The United Kingdom loves its islands, wherever they might be.

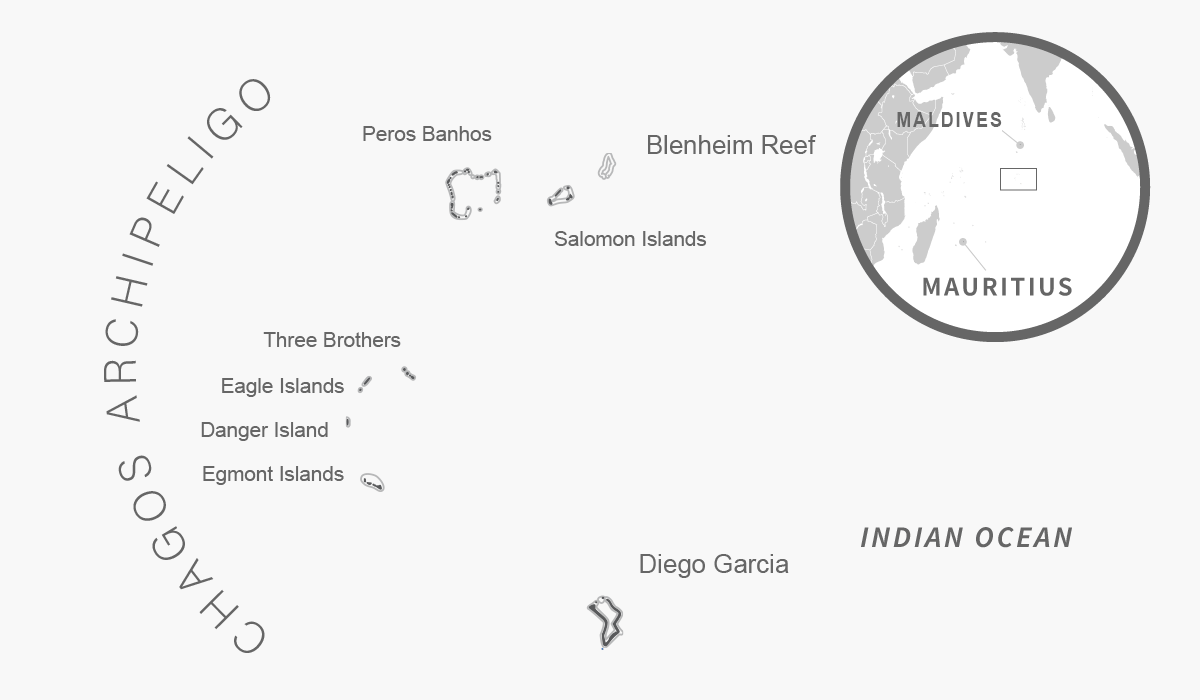

Today, it is continuing a dispute about a set of them in the middle of the Indian Ocean, known as the Chagos Archipelago. Formally the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), the archipelago was administered from Mauritius in the days of empire and was detached in the lead-up to Port Louis’ independence from London in 1968. The Chagos Archipelago contains Diego Garcia, now home to a strategically positioned US military base, whose existence was made possible by the forced deportation of those living there, the Chagossians.

Since their deportation, the Chagossians have been agitating to return to their home. Successive Mauritian governments have also been in negotiations with the UK government and pursuing legal avenues. In 2019, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) handed down an advisory ruling that the United Kingdom had acted unlawfully in creating the BIOT, violating a 1960 United Nations declaration that prohibited the breaking up of colonies before a grant of independence.

This 2019 opinion states that the United Kingdom had no authority to sever the archipelago from Mauritius, and thus control over it should be ceded from London to Port Louis. Despite this ruling, however, the United Kingdom has been reluctant to act on its obligations as laid out by the ICJ.

A key part of these negotiations is the presence of the US base on Diego Garcia, the largest island in the archipelago, which allows surveillance of vast areas of the Indian Ocean and for military aircraft to conduct operations in the Middle East, as they did during America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Growing rivalry with China has intruded in discussions of international law, leading to claims should the Chagos be transferred to Mauritius, Beijing would take advantage to set up a base of its own, or at least secure access to the port facilities and airfield. Former First Sea Lord, the Lord West of Spithead, goes as far as to describe Mauritius as “Chinese-aligned”, citing as his evidence some 47 Chinese aid projects on Diego Garcia.

But this fear rests upon a phenomenal leap in logic. Mauritius does have a strong relationship with China, as many countries around the world do. But if Mauritius is aligned with any country, that country is India, from which the majority of Mauritius’ population trace their ancestry, a product of the British Empire’s practice of importing indentured labourers from India to ensure its sugar plantations continued to function after its abolition of slavery.

And also strong is the modern connection between Mauritius and India. From 2013 to 2021, some $231 million of foreign direct investment came to India from Mauritius, with $151 million going the other way. These same investment flows for China are $89.2 million and $22.5 million, respectively. In total, 3.8 per cent of Mauritius’ trade is with China, compared to 12.2 per cent with India.

India has constructed a military facility on the Mauritian island of Agaléga, which recent reports state is now ready to receive naval and air assets. If anyone would benefit from a new base should Mauritius gain the Chagos, it would in all likelihood be India, not China.

Besides, Mauritius has previously offered to discuss continuing the base operations with the United States for Diego Garcia. It is by no means a given that the US base on Diego Garcia would be made to close if Mauritius gained sovereignty.

The plight of the Chagossians who were forced from their homes in the 1960s is undeniable, but in the negotiations between Port Louis and London, Chagossian voices have been routinely excluded. The issue is also an important one in domestic Mauritian politics, which apart from 2003 to 2005 has had its prime ministers come from two generations of two families. It was Mauritius’ first prime minister, Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, who agreed that the Chagos be separated from Mauritius in 1965 in exchange for compensation – a decision for which he was occasionally accused of betrayal, with some of the money never reaching its intended beneficiaries.

Ramgoolam’s son, Navin, was unseated as prime minister in 2014 by his father’s rival, Anerood Jugnauth, whose son Pravind is now prime minister. The Chagos issue has often been used more as a tool of political one-upmanship by the two families rather than them making any genuine attempts to return a dispossessed people.

Crucially, the current Jugnauth government has stated that “the end of UK administration has no implications for the US military base at Deigo Garcia, which Mauritius is committed to maintaining”. It will allow Chagossians to return only to the other islands in the archipelago.

Two conclusions are evident.

First, current negotiations over the Chagos do not have at their centre the Chagossians themselves, nor even the future of the US base there. It is a highly likely and deeply sad state of affairs that the latter will remain where the former will never be allowed to return.

Second, it is better to avoid what sometimes seems like a reflexive action to assume that all small nations not influenced by the United States must necessarily come under Chinese influence. As the Mauritian case shows, this is as unhelpful as it is incorrect.