This year marks the 10th anniversary of India’s “Act East Policy”. Previously known as the “Look East Policy” when launched in the early 1990s, the redesignation by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014 sought to reinvigorate and accelerate India’s eastward engagement. This put India’s ties to Southeast Asia directly in the frame.

India’s present election is consequential for its attempted pivot to the East. The manifestos of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Indian National Congress allude to South-South cooperation in some shape and form. However, only the BJP’s demonstrates an appetite for continuity in strategic engagement with the Indo-Pacific, and by extension Southeast Asia.

For Malaysia, a Southeast Asian nation with its own longstanding look east policy engaging Japan, South Korea and most recently, China, “Act East” semantics are not typically associated with India. This mismatch in perceptions between India and Malaysia could be why it is challenging to quantify the impact of India’s policy on Malaysia after a decade. But it would be an overstatement to claim this has resulted in enhanced strategic engagement, economic relations and connectivity with Malaysia.

Malaysia-India relations have seen bursts of momentum when not mired in the complexities of ties. An Enhanced Strategic Partnership was established in 2015, and regular defence exercises resumed in 2022. The convening of the India-Malaysia Joint Commission Meeting last year after a 12-year hiatus indicated relevant policy settings.

The Malaysia experience is illustrative that country-to-country ties have become increasingly detached from current geopolitical and economic realities.

But economic relations have not kept pace. Indeed, the most significant shift occurred earlier with the 2011 Malaysia-India Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement (MICECA), India’s second free trade agreement with an ASEAN member state. Tariff cuts and liberalisation opportunities on offer failed to boost two-way trade to the levels predicted in early studies, while MICECA’s utilisation rate among companies today lags behind Malaysia’s FTAs with Japan, Australia and Türkiye.

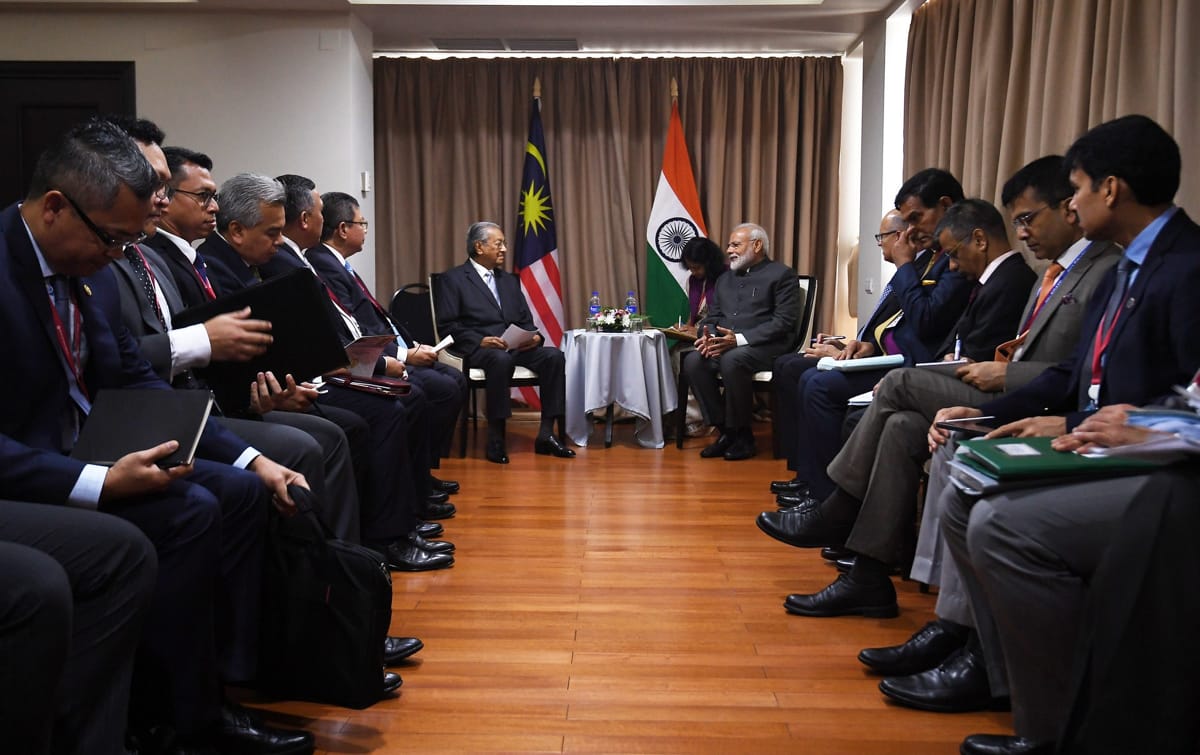

Granted, a flurry of diplomatic visits and the signing of eight new bilateral memoranda of understanding between 2015-17 promised momentum, but that enthusiasm soon gave way to apathy at best and impasse at worst. Trade ties became unpredictable due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the rise in anti-dumping investigations against Malaysia by India, and New Delhi’s temporary imposition of restrictions on palm oil imports following then prime minister Mahathir Mohamad’s remarks on Kashmir. Simultaneously, Malaysia deepened trade with East Asia, particularly China, while India strengthened economic ties with Indonesia, Singapore and the United States.

Trade data reflects these developments. The share of Malaysia-India trade to total Malaysian trade peaked at nearly 4% in 2017 before declining to under 3% presently. India is no longer among Malaysia’s 10 largest trading partners, falling to 12th place in 2023. From 2019 to 2023, bilateral trade growth averaged below 3% per annum, the slowest in two decades, contrary to the objective of “widening” economic engagement.

While relations have picked up since 2023 with a resurgence in high-level visits and an agreement permitting bilateral trade to be settled in Indian rupees, Malaysia risks missing out compared to its more proactive Southeast Asian partners. Singapore, for instance, has been aggressive in pursuing investment opportunities with India: the city state makes up 97% of the region’s total FDI outflows to India since 2000, including, most recently, S$5 billion in announced investments in Tamil Nadu. Indonesia, whose trade with India nearly doubled across 2019–23, has accelerated government-to-government and business-to-business exchange with India in recent years through an economic and financial dialogue and a business forum respectively.

Yet still missing for the region are important mechanics that foster greater ties – transport, most obviously. Many Southeast Asian countries have been advocating for an air connectivity agreement, but domestic interests in India have opposed it. In April 2024, AirAsia announced a new route to Guwahati, Assam, in northeast India. Malaysia’s efforts to seamlessly connect to northeast India, developed as a gateway to Southeast Asia, are commendable. If this paves the way for a wider India-ASEAN agreement, all the better.

In its current structural and functional manifestation, India’s outreach and engagement via its Act East Policy leaves much to be desired. In the case of Malaysia, this can be remedied with an overhaul of the arrangements under the enhanced strategic partnership. Given the vastly different geopolitical context from a decade ago, it should reflect new-age priorities and reflect common objectives for bilateral relations. Updating MICECA could better incorporate current trends in trade, such as e-commerce, small and medium enterprises and supply chain resilience. Additionally, a joint working group between Malaysia’s Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry and India’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry should be set up to resolve challenges such as the growing use of non-tariff barriers and alleged circumvention of FTA-based rules of origin criteria. More importantly, it should map complementary industrial policy instruments, satisfying the call for “joint collaboration”. For instance, Make in India and Malaysia’s New Industrial Master Plan 2030 both identify measures to strengthen value addition and innovation in manufacturing.

Ultimately, the Act East Policy is central to India’s ambitions for deeper engagement with Southeast Asia. But the Malaysia experience is illustrative that country-to-country ties have become increasingly detached from current geopolitical and economic realities. Renewed attention is needed.