Rumors circling about an impending major partnership between China and Iran seem to be accurate. A leaked draft of the agreement published by the New York Times in July indicates that it would involve a deep economic partnership which would open the door for strategic action. Ample speculation about the deal followed the leak. It is fair to say that this agreement would have substantial geopolitical consequences for the Middle East and the Indian Ocean region. All regional actors would suffer political costs, directly or indirectly.

The leaked document details a US$400 billion agreement that will serve as an economic lifeline for Iran, with investments in energy, infrastructure, telecommunications and the tech sector, as well as arms sales. Iran gets a massive injection of capital and a sophisticated development supply chain to invigorate the economy. China gets a guaranteed supply of Iranian natural resources for a premium price for 25 years, and fewer impediments to its own strategic interests.

The financial scale of the reported deal certainly is disproportionate to other regional Chinese investments, but not unusual given China’s pledges for other premier overseas investments. For its part, Iran has denied the truth of the leak and argues that the agreement’s scale is misinterpreted, but conversations within Iran itself suggest the document is valid.

China will promote this partnership as a new part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), but like most of the BRI, the agreement emerged in an ad hoc manner. Beijing saw opportunity in Iran’s international isolation, creating circumstances where Tehran may acquiesce to conditions it would traditionally reject, such as allowing a long-term preferred price for oil and natural gas and Chinese military units and state owned enterprise personnel to be active within strategic areas of the country.

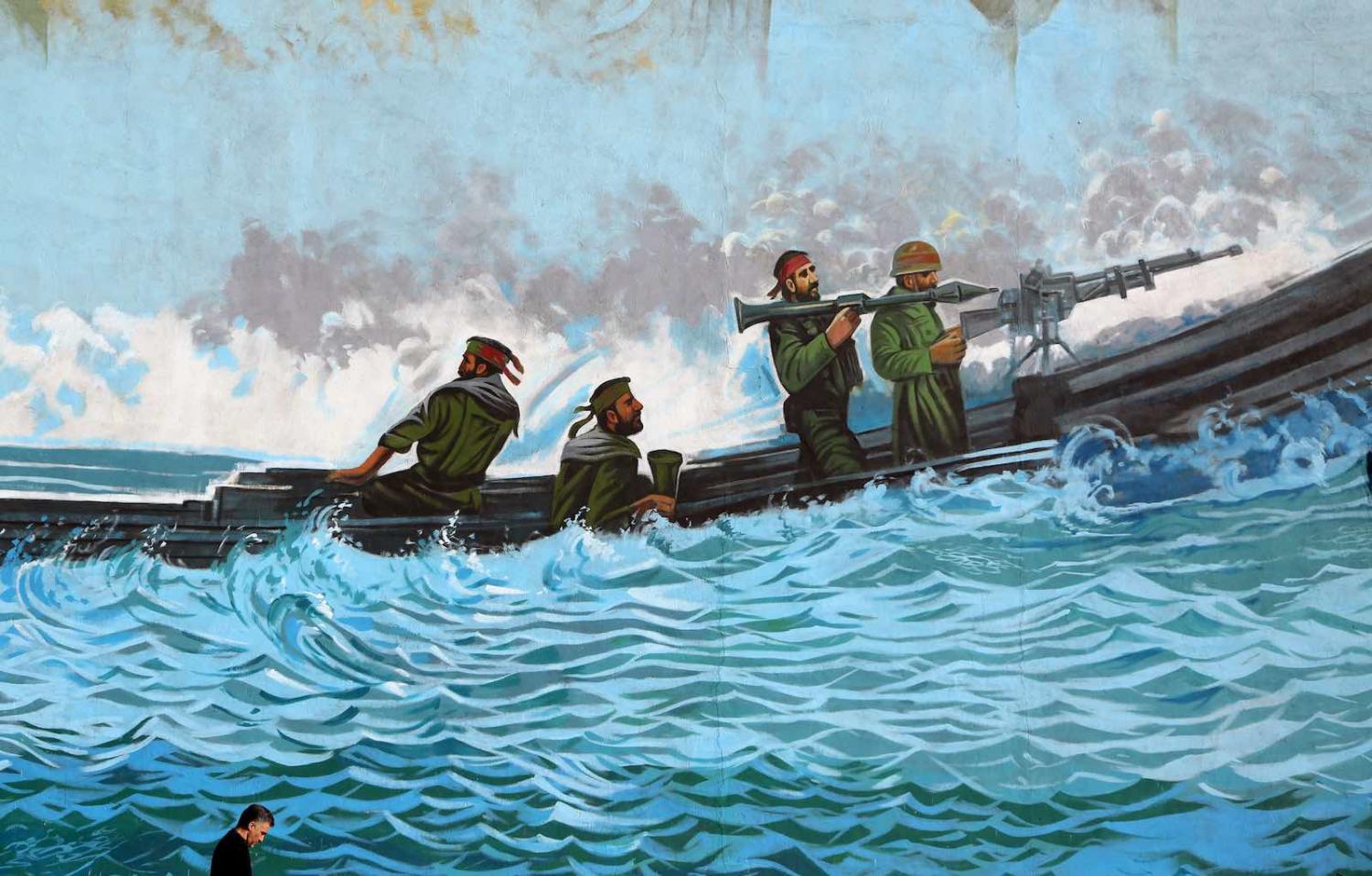

One strategic location mentioned in the document is the Jask port, located just outside the Strait of Hormuz. This would be a focal point of infrastructure development, helping Iran (and China) to bypass the Strait of Hormuz for some energy exports. Upgrading the port could also help further expand Iranian capabilities to threaten access to the Strait.

The agreement could also lend to an increased frequency of bilateral military training and exercises, greater cooperation in weapon systems development, and more frequent information sharing. The detailed nature of the document indicates that increased training and exercises would be highly likely. Weapon systems development is a possible objective in the long-term, but the default starting point would be to expand on previous arms sales. Institutionalised information sharing regarding non-traditional threats is a remote possibility, depending upon progress in the comprehensive relationship.

Beijing is confident that it can navigate the regional political fallout of the deal by reminding countries competing with Iran that they are also major economic partners with China. China has heavily invested in both the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia and positioned itself as a key facilitator of the economic diversification of both countries. China has so far navigated the politics of the Levant well enough to build economic ties with Israel, another key regional actor that would be concerned with any agreement.

Beijing appears to be on the cusp of creating a geopolitical win for itself, but the agreement will also probably create long-term problems for China that are not easily addressed.

For the United States, this agreement provides further evidence of China’s objective to influence the wider Indian Ocean region, encouraging Washington to reshape how it engages with countries in the region. Despite its strategic aspects, China’s narrative of economic partnership and mutual prosperity is not obviously discarded by the Iran agreement, China will paint the US as forcing the region to pick a side between Beijing and Washington. The US will need to be diplomatically adept in communicating its concerns throughout the region.

The costs for India are more immediate. New Delhi’s interests in Chabahar on the Gulf of Oman are not directly impeded, but Iran is frustrated by Indian hesitation to deepen economic ties. New Delhi seeks to avoid international sanctions and moves carefully when vetting investment in Iran. The Chabahar to Zahedan railway project provides insight into both countries’ feelings towards the other. Greater involvement by China in Iran may or may not make India less important, but given recent tensions and Pakistan-China ties, greater coordination with China by Iran would be strategically disadvantageous for India.

Russia, while also a patron of Iran, does not avoid costs. The deal will fuel speculation that Moscow and Beijing will form a partnership to dominate continental Asia. Yet there is no evidence that Beijing coordinated with Moscow on the deal. Vladimir Putin will not be opposed to one of its key partners in the Middle East receiving a lifeline.

But the deal does signal that Russia remains a niche partner and that its comprehensive power is dwarfed by Beijing. Beijing and Moscow may often agree, but this agreement does not signal the imminent arrival of a new Asian axis.

Beijing appears to be on the cusp of creating a geopolitical win for itself. It will have to navigate some regional fears about the agreement, and it will have to address domestic concerns within Iran, but such complications are unlikely to incur major political cost.

The agreement will also probably create long-term problems for China that are not easily addressed. It provides more fuel to the narrative that Beijing seeks global influence according to its own rules. The political nature of the agreement also undermines Beijing’s regional economic messages. It could entangle Beijing in regional politics, in which it has little skill, but something with which its primary geopolitical competitors have ample experience.

Beijing may not have thought through the consequences of the region seeing China as more than a reliable economic partner.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the official policy or position of the NESA Center, the US Department of Defense, or the US government. This article is part of a two-year project being undertaken by the ANU National Security College on the Indian Ocean, with the support of the Australian Department of Defence.