From the first days in January this year, the question that dominated the outbreak was how upfront Beijing had been about the novel coronavirus that became known as Covid-19. Richard McGregor:

So far, the handling of the crisis seems to have underlined one of the ongoing problems with the authoritarian strictures of the party-state, which places a premium on the control of information in the name of maintaining stability … Could the virus have been contained, and its spread limited, if officials in Wuhan had levelled with both their bosses, and the public, earlier? It is impossible to say, but at the moment, it certainly looks that way.

Still, the warning signs about the rapid spread of the virus – and what would result in more than 1.7 million deaths so far – did not translate into public trust, particularly in already politically stressed Hong Kong. Vivienne Chow:

An unprecedented level of panic is caused not just by fear, but by the lack of trust. Reactions of the people of Hong Kong and the international community are a vote of no confidence in the authorities’ abilities to protect people and contain the virus. Authorities here are not only the Hong Kong and the Chinese governments, but also the World Health Organisation, which is supposed to “lead partners in global health responses”.

Australia began to react with travel restrictions, buying time at a cost to the education and tourist industries, but Dominic Meagher warned “that time must now be used effectively”.

Three things must be done: eliminate panic, develop some form of treatment, vaccine, or cure, and put in place more sustainable policies to slow down the virus.

But by late February politics and prejudice had complicated the response around the world over. Audrey Jiajia Li:

With 28 countries so far reporting confirmed cases of the virus, caution over the mysterious deadly illness is expected and natural. Yet it is important to emphasise that Chinese people are the victims, not the culprits, of this epidemic.

South Korea, Europe, the United States, India and almost everywhere saw spiking rates of infection. The Tokyo Olympics were soon abandoned, Indonesia struggled and Pacific island nations feared the danger as lockdowns spread. Leaders felt the pressure to rise to the occasion. Michael Fullilove:

There has been a lot of discussion about the communications tools, including websites and texts, that governments are employing to speak with their nations about the coronavirus pandemic … The media noise being generated about Covid-19 is deafening – but the single note of a good speech, well delivered, can penetrate it.

And by the end of March, it was increasingly clear the virus would hold momentous consequences for the world. Daniel Flitton.

The crisis will affect everything in some way, whether budget assumptions, global supply chains, or the trappings of power … drastic change [may be] later assimilated into a “new normal”, the point was still a major readjustment and far-reaching – and lasting – implications not only for the community, but also for relations between nations.

So The Interpreter examined the cross-cutting influence of the virus had on existing international challenges, whether the Hong Kong protest movement, poverty in India or the Philippines, migrant workers in Singapore, insurgency in Thailand, fighting the remnants of Islamic State, conflict in Afghanistan or tensions on the Korean peninsula. The crisis had a disproportionate impact on women, while the cost to the global economy was also manifesting. Roland Rajah:

The social distancing required to slow the virus – both voluntary and mandated by governments – means the economic hit is going to be large, and there’s probably not much that traditional demand-stimulus policies can do to materially counter it. In part, that’s because people won’t go out to spend the money, but it’s also because the virus is an intensifying supply-side shock as well – with big disruptions to normal business activity and many workers pulled out of work, either for health reasons or as workplaces and schools are temporarily shut down.

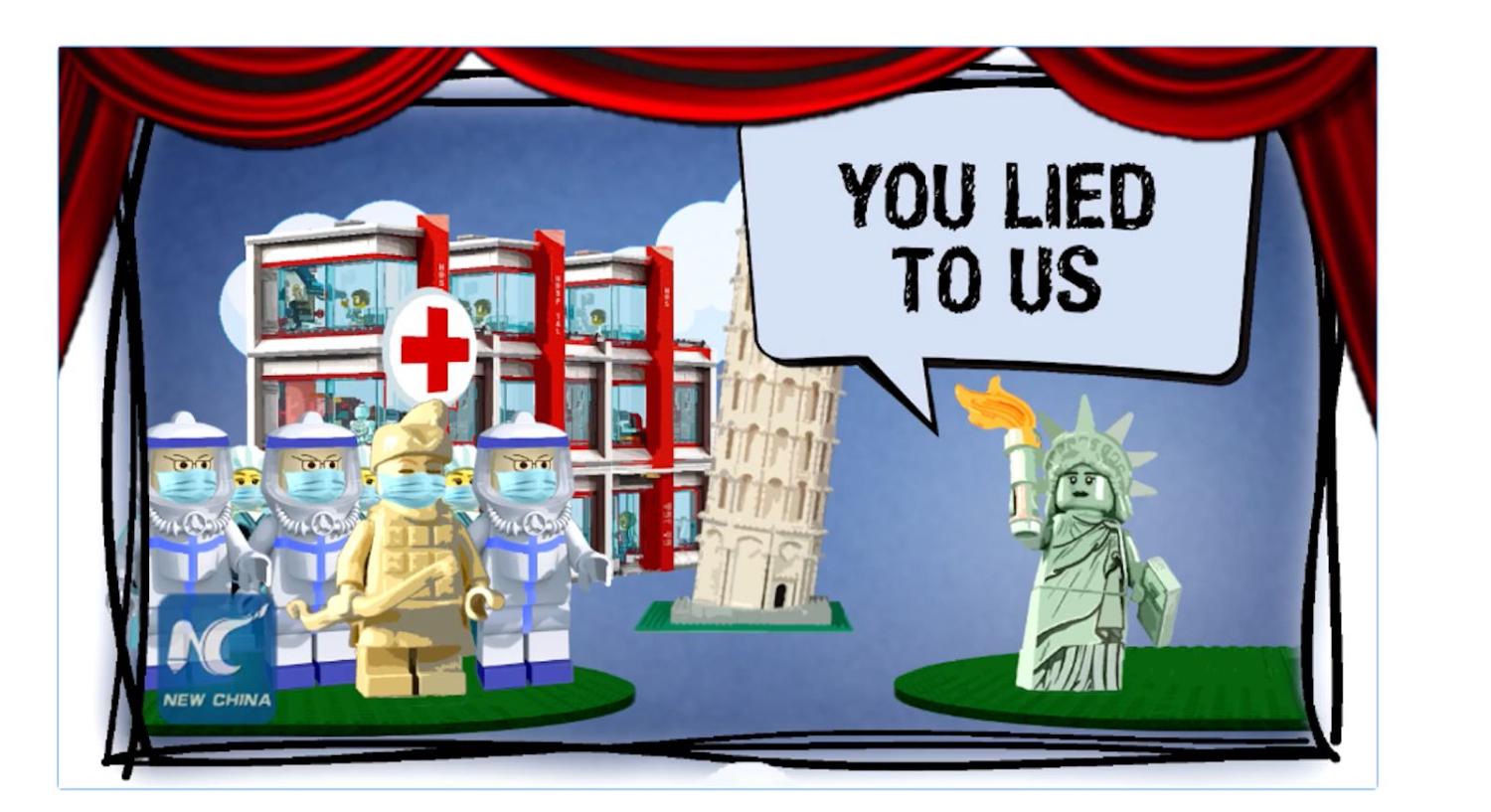

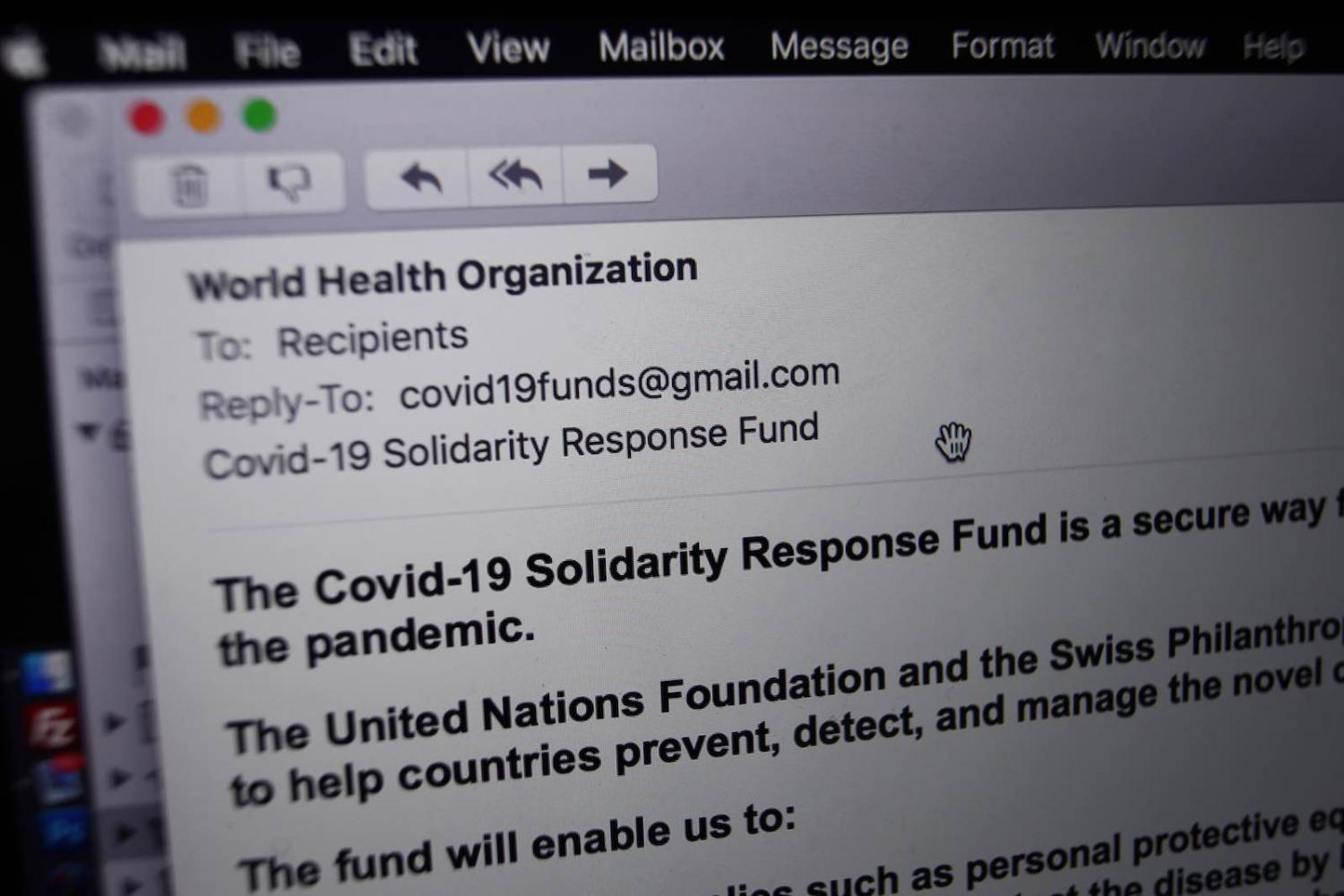

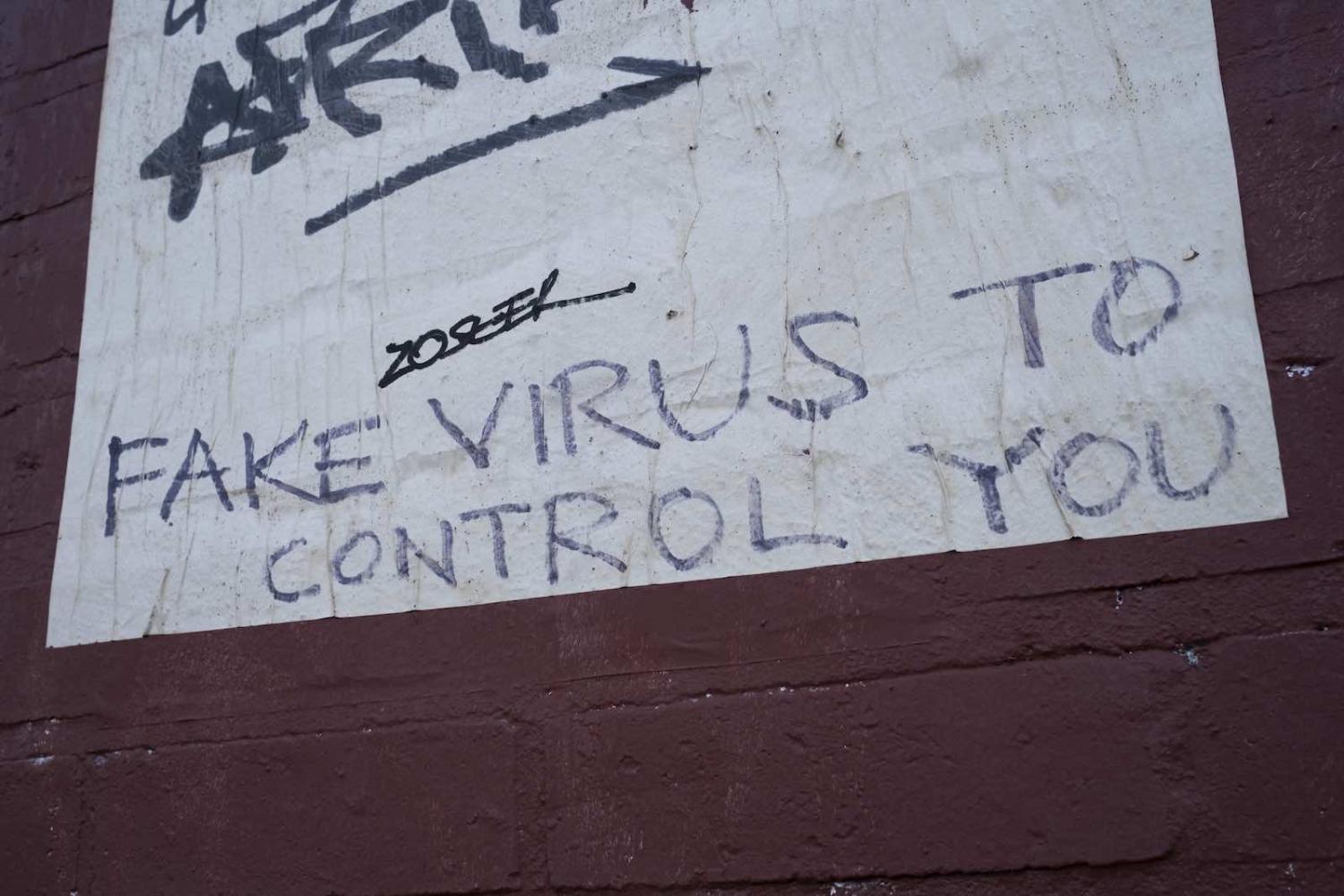

And if a first step to combating a problem is first understanding it, disinformation and conspiracy online was certainly no help. Natasha Kassam:

The dilution of information on the internet is currently posing a risk to global health and safety. Much like globalisation has extended the reach of the virus, social media has extended the reach of fake news. And the stakes are higher.

Bright spots emerged. Enterprising Indonesians mixed their own hand sanitiser, and Bob Kelly – aka BBC Dad – had some helpful advice for those staring at a Zoom meeting working from home:

This will be a slog for the next several months, and my guess is that for all the convenience of telework, most people will enjoy going back to an office when this situation finally breaks.

Nick Bisley wondered at the future power dynamics in Asia. Mark Beeson asked what the crisis might hold for the vaunted international order?

Any of the big issues that collectively confront us – including climate change, economic disadvantage, and, of course, controlling pandemics – would seem to necessitate some form of institutionalised international collaboration.

Countries raced to develop vaccines while wrestling with the rights to privacy when tracing the virus spread. The future design of cities was questioned, we wondered about spies and the warning signs, protecting political leaders from the virus or whether they could strike a global bargain to do better next time?

Jennifer Hsu charted the growing power China’s Xi Jinping amid the pandemic, while Erin Hurley watched Donald Trump shrivel before the challenge. Meantime, Stephen Howes urged the world to remember those most vulnerable:

Covid-19 is hitting at a time when the number of displaced people is at its highest since the end of the Second World War. What if the virus takes hold in a massive refugee camp in Africa, the Middle East or Asia?

Should the world have been better prepared? Shahar Hameiri:

Used to financing and implementing limited interventions far from home, developed states’ governments were suddenly fighting huge contagions on the home front, for which they were often poorly prepared. And since very limited collective capacity had developed previously, their full focus immediately turned inwards, thus producing a fragmented, “zero-sum” response globally.

Or did the world overreact? Ramesh Thakur:

Health professionals are duty-bound to map the best- and worst-case scenarios. Governments bear the responsibility to balance health, economic and social policies. Once these are included in the decision calculus, the political and ethical justification for the hard suppression strategy is less obvious.

Perhaps, in the end, planning doesn’t matter. Gordon Peake and Christian Downie:

Magnified exponentially by these last few weeks, there seems something both absurd yet strangely comforting about feeling emboldened enough to guess a course for endpoints years away … [looking back] planning documents are proof-positive of that old Yogi Berra maxim that the most difficult thing to predict is the future.

Let’s see in 2021 if nature cares that humans can count in years.

Main image via Flickr user 7C0