In crossing the border from Belgium to the Netherlands, a young man named Djamaluddin Adinegoro extracted the contents of his small travel bag. Because there was a border, you might immediately recognise that this event took place many years ago – almost a century, in fact. And out of the bag alongside assorted toiletry items tumbled a collection of large notebooks containing figures and written notes in Dutch, French, English and Malay. Half the notes were in Arabic script.

The traveller explained to the customs officer that the notes were for a periodical in the East Indies, the territory now known as Indonesia.

The customs agent asked one question. “Are you carrying firearms?”

No, was the reply.

“Where is your other luggage?”

On a ship from Marseille to Rotterdam.

This exchange is narrated in the 1930 book, Melawat ke Barat, or Journey to the West. The book compiles articles that Adinegoro despatched about 1920s Europe to three outlets, including Pandji Poestaka (Book Banner), a Jakarta-based magazine published in Bahasa Indonesia. The stories generated such great demand that they were reprinted in bound form in three volumes.

If John Gunther famously had his 1936 Inside Europe, Adinegoro already had his in 1930.

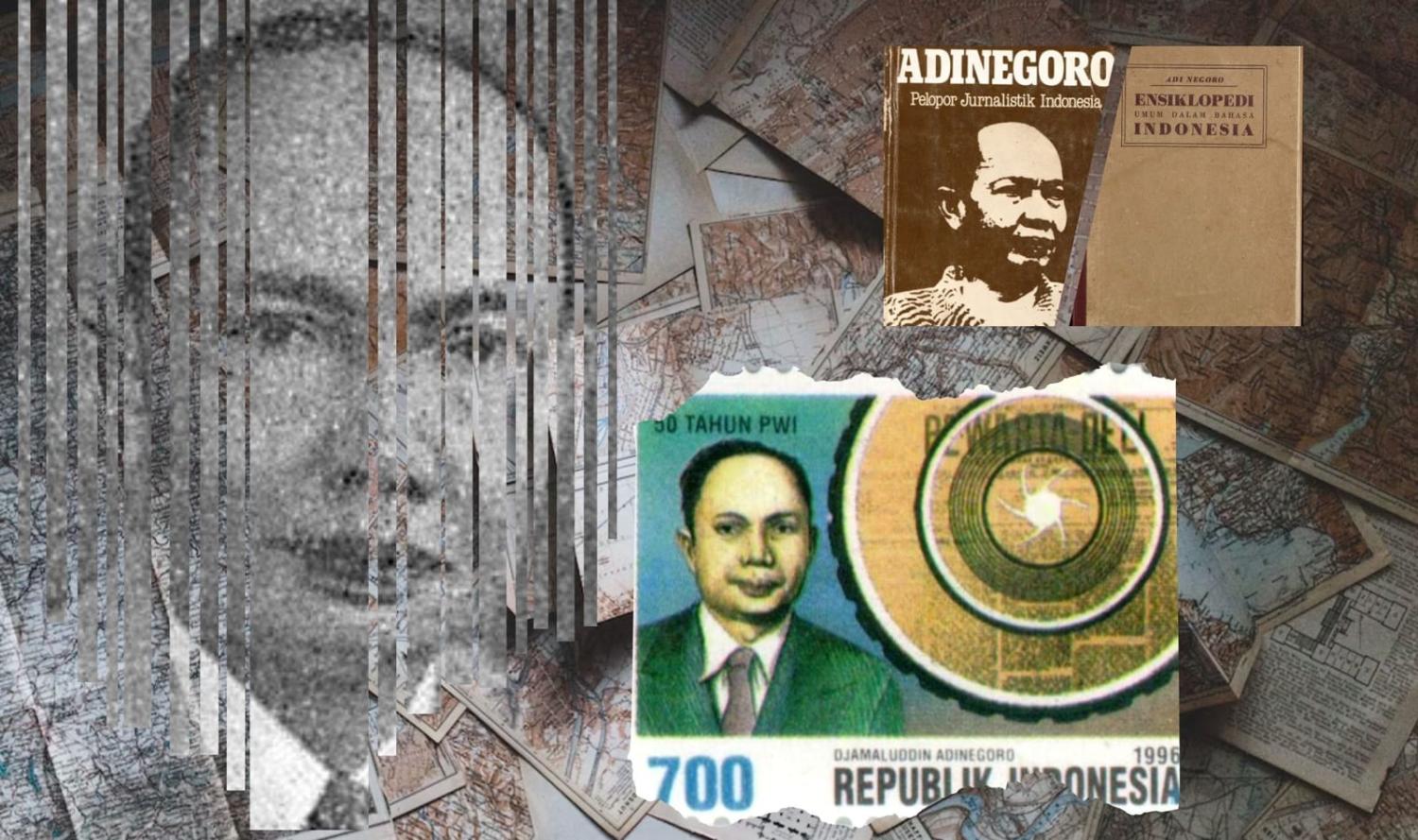

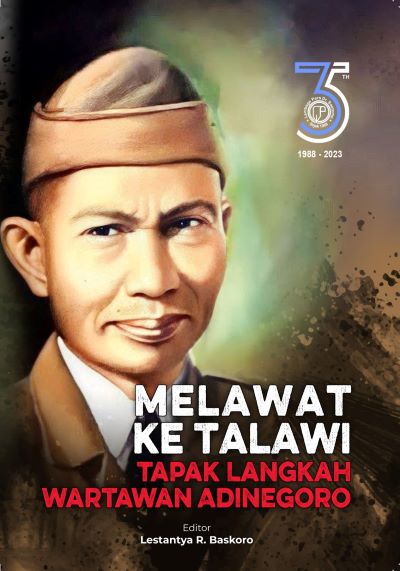

The singular story of this multi-lingual reporter is told in a new biography released last month. Titled Melawat ke Talawi, Tapak Langkah Wartawan Adinegoro, (Departure from Talawi, Adinegoro’s Journey in Journalism), by Lestantya R. Baskoro, past executive editor of the newsweekly Tempo, the book traces Adinegoro’s life all the way from his birth in 1904 in the rural town of Talawi in Sawahlunto district, West Sumatra.

Adinegoro, the son of a demang or minor administration official, was educated in a Dutch language colonial-era school. With an astute mind for languages and a driving urge to discover the world under his feet, Adinegoro sailed to Europe from Batavia, now Jakarta, in 1926 aged 22.

The final call of the passenger ship Tambora was Rotterdam, but when the ship docked at Marseille, its first European port, Adinegoro decided to make France his starting point. His reporting took him throughout the continent to Türkiye over the next four years.

In returning to Indonesia, Adinegoro became chief editor of the magazine he contributed to, co-founded journalism schools in Jakarta and Bandung, and was recognised as a press leader and icon.

But his forte was writing books. He published 25 titles. They were not only reportage and primers, public opinion and politics, but also a brace of novels. He also wrote the first atlas and encyclopedia in the Indonesian language – he had studied cartography in Germany – as well as a book in German on political culture.

Of these works, Journey to the West is arguably the best known. To the point that Balai Pustaka (Book Gallery), publisher of the 1930 edition, has repeatedly published it, the latest in 2017.

Travelling through Europe six years after the end of the First World War, then called the Great War, Adinegoro focused on how major conflict affected the countries of the continent. In France, Adinegoro reported on war damage and losses. He contrasted the before and after social and economic statistics, such as in population and production. Of the millions of dead, wounded or disabled, Adinegoro wrote:

A college lecturer said, ‘nine out of ten young men under 30 years old who would later replace us are gone. Older people like me are grieved in that it is like we are in the middle of a desert.’

And in the aftermath of the war, Adinegoro carried ominous foreboding:

Although the nations of Europe feel the hurt and misery stemming from the 1914–1918 war, and there are countries still in deep pain, instances emerge of a returning urge for an armed clash. Our hearts tremble when we think of a war that will come. For the war will be ten times fiercer than the previous one.

Adinegoro’s book came out before John Gunther’s. But Gunther’s book was timely, appearing in 1936 when the three dictators Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin were at the height of their pre-war power.

Adinegoro’s work has enduring relevance, however, not least in the contemporary era where the storm clouds of conflict gather again. Indonesian journalists today actively report on the urgings of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and how Indonesia individually relates to external powers that affect the region. The national press is also keen to cover military issues such as joint exercises, as well as international economic links, many of which are seen in the context of global competition.

Adinegoro’s name outlives the man who died in 1967, age 62. Since 1974, honouring his contribution to the profession, the Association of Indonesian Journalists, PWI, has bestowed the annual Adinegoro Journalism Award to winners in seven competitive categories on National Press Day, 9 February, with each winner receiving a cash prize of 30 million rupiah (US$2,000). This includes prizes for in-depth reporting, editorial writing and social media video journalism. And as his biographer Baskoro concludes:

Adinegoro is the mirror of what a journalist should be – even in this digital era – critical, tenacious, and defend[ing] the public’s interest.