Chinese foreign policy faces an important test in the Middle East.

China’s bilateral trade with the Gulf Cooperation Council and Iran totalled more than $300 billion in 2023, a 48 per cent increase from 2019. China also sources half of its economy-sustaining crude oil imports from the Arabian Gulf. As its economic stake grows, China has taken a more active diplomatic role, notably brokering the March 2023 resumption of ties between Riyadh and Tehran.

However, escalating crises surrounding Israel and Iran along with Red Sea disruptions challenge China's reliability as a partner for Gulf states.

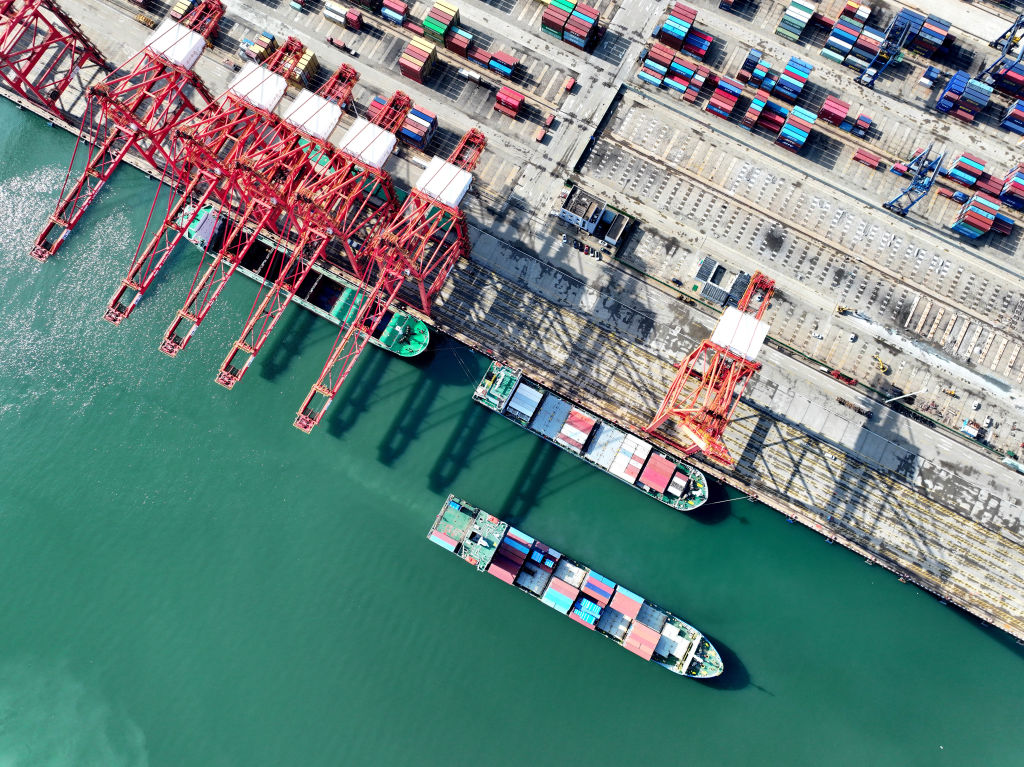

China’s economic interests in the Middle East hinge on its access to the region’s resources and markets, and its ability to transit the Red Sea, especially to European markets.

The surge in Chinese trade with the region is largely due to rising oil prices and, concomitantly, the Middle East’s ability to absorb Chinese exports. In 2023, China exported US$138 billion to the GCC states (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates), Israel, and Iran, while its imports from these economies totalled US$186 billion, according to calculations drawing on China’s trade statistics.

Beijing has far more capacity to exert influence on Tehran.

The trade figures alone don’t capture the full significance. As the world’s largest crude oil importer, China’s supply chains depend on stable access to energy markets. An open conflict between Israel and Iran could trigger an oil price shock, devastating the global economy and disproportionately impacting China, the world's largest exporter and trading nation.

Unlike a potential Israel-Iran direct confrontation, however, the Houthis’ Red Sea attacks are already affecting Chinese economic interests, further disrupting Chinese exports to Europe amid existing trade challenges.

Most obviously, index prices for world container shipping markets have more than tripled from a year ago, compressing Chinese exporters’ margins. Crucially, higher shipping costs affect Chinese exports to all markets, not just those routes that directly transit the Red Sea. Since commercial shippers must divert thousands of kilometres and about 14 days of extra sailing time to Europe due to the Red Sea blockade, international trade – and China’s exports – are being squeezed.

China is aware of its commercial interests and has reportedly pressured Iran to curb the Houthi blockade. But its diplomatic efforts have lacked determination. Beijing and Moscow opportunistically cut deals with the Houthis to allow transit of their vessels – although the agreement has not prevented missile attacks on Russia-to-China shipments, including a recent incident in mid-July. While Beijing does not have unlimited leverage over either Tehran or Moscow, it can do more to solve the multiple crises engulfing the region.

Russia has threatened to extend its involvement in the Red Sea crisis, as Moscow aimed to deliver weapons to the Houthis but withdrew amid pressure from Washington and Riyadh. Still, unconfirmed reports hold that Russian GRU military intelligence officers are on the ground in Yemen.

Beijing can privately urge Moscow not to step up its involvement in the Red Sea crisis, particularly since the entanglement poses escalation risks.

But China is better able to mitigate Gulf instability by insisting that Iran de-escalate in the Red Sea and with Israel.

Beijing has far more capacity to exert influence on Tehran. China is Iran’s largest trading partner, by far. Not only is China the world’s sponge for Iranian crude oil exports, soaking up 90 per cent of all these shipments, but Iran is awash in Chinese imports.

Beijing could privately warn Tehran that Chinese exports to Iran would come under pressure with a further escalation in conflict in the Middle East. A reduction in Chinese imports would accelerate Iran’s inflation, which already stands at an eye-watering 37 per cent.

Perhaps more importantly, Beijing could hint that unconstructive behaviour from Tehran could lead it to unwind purchases of Iranian crude oil. This course of action would be credible. Oil prices have trended downwards in recent months, world spare oil production capacity stands at a historically high 5.8 million barrels per day, and other producers would welcome the opportunity to increase market share at Tehran’s expense.

While Iran is not the only regional actor that must be restrained, its behaviour is increasingly aggressive and destructive. Beijing is uniquely positioned to hold back Tehran. If it fails, the region should take notice.