When we think of the renewable energy transition, we don’t typically associate it with inequality, human rights violations, and environmental destruction.

Yet the reality is, as the world shifts at pace to renewable energy, pressure is ramping up on a finite set of critical minerals needed to power renewable energy, and with that comes the potential for abuse.

Critical minerals, such as copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt, and other lesser known rare earth elements, are essential for a renewable energy future. They are key inputs for solar panels, wind turbines, EVs and batteries. As we switch to renewable energy, pressure on these critical minerals is only going to ramp up. To achieve net zero emissions by 2050, the International Energy Agency estimates that demand for critical minerals will increase three-and-a-half times by 2030.

But as the UN Secretary-General António Guterres has noted:

“Too often, production of these minerals leaves a toxic cloud in its wake: pollution; wounded communities, childhoods lost to labour and sometimes dying in their work. And developing countries and communities have not reaped the benefits of their production and trade.”

In an effort to bring focus and attention to this issue, in April Guterres established a Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals. The Panel will be co-chaired by South African ambassador Nozipho Joyce Mxakato-Diseko and European Commission Director-General for Energy Ditte Juul Jørgensen. Members include government actors from 25 countries and 14 non-state actors.

The panel has been given five areas of focus: equity, transparency, investment, sustainability, and human rights, and developing a set of global, voluntary principles to safeguard environmental and social standards and embed justice in the energy transition.

“We cannot replace one dirty, exploitative, extractive industry with another dirty, exploitative, extractive industry.” – UN Secretary General António Guterres

Two key issues arise with critical minerals: social and environmental harms to local communities, and the globally unequal distribution of benefits.

Rare Earth Elements (REEs) sourced from Kachin State, Myanmar, are just one example of why the work of this UN Panel is important. REEs are essential to make permanent magnets, which are used in wind turbines and electric vehicles. But behind the promise of renewable energy lies a troubling reality. In Kachin State, all REE mining is illegal, but backdoor deals are being made with businesspeople in neighbouring China and armed groups to set up these mines. In some cases, land has been forcibly taken by militias, and child labour is being used in the mines. There is also evidence that profits are being used to fund armed groups.

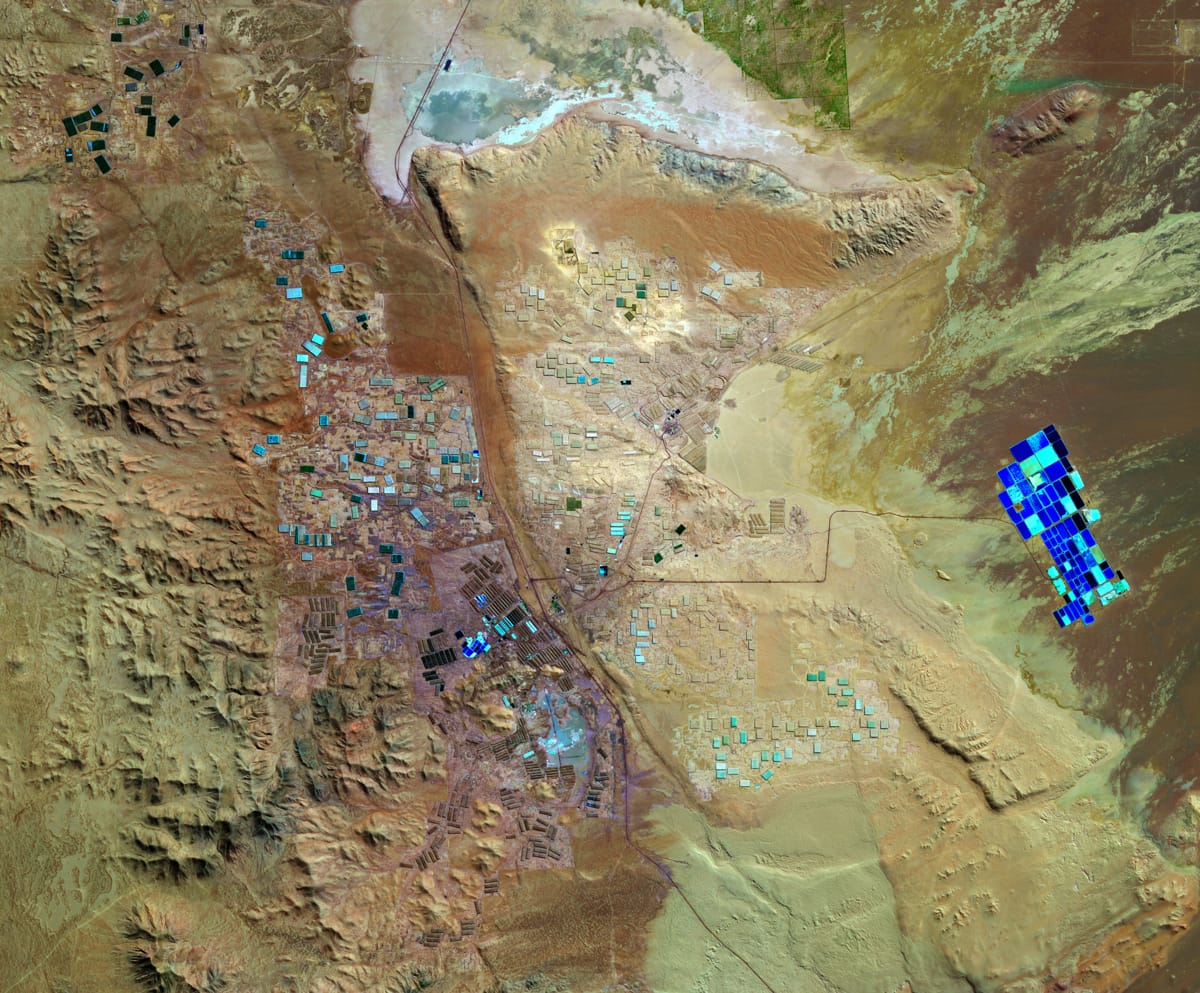

In March 2022, satellite technology showed 2700 illegal mining collection pools. Once REEs are extracted, the polluted sites are abandoned, leaving toxic chemicals to leak into the waterways. This in turn destroys ecosystems and agricultural livelihoods.

While China once dominated global REE mining, the government’s efforts to clean up the industry drove Chinese investment over the border, to REE mining in Myanmar. State-owned Chinese companies control about 80 per cent of global rare earth refining. All REEs mined in Kachin are exported to China for processing into magnets, which are sold on global markets.

We need to take a long hard look at what can be done to prevent social and environmental harms and ensure equitable distribution of benefits.

International standards on business and human rights already exist in the UN Guiding Principles of Business and Human Rights, and the OECD Guidelines on Due Diligence has recently been extended to cover both environmental and human rights obligations.

This year, European legislators passed the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). The law is based on the premise of “do no harm” and to remediate harm that has already been done. Entities operating in Europe must identify “adverse human rights and environmental impacts in their chain of activities”. Importantly, entities must also act upon their assessment by preventing and addressing adverse impacts, assessing the effectiveness of their actions, communicating to the wider community, and providing remediation where necessary.

Backed by the power of a €14.5 trillion market, the European CSDDD is expected to drive a seismic shift in business efforts to prevent risks to people and the planet. But other markets are yet to follow. Australia, for example, has yet to even consider introducing a national law to comprehensively protect human rights, let alone having extended these obligations to business.

What about obligations on government and business to go beyond “do no harm” and instead require them to actually create value locally in the countries where critical minerals are being sourced?

National-level legal mechanisms have been put in place, but their success is limited. South Africa leads the world in platinum production, a metal essential for making electrolysers for green hydrogen. Companies seeking mining rights here must submit a legally binding social and labour plan, detailing how mining benefits will be shared with the local community. Unfortunately, research reveals that some companies fail to fulfil their commitments, leading to a decline in community well-being. This problem stems from poorly designed plans, non-compliance by mining companies, and inadequate oversight by state regulators.

In this light, we fully support the UN Secretary-General’s stance that “we cannot replace one dirty, exploitative, extractive industry with another dirty, exploitative, extractive industry”. This is where the panel needs to think expansively and act urgently to avoid the failures of the past.