The enemy of my enemy is not necessarily my friend. Likewise, there may not be an instinctive alignment of my two adversaries.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s reference to “arc of autocracy” and the “instinctive” alignment between Russia and China in the address at the Lowy Institute was a case of this fallacious thinking. It hearkens back to former US president George W. Bush’s “axis of evil” in 2002 and to his slogan that you are either with us or against us. This rhetoric lumped together all the “enemies” of the United States into one bloc.

In this mindset, there are only two sides in the world: us and them, good and evil. The evil ones are working in coordination to undermine us.

The reality is never this simple.

For one, there are usually more than two camps. And they are not rigidly composed. History is replete with cases of shifting alliances. People in the “Western Bloc” tends to remember the Cold War as one between “capitalism” and “communism”. But Communist China and Communist Soviet Union had a huge fallout during the Cold War. Geopolitically, this split was beneficial to the United States, but it was not precipitated by China being less “Communist” or autocratic. Countries do not “instinctively align” just because they have the same ideology.

Just because China and Russia may see the United States and the “West” as a threat, does not mean they support all of each other’s actions.

Other examples of shifting alliances abound, notably between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in the Second World War. At first, they were aligned despite their deep ideological differences, then they turned on each other despite both being autocracies.

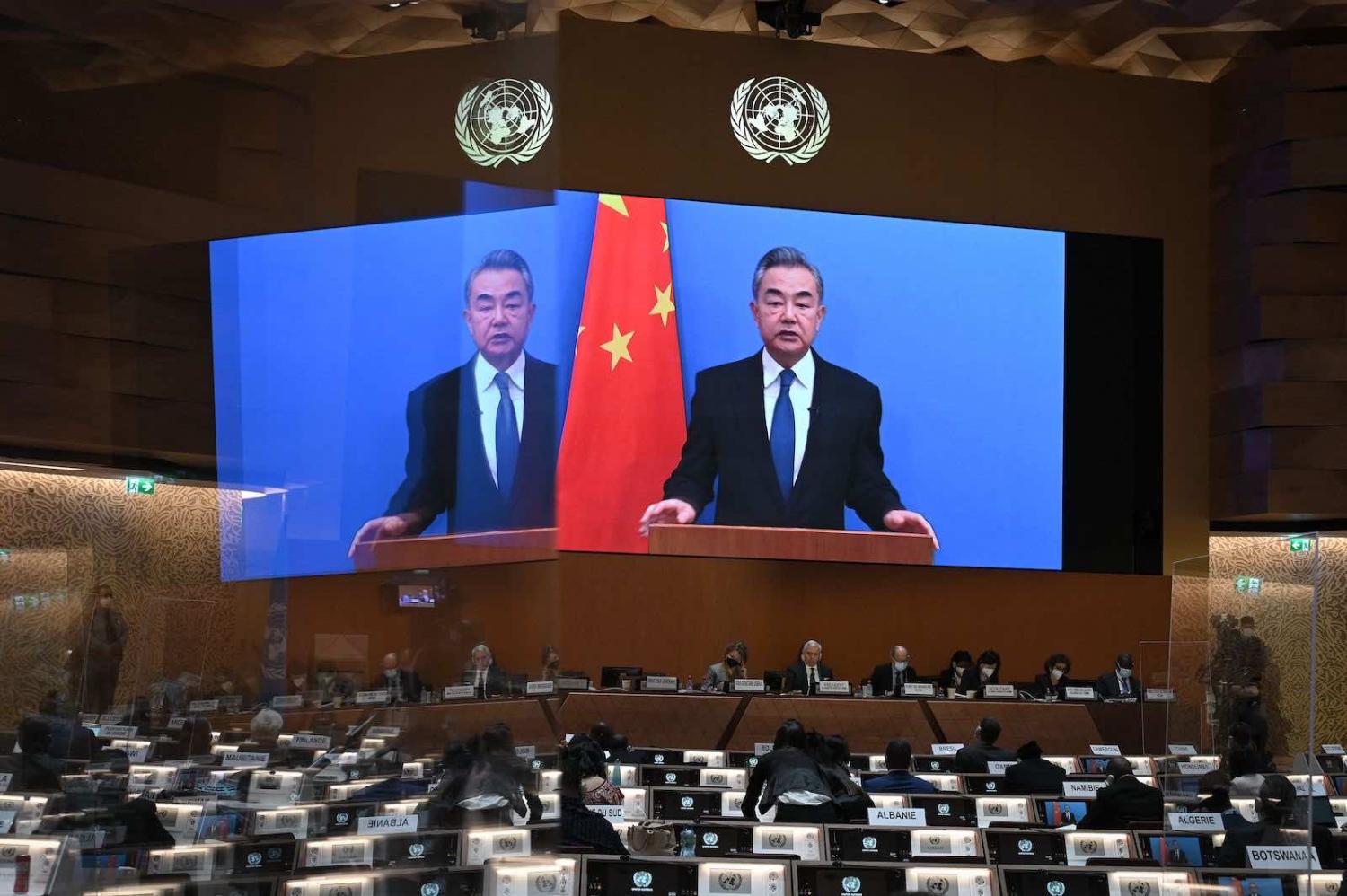

Today, China and Russia have their own national interests. Just because both may see the United States and the “West” as a threat, does not mean they support all of each other’s actions. While China may prefer a more powerful Russia to balance the United States and Europe, it does not necessarily approve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It has walked a very careful line, neither outright supporting nor condemning.

Stability and economic development remain the most important priority for the Chinese Communist Party. Russia’s actions are destabilising and increase uncertainty for China. On the other hand, China does not see benefit in condemning Russia. Such move would do little to lessen the West’s long-term trend of antipathy towards China.

If one relies on a simplistic framework of two camps – autocracies and democracies – one loses the sight of the interests and priorities of different countries. It also raises the question of where to place countries like Saudi Arabia or India.

Saudi Arabia is no doubt an autocratic country, yet it is aligned with the US and Australia sells weapons to the theocracy. India is the world’s largest democracy, yet, like China, has not condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, due to its significant ties with Russia. While Morrison has vocally denounced China for not condemning Russia, he has been remarkably quiet about India’s stance.

Australia’s relationship with India is partly driven by the notion that the enemy of my enemy is my friend. China’s deteriorating relationships with Australia and India has brought these two countries closer than ever. India is a valued partner in the Quad.

However, because of the need to forge a closer relationship with India to counter China, Australia has largely ignored the rising illiberalism and violent Hindu nationalist movements spurred on by India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In recent years, the Indian government has stripped citizenship from mostly Muslim population in Assam and placed them in detention camps as well as intensified repression in the Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir.

Countries regularly ignore human rights and liberal values to cosy up to the enemy of their enemy. During the Cold War, the United States reached out to improve relations with China after the Sino-Soviet split, ignoring the ongoing Cultural Revolution atrocities occurring in China at the time.

Today, those who see China as a serious threat amplify the voices of some anti-CCP dissidents in the United States who supported last year’s attack on the US Capitol. Some dissidents are lionised in the Western media for their opposition to the CCP, even when they are also opposed to liberal democracy.

Of course, sometimes it can be convenient to ally with the enemy of your enemy – and this is probably what China and Russia are doing. They are in a relationship of convenience because they share a common perceived enemy.

However, the nature of such relationships can change quickly. They can have unforeseen consequences – think of the US support of mujahideen in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

These examples show that the “arc of autocracy” and “instinctive alignment” are built on shaky assumptions and may lead to suboptimal policy responses. The government need to move beyond the simplistic binary framing when communicating its foreign policy to the Australian public and the world.