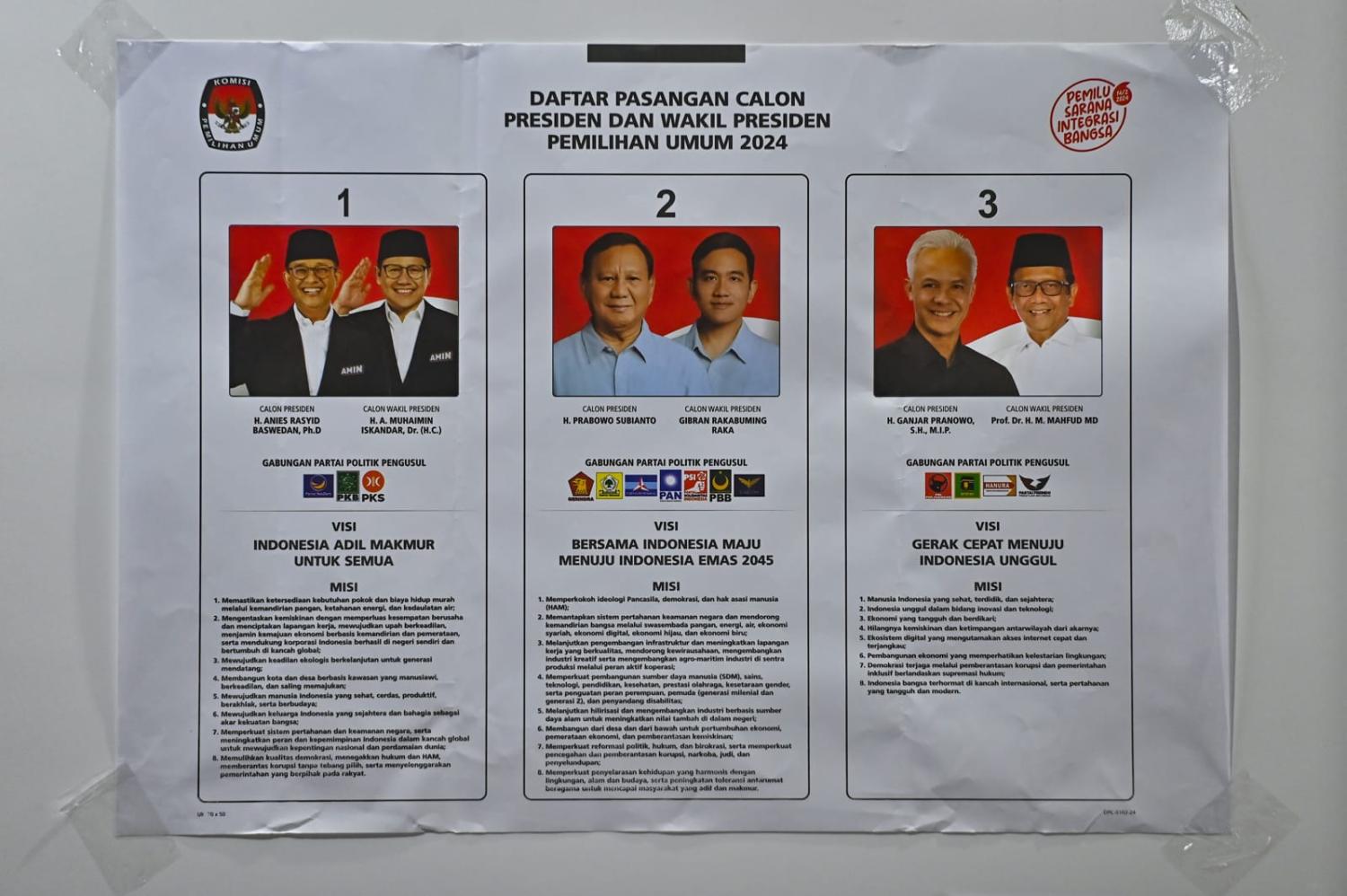

Many eyes across the world will fall on Indonesia this week as the presidential election campaign culminates for what could be the final ballot on 14 February. Should one of the three candidates clearly prevail, a run-off election will not be required. But an enduring question for international observers was given voice in Washington recently, when a former US ambassador to Indonesia sought to probe a delicate topic.

“Most Americans,” he said, “the day after the election, the question that’s going to be on their minds is, ‘Were the elections in Indonesia fair and free?’”

Joseph Donovan was the US ambassador to Indonesia from 2016 to 2020, closely watching the rule of Joko “Jokowi” Widodo and the trajectory of Indonesia’s democracy. He posed his question at a United States Indonesia Society (USINDO) forum in the US capital last month, where visiting representatives from the three Indonesian presidential campaigns, each speaking on a different day, answered forthright questions from Defence and State Department officials, economists, faith leaders, business executives, and academics.

Speaking for the ticket comprising Prabowo Subianto and Gibran Rakabuming Raka was Hashim Djojohadikusumo, appearing online from his Jakarta office. The Prabowo-Gibran campaign has been accused of gaining help from state institutions and from the President himself, with claims of favouritism towards Prabowo, a three-time presidential candidate and present defence minister, and Gibran, one of Jokowi’s sons. Hashim is an accomplished businessman and philanthropist, as well as Prabowo’s younger brother and campaign confidant.

“So, at the moment I’m not aware of major, major problems,” he responded to the question about free and fair elections. “Obviously, some of the candidates, they complain about this, they complain about that. Prabowo has some complaints as well. Those are the normal problems of a democracy.”

Concerns have gone beyond minor gripes, however. The complaints have ranged from a decision by the Constitutional Court then headed by Jokowi’s brother-in-law to tweak the election law to allow Gibran to be Prabowo’s running mate despite not meeting previous age criteria, to Jokowi palming out social aid in the field timed with the campaign period. It has led some analysts to worry that “Indonesia’s election bears the signs of weakening democracy”.

The same question was put to Tom Lembong, representing campaign for former governor of Jakarta Anies Rasyid Baswedan and his running mate Abdul Muhaimin Iskandar. Lembong appeared in person in Washington, and is a Harvard graduate who held trade and investment portfolios under Jokowi. The Anies-Muhaimin campaign has repeatedly called for the neutrality of local authorities and the president as well.

“It’s hardly a secret that the campaign of (defence) minister Prabowo and Gibran are utilising as much as they can all the state’s institutions to benefit their campaign. It is not even a scandalous thing to say in Jakarta anymore. It’s taken as a given,” Lembong said.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Lembong saw the chance for campaigning to extend to a second round, even though Prabowo leads in the opinion polls.

Speaking for the third ticket, that of Ganjar Pranowo and Mahfud Mohommed, was Andika Perkasa, deputy chair of the campaign team. He is a four-star general, a past armed forces commander under Jokowi and earned a PhD from George Washington University. He was asked how Ganjar differs from his two rivals, responding that the former Central Java Governor can be a fast mover to get things done. He pointed to differences in foreign policy emphasis from Jokowi, particularly with regard to China, saying that Ganjar would restart the offshore oil drilling north of the Natuna islands group, an activity Jokowi suspended due to Beijing complaints.

The candidates themselves had addressed foreign policy matters in a formal debate, but a two-minute limit for answers in the televised event meant hot-coal issues were inadequately addressed. The USINDO series allowed questioners to ask at length and for the representative to reply without any cut-off from the moderator.

Lembong, for example, was asked what ideas Anies has to mitigate the damage done by climate change, explaining that the candidate believes in underwriting risks for development of renewable energy that would otherwise be excessive for the private sector to bear. He said Anies wanted to develop transparent mechanisms to underwrite some of the exploration risk.

A faith leader asked of Anies’ position to protect freedom of religious minorities. Lembong said in the five years Anies was in office, Jakarta built more churches than the previous four governors combined. He was the first governor to build crematoria for the Hindu community. And for the first time in a long time, Lembong said, Jakartans could be pleased that five years went by without any single raid on bars and places of nighttime entertainment by right wing or radical vigilantes. But he notably left out that as governor, Anies engaged hardline Islamic groups, and apparently this association dissuaded them to attack bars and similar outlets on the eve of the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan.

Hashim was quizzed about perceptions of two binding constraints to Indonesia’s economic growth: human capital and governance, and what Prabowo’s plans are for the Corruption Eradication Commission, KPK, and its independence. He was further asked how to improve the quality of the judiciary, which is critical for dispute resolution, especially investor disputes.

Hashim said Prabowo plans to strengthen KPK and its independence by adding “hundreds of investigators.” On the judiciary, Prabowo will increase the salaries of judges, prosecutors as well as the police and military.

An Defence official asked about the South China Sea, and how Prabowo would address “coercive behaviour”. This led Hashim to outline Prabowo’s pledge to increase the Indonesian defence budget from 0.8 per cent of GDP, one of the lowest among the G20 members, to between 1.5-2 per cent of GDP, a boost in spending of up to US$30 billion a year. This wasn’t meant to foreshadow fireworks. On China’s nine-dash-line claim of several thousand square kilometres of Indonesia’s economic zone, Hashim said Indonesia will have “to come to an amicable solution with them.”

“I can’t tell you what it’s going to be like. But we’d like to negotiate. We’d like to avoid conflict,” he said of Prabowo’s thinking.

On Wednesday, Indonesia decides.