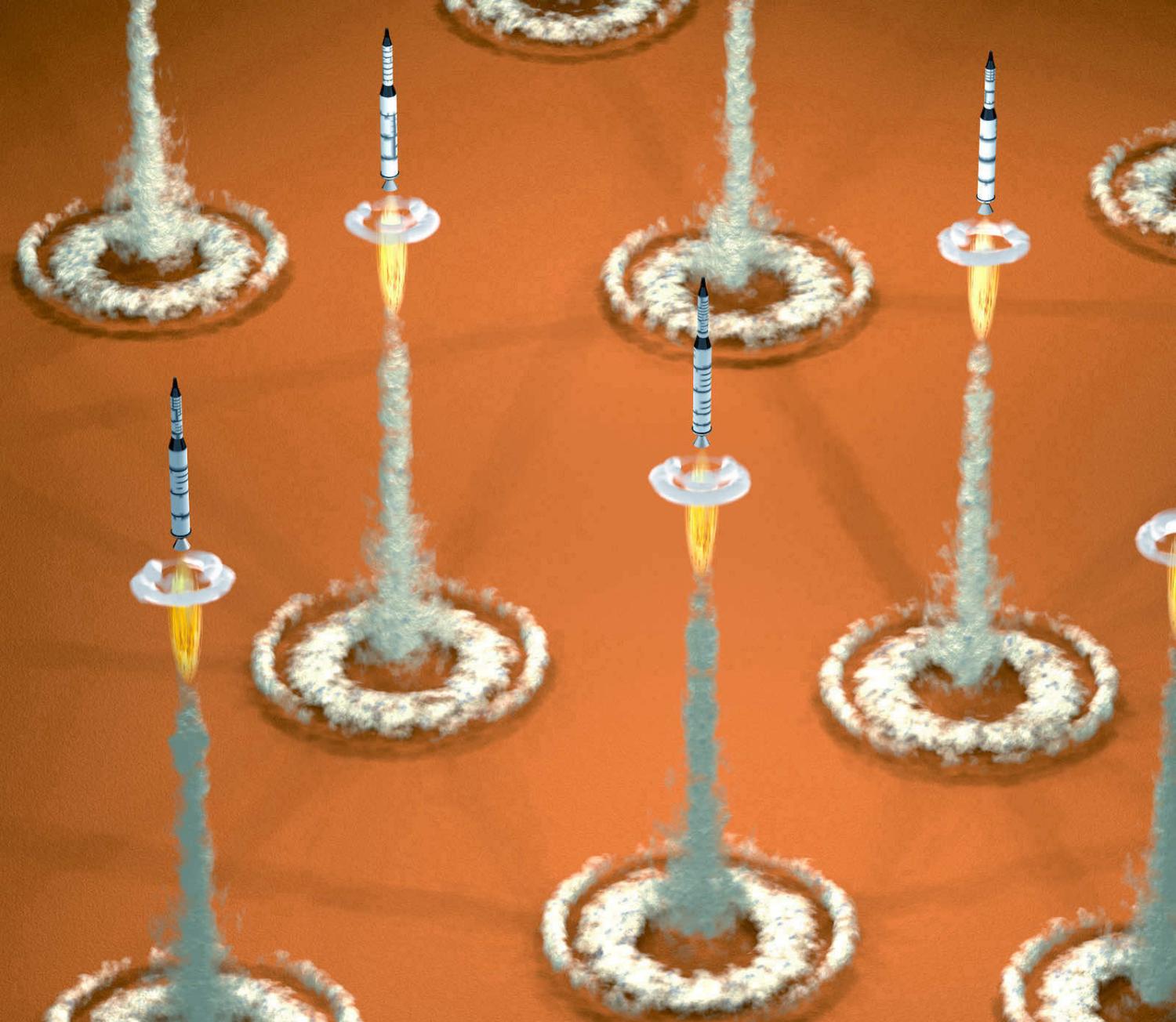

Over the last few weeks, evidence has emerged that China may be expanding its arsenal of nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) on a much larger scale than previously believed. Commercial satellite imagery analysed in June and July showed two huge missile silo fields, each capable of housing up to 120 ICBMs, under construction in the deep interior, in Gansu and Eastern Xinjiang Provinces. And the Pentagon this month reportedly discovered a third field of similar size under construction in Inner Mongolia.

It’s not news that in recent times China’s nuclear weapons arsenal has been growing and modernising, and its delivery systems diversifying. But its stockpile has been seen as still comparatively small, thought to be no more than 350 weapons (with just 100 ICBMs to carry them) as against the 5,600 in the United States’ hands and 6,300 in Russia’s. And these developments, while not comforting, were regarded until now by most analysts as no more than could be expected in a regional environment of growing volatility, not necessarily inconsistent with Beijing’s longstanding “minimal deterrence” and “no first use” nuclear posture.

But the news of the huge new silo fields has certainly set off alarm bells, with the US Strategic Command, for example, referring to “the growing threat the world faces”.

This is the second time in two months the public has discovered what we have been saying all along about the growing threat the world faces and the veil of secrecy that surrounds it.https://t.co/OTFkP14H5o

— US Strategic Command (@US_Stratcom) July 27, 2021

Some of the fears may be misplaced. In particular, it should not be assumed that every new field of 120 silos means 120 new missiles. As the Monterey Institute’s Jeffrey Lewis points out, “it could very easily be 12”. The layout of the silos under construction, spread out across the 1,800 square kilometres or so of each site, closely resembles the planned US “shell game” site of the 1970s, where 23 silos were to be built for every MX missile to shuttle between, with the aim of forcing the Soviet Union to target them all.

And of course it should not be assumed that any new missiles will be acquired for aggressive first use. China may want a much expanded arsenal to give matching status to its new superpower self-image. It may be genuinely concerned about America’s evolving ballistic missile defence capability, and the need for more effective deterrence of new hypersonic and autonomous weapons systems. It may simply be, as New York Times columnists William Broad and David Sanger have put it, “a creative, if costly, negotiating ploy”, creating collateral to be traded away if China is ever persuaded to enter into arms control negotiations with the United States and Russia (very unlikely, but maybe not impossible, as a Stimson Centre analysis out this week interestingly suggests).

It has never been more important for nuclear policymakers everywhere to step back from the brink.

But, even on the most optimistic view, the new developments are troubling. The potential for a full-scale new global nuclear arms race is clearly there. India and Pakistan are increasing their arsenals, as is North Korea with denuclearisation negotiations completely stalled. Even the UK has – extraordinarily – announced a 40 per cent increase in the cap on its own stockpile.

Proliferation pressures are growing in North East Asia, and in the Middle East with the Iran situation still potentially explosive. Major bilateral agreements between the really crucial players, the United States and Russia, are either dead (ABM, INF, Open Skies) or on life support (New START) and it remains hugely uncertain whether the recent Putin-Biden agreement to resume strategic dialogue on these issues will bear fruit.

A major new breakout by China will not help the restoration of sanity on any of these fronts.

It has never been more important for nuclear policymakers everywhere to step back from the brink. True, the risk of deliberate, aggressive use of nuclear weapons by any state may well be no greater than ever, with even the most obdurate leaders well aware that nuclear homicide is likely to mean nuclear suicide.

But the prospect of nuclear catastrophe flowing from system error, human error or miscalculation, now compounded by miscommunication or system breakdown born of cyber-sabotage, and the growing entanglement of nuclear with conventional weapons, is greater than it has ever been. This was reflected by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists placing the hands of its Doomsday Clock at 100 seconds to midnight, closer than ever before. Neither statesmanship nor inherent system integrity explain our escape from disaster so far. Just sheer dumb luck, which cannot be assumed to continue.

The coming into force earlier this year of the UN-negotiated Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons offers some cause for celebration, but not much. It is not going to get buy-in, now or perhaps ever, from any of the nuclear armed states, and those such as Australia who want to believe they gain shelter from their protection. And this for reasons that are not just ideological, geopolitical or psychological, but technical as well: the treaty has real problems when it comes to safeguards, verification and, above all, enforcement.

There is a realistic path forward, and the 2009 report of the Australia-Japan sponsored International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament remains one of the most useful guides to it – I hope a claim justified by more than my co-authorship of it. Like it or not, we have to accept that nuclear disarmament is only ever going to be achievable on an incremental basis, building into the process a series of staging-points. The immediate efforts of activists, and the policymakers they are seeking to influence, should be focused not on elimination but on “minimisation”, or risk reduction.

Priority here should be given to the “4 Ds”.

Doctrine – getting a universal buy-in to No First Use, which is already supported at least notionally by China and India, and a path which President Joe Biden, like Barack Obama before him, would clearly like to go down.

De-alerting – buying time by taking every possible weapon (now some 2,000) off launch-on-warning status.

Deployment – drastically reducing the number of weapons, now around 4,000 globally, actively operational.

Decreased numbers – drastically reducing overall stockpile numbers to around 2,000, down from the more than 13,000 now in existence globally.

A world with much lower numbers of nuclear weapons, with very few of them physically deployed, with practically none of them on high-alert launch status and with every nuclear-armed state visibly committed to never being the first to use them, would still be very far from being perfect. No one should dream of settling for that as the endpoint. But, with the latest wake-up call from China, it is a start the world now increasingly desperately needs.