The reappointment of Subramanyam Jaishankar as the External Affairs Minister of India in Narendra Modi’s third term as Prime Minister was widely expected. However, the inclusion of Pabitra Margherita as a junior minister for the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) came as a surprise. Margherita’s appointment was likely intended to send a signal about the priority placed on India’s Act East Policy – the aims of which are being stymied by the continued fighting in Myanmar.

The Act East Policy (AEP) aims to promote economic development in northeastern India and beyond by fostering closer ties with nations in East and Southeast Asia. Since India gained independence in 1947, the northeast region has been of strategic importance, although it has also suffered from underdevelopment and cultural isolation. The AEP aims to address the issues of the northeast region by promoting economic links across national borders. Once integration occurs, it is anticipated that the northeast would gain access to a broader market and experience an increase in trade and investment.

However, parlous state of overland routes between northeastern India and Myanmar have hindered the development of the suggested integrated zone. As a consequence, little commerce has taken place between northeastern India and Southeast Asia.

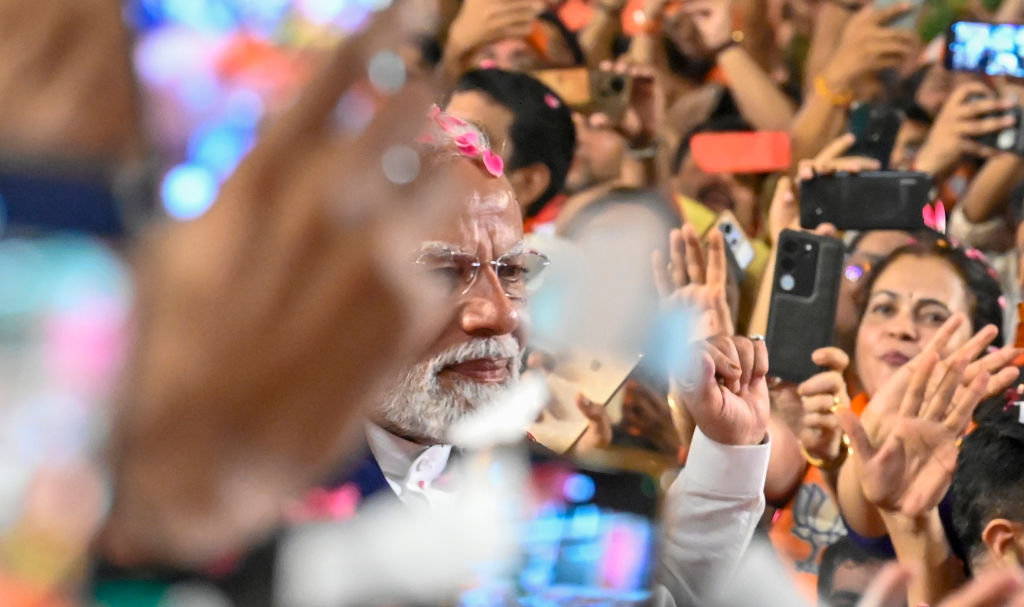

Margherita, pictured, who hails from the state of Assam in northeastern India, is likely to provide fresh momentum in pursuing this flagship policy.

But to do so, Margherita may find himself dragged into the challenging politics of Myanmar’s civil war. The ongoing ethnic tensions in the bordering state of Manipur – India’s “gateway” to Southeast Asia – also threatens undermining India’s grand plans under the AEP. However, instability in Myanmar remains the biggest obstacle for New Delhi in developing the continental routes between northeastern India and beyond.

One major continental route is the ongoing India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway (IMT Highway) project. The highway, which spans approximately 1,360 kilometres, connects Manipur in the northeast with Mae Sot in Thailand via Mandalay and Bagan in Myanmar. In 2023, the Indian government declared that around 70 per cent of the roadway had been completed. Construction has come to a standstill in the remaining 30 per cent of the project due to the ongoing security situation in Myanmar, characterised by intense conflict between the ruling junta and insurgents since 2021.

Another connectivity project is the Trans-Asian railway link between New Delhi and Hanoi, which was approved years ago but has made no progress on the ground. Developing the New Delhi–Hanoi Rail Link mostly involves re-establishing and renovating railway networks in Myanmar as well as connecting Manipur’s Moreh on the northeast India-Myanmar border with the rest of Indian railway.

Finally, the project that is most important to Northeast is the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project (KMTTP) which will connect the eastern Indian seaport of Kolkata with Sittwe seaport in Rakhine State, Myanmar by sea. In Myanmar, it will connect Sittwe seaport to Paletwa in Chin State via the Kaladan river boat route, and from Paletwa to Mizoram state in northeastern India via road. The project is essential to the northeast of India since it would provide an alternate route for shipping products to the landlocked north-eastern states. It will minimise reliance on the existing route known as the Chicken’s Neck in West Bengal, a tiny stretch of land situated between Bhutan and Bangladesh that connects the Northeast to the rest of India. However, the project faces an indefinite setback after Paletwa was captured in January this year by the rebel Arakan Army, leading one senior Myanmar opposition leader to declare the project “almost dead”.

If Margherita’s brief is to keep both IMT Highway and KMTTP alive, he could borrow from China’s approach and directly reach out to various Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAO) under whose control parts of the projects have fallen.

In April 2020, it was reported that Norinco, a Chinese state-owned company that produces weapons, sent ordnances to the Arakan Army in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. This was done to ensure that the insurgent group would not threaten the Kyaukpyu port, funded by Beijing and expected to benefit China's military objectives. Such a policy aligns with the efforts of Chinese policymakers to broaden the PRC's involvement with various stakeholders in Myanmar, with the aim of maintaining favourable conditions for the flow of oil and gas through pipelines into China, as well as ensuring access to Chinese ships and exports by keeping roads and ports open.

Margherita hails from a region that was once the connecting bridge between Myanmar with Bhutan and Tibet – the centre of an extended economic, geographical and social space for the Burmese people. His background, familiarity and experience with the region could enhance India’s chances of collaborating with different actors in Myanmar, so that New Delhi can stay in the good books of whoever eventually emerges in control of the areas through which IMT and KMTTP criss-cross. Indeed, Margherita’s position near the top of the Ministry for External Affairs could unlock the drive needed to push past the bottlenecks in Act East projects.