Catching up

It is now 25 years since then World Bank senior vice-president and chief economist Joseph Stiglitz remarkably turned on his employer to set out a roadmap for “moving towards the post-Washington Consensus”.

Responding to criticism that the policies of the World Bank and, more importantly, the International Monetary Fund had failed in the Asian financial crisis, Stiglitz embarked on the critique of two of the key enabling institutions of globalisation that he has pretty much dined out on ever since. As he said then:

The policies advanced by the Washington Consensus are hardly complete and sometimes misguided. Making markets work requires more than just low inflation, it requires sound financial regulation, competition policy, and policies to facilitate the transfer of technology, and transparency, to name some fundamental issues neglected by the Washington Consensus.

That was only ten years after the very term “Washington Consensus” had been coined by John Williamson to encapsulate the tough-medicine economic reform principles favoured by the US Treasury and the Washington-based global institutions for fixing the Latin American debt crisis.

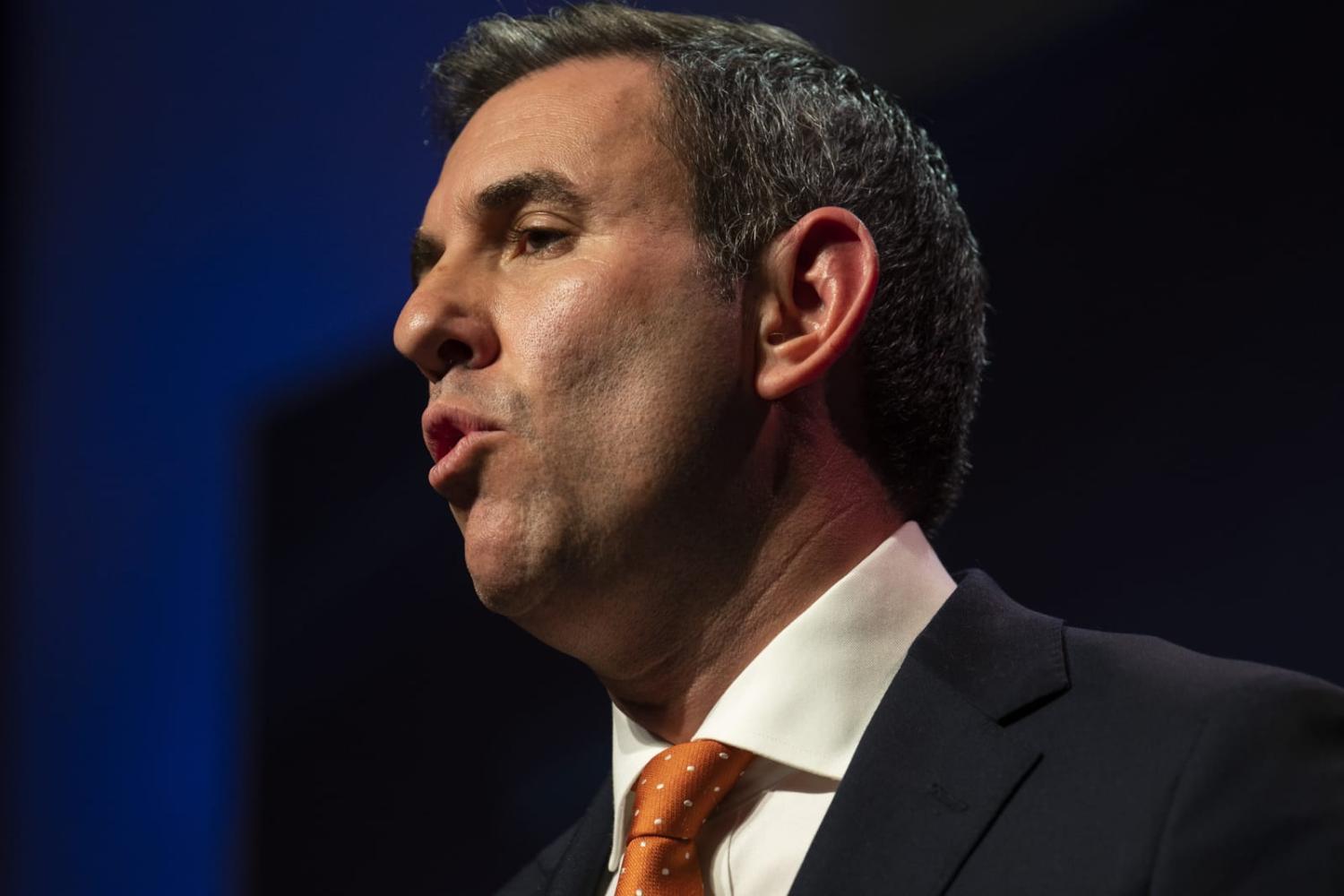

So, it was curious to see Australia’s Treasurer Jim Chalmers skewer the Washington Consensus as emblematic of the outdated or dysfunctional policies that he wants to replace during his time in power. That is because the IMF and World Bank have already been on their own reform journey, as The Interpreter has observed regularly over the years, for example, Stephen Grenville here and Mike Callaghan here.

But writing in The Monthly, as though there had been no change, Chalmers argues that the Washington Consensus had become “a caricature for ever more simplistic and uniform policy prescriptions for ‘more market, not less’. This school of thought assumed that markets would typically self-correct before disaster struck.”

Chalmers' perspective was right a decade or so ago, and both institutions still have problems to address – although they increasingly involve intransigence on the part of powerful member countries. But the IMF has since backed capital controls, called for coordinated global Covid-19 vaccine rollouts, argued climate change spending will ultimately pay for itself, and urged action on cryptocurrency last year when individual governments were more complacent.

In many respects, the IMF provides roadmaps for the well-designed markets Chalmers wants to foster. Indeed, its endorsement of “recovery contributions” back in 2021 from those who had done well out of the pandemic offers a script for Chalmers to rebuild the Australian budget. And then this week, just two days after Chalmers’ essay, the IMF review of Australia gave him even more cover for long overdue reforms including reining in capital gains tax breaks and expanding the consumption tax.

Meanwhile, the World Bank only last month took another step towards a different approach to development aid more driven by the needs of individual countries and the need to play a bigger role in broader global challenges such as climate change.

And like many an opportunistic Treasurer before him, Chalmers has not been able to resist using the imprimatur of the IMF to defend his government’s short-term actions. See a media release last November declaring: “The IMF confirms that the Budget was responsible, right for the times, and readies Australia for the future.”

Chalmers' ambitious endorsement of values-based capitalism – with public-private partnerships to drive a renewable energy shift in a major fossil fuel exporter, a wellbeing budget approach to economic outcomes, and regulation of new technology to help the workforce adapt – may indeed make Australia a petri dish for dealing with some big global challenges.

But he will need to be more in tune with the current global state of play than the tilting at the Washington Consensus seemed to suggest.

Diversification dilemmas

Trade minister Don Farrell finally gets to eyeball his Chinese counterpart Wang Wentao next week, albeit still by videolink underlining the slow dance quality of this putative reconciliation. Farrell’s bosses the prime minister, defence minister and foreign minister have already met their Chinese counterparts in person sometimes more than once, as has his junior minister.

So, it is striking how Farrell still ritually points out in interviews that China is a bigger trading partner for Australia than the United States, Japan, Korea, France and Britain combined when he could easily slide out of frustration into the current negative zeitgeist on the country from population contraction to pandemic management. This seems to hint at a compromise that won’t suit everyone.

But Farrell’s disciplined doggedness possibly reflects the way many of the exporters hurt by the blockage of about $20 billion in commodity exports have been conceding their losses in recent months in contrast to the rhetoric of relatively successful diversification that was more commonly being heard a year ago. And Farrell’s approach is also underpinned by new research showing just how concentrated Australia’s goods exports became this century in terms of both products and markets.

“This narrowing concentration in goods exports poses risks for Australia in an increasingly uncertain international economic and security environment,” trade economists Ron Wickes, Mike Adams and Nicholas Brown say in an Institute for International Trade (IIT) working paper.

They support diversification but the paper highlights how it is up against a trend where Australia’s exports to high growth industrialising countries in South Korea and Southeast Asia (which are respectively ahead and behind Chinese development) have faltered as the China export boom occurred. And their call for a broad suite of productivity enhancing economic reforms at home to boost export diversification probably tends to align them with the critics of Chalmers’ new economics.

Australia’s basic export dependence on China is well known but the IIT paper places it in a sharper context by looking at the change over the past two decades and contrasting that with the past half century of trade. China’s share of Australian goods exports has gone from 5 per cent to 40 per cent in two decades, while Australia’s share of Chinese imports (or export intensity) has doubled from 1.5 per cent to more than 3 per cent Australia’s export intensity with Japan is roughly the same over that time but it is down for the United States, South Korea and Southeast Asia.

Likewise, product intensity has grown from 10 per cent for coal, the top export, in 2001 to 30 per cent for iron ore in 2020. The next intensity of the nine exports went from 32 per cent to 40 per cent.

Rather ironically the former Department and Foreign Affairs and Trade economists conclude “unlike in the half century to 2000 when increasing Australian export diversification was linked to new opportunities across East Asia, a range of measures show increasing export concentration since the beginning of the 21st century” – mainly due to China’s rise.

Meanwhile as education and tourism providers prepare for China’s reopening, the paper has some interesting but tentative double-edged points about services as a diversification path. It points out that at face value services exports have become concentrated like iron ore to China with the education and tourism share of services going from 48 per cent to 62 per cent in the almost two decades to 2019, mainly because of Chinese students.

But the paper suggests that the balance of payments data is not accounting properly for the services provided offshore by the subsidiaries of Australian companies. This is hinted at by the largely unreported special 2018–19 survey of offshore affiliates that has been covered here on The Interpreter.

But whether better accounting for Australian health, financial, architectural and other services exports can really offset the China goods trade dependency and the flood of Chinese, and now also Indian, students is another question.

Three strikes

The new year has kicked off with a reminder that however much governments and companies embrace offshore diversification the significant geographic options remain well defined and limited.

So, events in or around Australia’s three China plus destinations of choice – India, Vietnam and Indonesia – have underlined how a modest China reconciliation may still be attractive enough to some businesses. This seemed to be what the government’s special Southeast Asia envoy Nicholas Moore was pondering in this recent interview where he says of diversification “the question is, what happens next if China does reopen to Australian exporters across these different areas?” And Australian businesspeople are now reportedly flocking back to China.

The massive share price slump for India’s Adani Group following fraud allegations has shown that one of the country’s best connected businessmen and Asia’s erstwhile richest person is still subject to political risk even with his friend and Prime Minister Narendra Modi in power. Adani’s Queensland coal mine is the highest profile Indian investment in Australia and some connection would normally have been a part of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s visit to India this year.

In Vietnam, where Australia has a long established Enhanced Economic Engagement Strategy (EEES), the Xi Jinping-like corruption crackdown by Communist Party secretary general Nguyen Phu Trong has now claimed the jobs of the country’s president and two deputy prime ministers. All were associated with the foreign economic liberalisation implicit in the EEES. Whatever happens with economic reform, at the very least decision making in the Vietnamese bureaucracy seems likely to be paralysed by the corruption campaign and faction fighting.

Meanwhile in Indonesia, where the Albanese government and the Business Council of Australia have been re-emphasising the need for a “Team Australia” approach and more patient investment, the potential flagship Australian Sun Cable renewable energy partnership between billionaires Andrew Forrest and Mike Cannon-Brooks has collapsed. This project had promised a consortium investment approach by Australian, Singaporean and Indonesian partners in a new industry.

While the economic and demographic attractions of India, Vietnam and Indonesia for Australian business remain, these quite different developments in the space of a few weeks show how moving on from the China geographic and product concentration risks will still involve challenges.