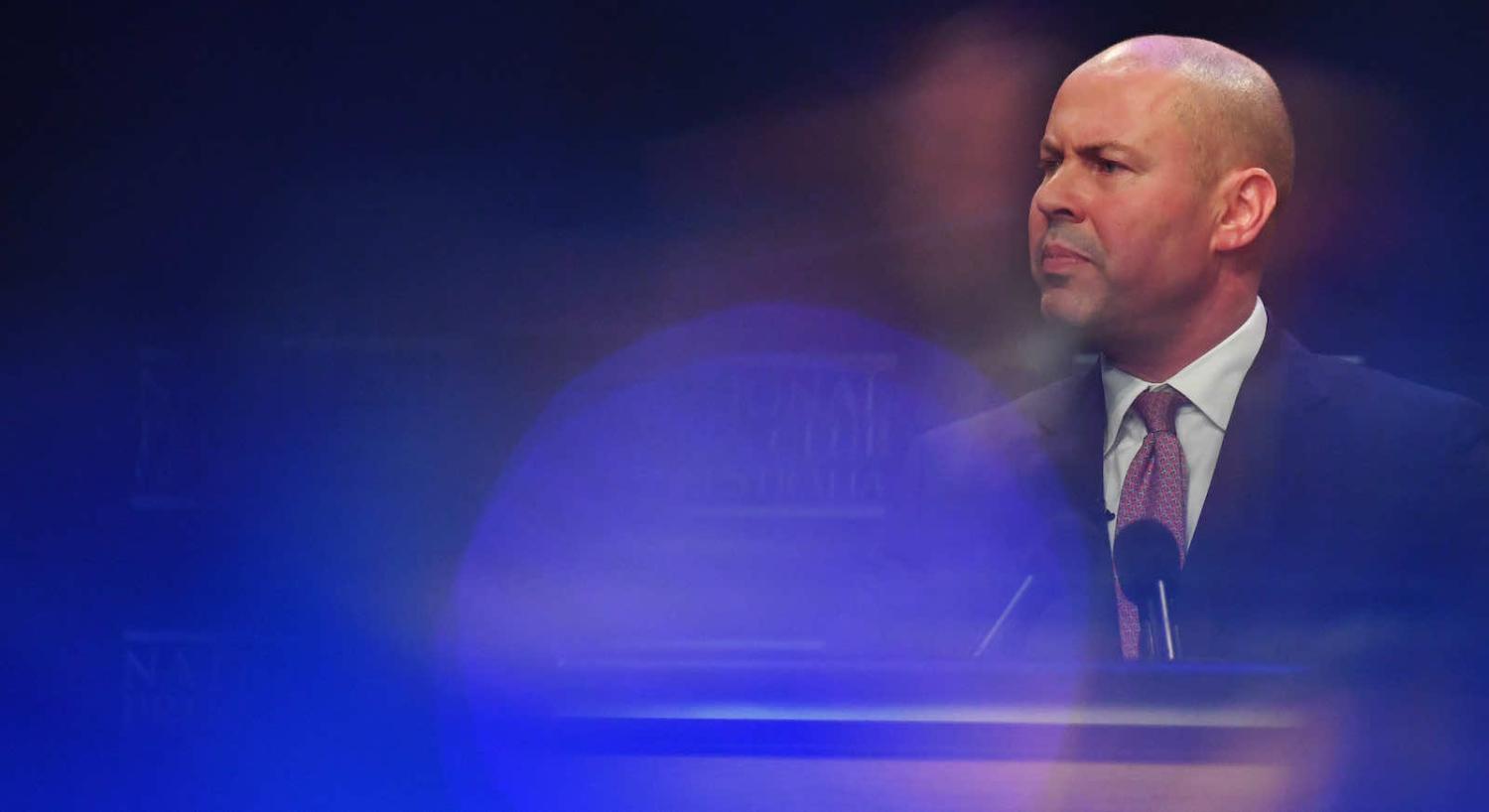

The most important foreign policy speech by a cabinet minister so far this year was delivered last Monday. That Treasurer Josh Frydenberg was the speaker was a little surprising. A little less surprising was that he identified an ascendant, muscular China as a first order threat to the country’s security and prosperity.

The Treasurer’s diagnosis of Australia’s predicament was refreshingly candid, calling out China by name for its coercive diplomacy and manipulation of economic tools.

This is a small but significant progression in Australian foreign policy rhetoric. While the Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, and Trade Minister have all identified “economic coercion” in general terms as a threat to Australia, they’ve stopped short of pointing the finger so directly at Beijing – though the implication was clear enough.

By pointing to China’s “coercive tactics” and its willingness “to use its economic weight as a source of political pressure”, the Treasurer has done something often underestimated: being honest and straightforward with the Australian public about the threats faced.

While restraint is a hallmark of good diplomacy, oftentimes the urge to “maintain good relations” wrongly trumps the paramount duty of our leaders: to transparently explain the nation’s challenges and how the government is managing them.

But beyond the principle of accountable government, why is this so important?

It’s counterproductive to remain ideologically coherent about free trade in an increasingly geo-economic world,

To respond to Chinese economic coercion most effectively, Australia needs the business community on the same page as the government.

In dealing with China, business looks to the government for leadership. Their overriding desire is for a road ahead in the relationship so they can plan and invest.

The second half of the Treasurer’s speech was an attempt to pave that road, pointing to the importance of a resilient economy and a more diverse trade profile.

Not so long ago, “diversify” was a dirty word in Australian foreign policy language. It carried an implicit criticism of China (and those relying too much on that export market) and ran counter to the free trade orthodoxy of many in Canberra for whom market forces alone should determine the direction of trade.

One of Covid’s silver linings has been to explode these conventions.

Starting mid-last year, the Prime Minister and the then Trade and Industry ministers started to qualify Australia’s support for free trade by floating ideas around interrogating supply chains and investing in domestic industries.

The measures the Treasurer explained on Monday are all positive steps in this direction.

Building a more competitive economy, based less on resource extraction, specific trade diversification measures, such as Export Market Development Grants, and enhanced foreign investment and infrastructure protections – all necessary, all important.

While the government should be commended for these steps, a more comprehensive sets of policy shifts is needed.

Foremost, it’s about mindset. Australia needs to get comfortable with having a targeted industrial policy where needed, even if it runs against people’s market instincts. It’s counterproductive to remain ideologically coherent about free trade in an increasingly geo-economic world.

Targeted industrial support and investments from government, investment screening, and stimulating innovation in strategic industries are an undeniable reality. Open economies and free trade and investment must remain the default, but not to the point where it stops Australia taking steps to ensure security and resilience.

The foreign and trade portfolio needs to deal itself more into domestic economic policymaking. Australia should be using its diplomacy to encourage trade and investment with more trustworthy markets and to monitor and manage key supply chains with likeminded nations.

Second, it’s about continuing the plain-speaking with business the Treasurer has initiated. Ministers and officials need to explain the political risks of operating in certain markets – and how trade in specific commodities fits into the bigger geo-strategic picture.

The bread-and-butter work of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Austrade will remain crucial: free trade agreements, breaking down non-tariff barriers, buttressing international trade rules, and providing market intelligence and access to exporters.

But an extra dimension is needed. Both agencies need to work more closely together to provide timely political risk analysis to Australian small and medium-sized enterprises.

For Austrade, this means taking a more strategic approach, integrating advice on political and security risks into their market intelligence for business. And for DFAT, this means being more willing to share frank assessments with those outside government.

Finally, a more systematic examination of vulnerabilities in Australia’s supply chains is needed: a set of tools to classify and mitigate risks.

The Supply Chain Resilience Initiative, which gives businesses grants of up to $2 million address vulnerabilities, is a great start.

And the almost $100 million committed to the Office of Supply Chain Resilience promises to coordinate a whole-of-government approach. However, we’re yet to see any specific policy thinking or initiatives emerge.

If the challenge of economic coercion is as urgent as the Treasurer describes, then there’s no time to wait.