Third turn lucky

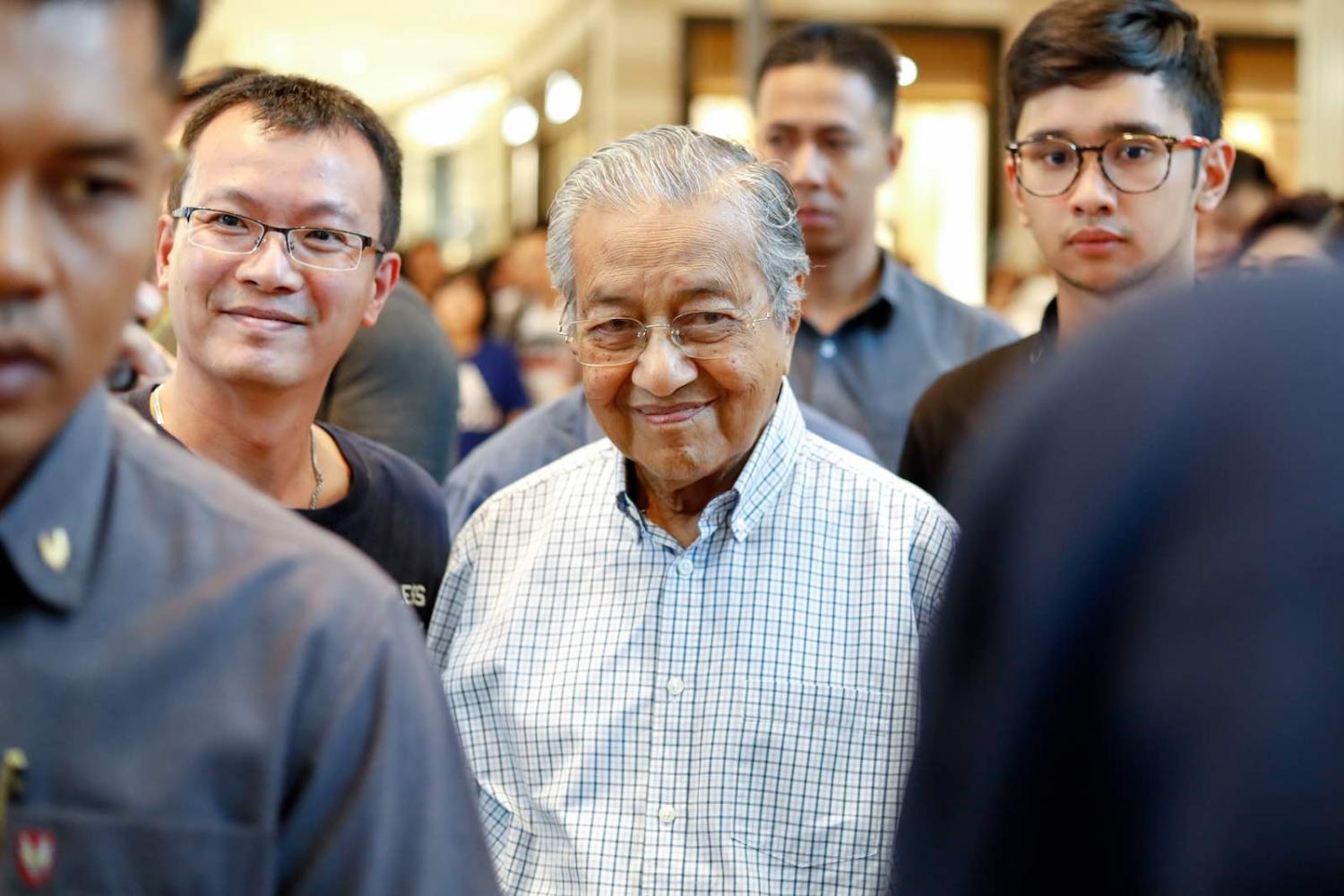

It is no surprise that Mahathir Mohamad appears to be savouring a third coming as Malaysia’s prime minister since all three of the country’s broad political groupings appear to need his support to form a government.

But the parallel question hanging over regional diplomacy is whether the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) group will emerge from this Malay political showdown so lucky.

Mahathir has already blatantly manipulated Malaysia’s status as the host of the APEC Leaders Summit in November to insist that he remain in power for the event, instead of his old rival and promised successor Anwar Ibrahim. This has partly caused this week’s showdown.

But this summit will require some extra diplomatic skill given that the 2018 Papua New Guinea summit – underwritten with more than $100 million in assistance from Australia – didn’t produce a communique. And last year Chile failed to even hold the event due to domestic political tensions, which have some similarity to what’s happening in Malaysia.

Just another day in the office. pic.twitter.com/fU14woEsA0

— Dr Mahathir Mohamad (@chedetofficial) February 25, 2020

Mahathir’s bid for a legacy as the first leader to oversee two summits of the 21-member group was already laden with irony. That’s because of the way his 1998 Malaysian event was overshadowed by the sacking of Anwar as his deputy and his equivocation about APEC’s economic liberalisation approaches.

And regional leaders have a lot more places to meet these days with the East Asia Summit, regular Group of 20 summits in Asia, and leaders level meetings at new institutions such as the new Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. And that’s assuming leaders still have the taste for plurilateral summits in an era of US-led unilateralism.

Malaysia is now facing the same backlash against political uncertainty that Thailand has suffered for years with foreign investors withdrawing US$3 billion from its stock market in the past year and more this week.

The November summit would be a great platform to regain international credibility for a revamped government. But that will depend on Mahathir overcoming his reputation for clinging to power and lukewarm support for global economic institutions. APEC may well be stranded like Anwar.

Taking a slice

The World Bank has cast an interesting new shadow over Australia’s development aid review with research suggesting that about 7.5% of money provided to highly aid dependent countries ends up in offshore bank accounts.

While opinion polls produce some varied voter attitudes to aid spending, this is not the sort of research that the local aid community needs to persuade the government to reverse years of aid cuts – perhaps built around a regional climate change initiative.

And the fact this concession about the extent of corruption comes from within the world’s largest and most influential provider of overseas development aid (ODA) makes it even more of call to arms for new approaches.

The World Bank only agreed to release it when it was leaked. And that conveniently coincided with International Development Minister Alex Hawke telling the Australasian Aid Conference that he had a fixed budget which meant there should be a bigger focus on non-government cash forms of assistance.

The Elite Capture of Foreign Aid study provides evidence of a remarkable parallel rise in deposits in offshore tax haven secret bank accounts when countries receive aid, with the strongest correlation for the most aid dependent countries.

As it observes with understated bluntness:

Disbursements to the most aid-dependent countries coincide with significant increases in deposits held in offshore financial centers known for bank secrecy and private wealth management. Aid capture by ruling politicians, bureaucrats and their cronies is consistent with the totality of observed patterns.

It suggests that aid corresponding to 1% of GDP increases deposits in havens from the recipient country by around 3.4% or an average of 7.5% of the aid flow.

This isn’t as difficult for Australia as it might have been because none of 22 countries on the study's highly dependent list is in Australia’s main aid distribution neighbourhood, and only Laos is on the moderately dependent list. But this appears to be because the list is based on World Bank aid dependence. Pacific countries – which are equally dependent on aid – don’t make the cut because they are typically more dependent on Australian aid.

For example, aid to PNG is about 3% of GDP which would make it moderately dependent by the study definition. But two thirds of that comes from Australia, which means PNG is not defined as dependent on World Bank disbursements.

Aid supporters can take some solace from the study’s observation that the diversion of petroleum revenue from resource rich countries to tax havens is more than two times greater than the aid corruption.

It notes:

The difference may be due to the fact that foreign aid is generally subject to monitoring and control by the donors whereas there are no external constraints on the use of petroleum rents.

PNG budget blues

The Australian government’s decision last year to return to giving direct financial support to Papua New Guinea’s Budget underlined the complexity of dealing with more assertive aid recipients in a time of rising Chinese influence.

It has drawn a backhander from no less than former foreign minister Alexander Downer who oversaw the end of budget support in favour of more directly overseen and controlled individual aid projects in PNG.

But now it has drawn a backhander from no less than former foreign minister Alexander Downer who oversaw the end of budget support in favour of more directly overseen and controlled individual aid projects in PNG in the late 1990s.

Writing in the Australian Financial Review Downer says with undiplomatic frankness: “I didn’t want to see any cash paid into the Papua New Guinea budget.”

That’s quite a contrast to International Development Minister Alex Hawke’s announcement last November that Australia would provide US$300 million “to help Papua New Guinea in its efforts to put its budget on a more sustainable trajectory, assist in the delivery of core government services and support longer term economic reforms.”

That policy reversal was sugar coated by being presented as a loan which avoided any direct coast to the Australian budget and as a benefit to Australian business by improving the liquidity of the kina foreign exchange market.

Downer appeared to deviate even further by backing the need for PNG aid to go to good governance programs when the big new spending by the current government is telecommunications and electricity infrastructure.

But this is the new realpolitik of competition with China and attempting to create development partnerships with a more emboldened host government amid such a large sprawling list of post-budget support individual projects that they are hard to assess.