As 2019 winds up, Lowy Institute staff and Interpreter contributors offer their favourite books, articles, films, or TV programs this year.

Ross Garnaut’s Superpower has already been reviewed on The Intepreter. But can I include it in the context of “favourites for 2019”? This book marks not one, but two turning points in the climate debate. The first concerns the economics of renewable electricity. The second is in public opinion.

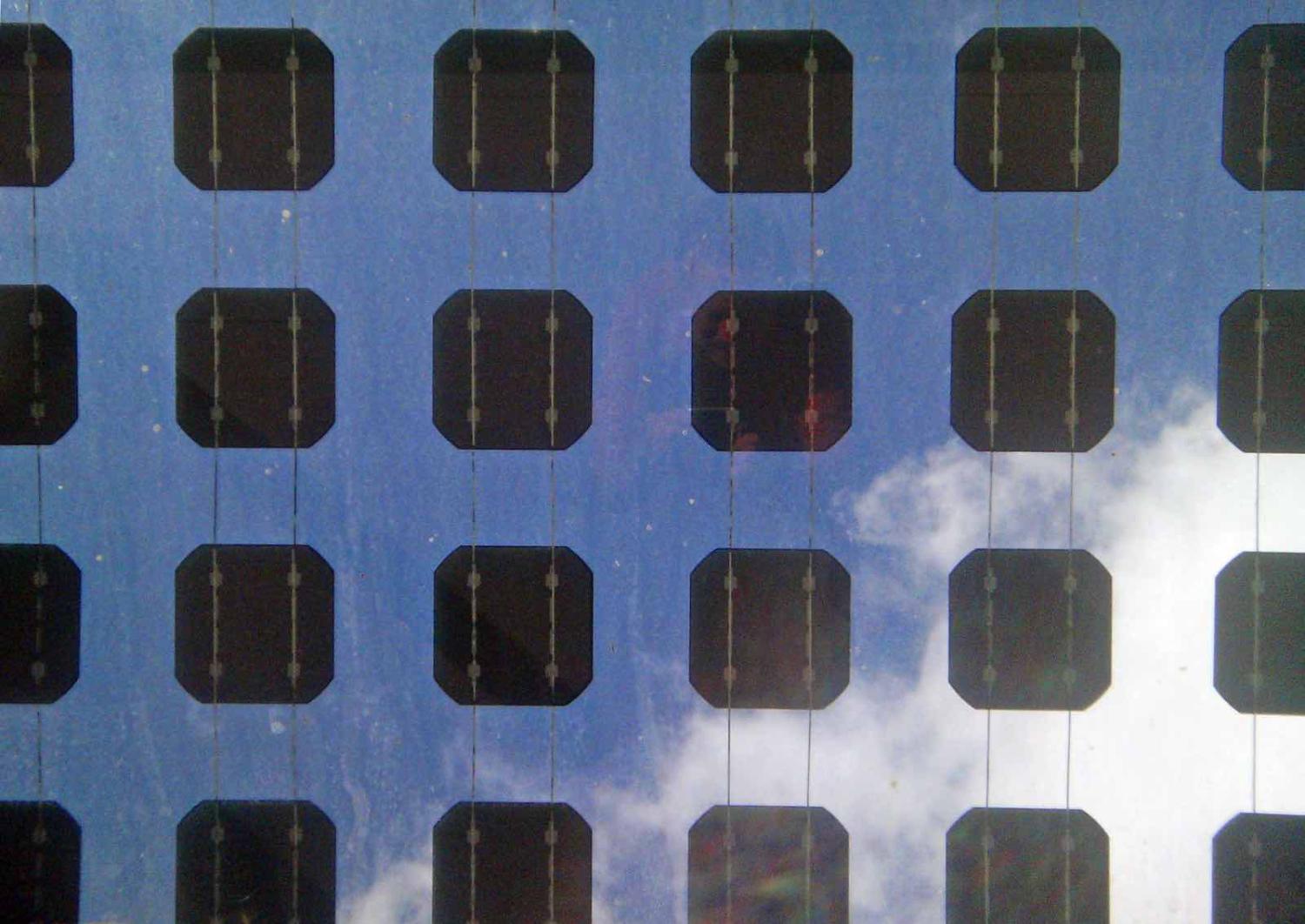

While the news media is still filled with gloomy narratives about impending climate doom, Garnaut’s message is both revolutionary and positive. The economics of renewable electricity is crossing a fundamental threshhold. Until recently it was debatable whether generating renewable electricity was profitable for a private entrepreneur or household, without distortionary subsidies or regulatory compulsion.

While the news media is still filled with gloomy narratives about impending climate doom, Garnaut’s message is both revolutionary and positive. The economics of renewable electricity is crossing a fundamental threshhold. Until recently it was debatable whether generating renewable electricity was profitable for a private entrepreneur or household, without distortionary subsidies or regulatory compulsion.

Even when optimists pointed to the fall in the cost of renewables, the sceptics would rehearse the problem of intermittency: the sun doesn’t always shine nor the winds blow constantly. South Australia’s problems in 2016, with their multiple causes, are taken as a demonstration of renewables’ failure.

What is the evidence that things are changing?

Exhibit One is the behaviour of the coal-based generators: they want to close down their plants. They will continue to operate only thanks to government pressure. Whereas some of us used to worry that the coal-generation lobby would want to keep their industry going forever, they want out.

Exhibit Two is that within all the fraught politics of the carbon debate, the problem of intermittency is being addressed. Not solved, to be sure. But addressed with substantive examples of the way forward. Snowy 2.0, South Australia’s Big Battery, and connectors between grids (including Tasmania’s hydro) illustrate what can and should be done. And these projects have been initiated with a federal government that displays little concern for the climate and a strong private-sector ethos. How miraculous is that?

Garnaut is so confident that renewable electricity is now profitable that his plan does not propose a carbon tax: the incentives are positive, even without a tax. And it would be even more profitable with the sort of taxes that are now common in Europe.

Let’s contemplate just how revolutionary it would be if the cost of stable renewable electricity (i.e., with intermittency addressed) were competitive with coal. Australians could divert our energies from the wearying arguments about who or what is causing climate change, how it will affect us, and how soon. Even those who say it is not man-made can’t argue against taking action to produce electricity by the cheapest means.

If generating renewable electricity is now profitable, without subsidies or regulatory compulsion, everything changes.

The intractable problem of collective action shrinks. No longer are we waiting around for someone else to take costly action on climate change. It’s in our own interest to cease “free-riding” and to take action ourselves, because this is the cheapest way to generate electricity. This is true, even for the developing economies which have used their poverty as a reason for inaction.

Contrast this with the earlier head-butting debate. All the sceptics had to do was to introduce an element of doubt about the climate science. For their part, the scientists who advocated action sometimes exaggerated the size and imminence of the disaster, to try to stir some action. When action was taken, the true costs were often fudged in order to reduce the criticism, disguising subsidies and regulatory advantages for renewables. No one was fooled: we were all paying more for our electricity when solar generators were offered over-the-top feedback tariffs or there was a compulsory quota of renewable generation.

Meanwhile, economists were trying to sell the idea that all you had to do was tax carbon and the problem would be solved. As Tony Abbott noted, any tax big enough to change consumer behaviour would overwhelm the budgets of ordinary electricity consumers: his “great big new tax on everything” jibe was a winner for the deniers.

But if generating renewable electricity is now profitable, without subsidies or regulatory compulsion, everything changes. There is no need to subsidise, or distort decisions through regulatory compulsion or dissemble about costs of action. It will happen by itself, if the market environment is right.

What’s needed is a well-functioning market, some coordination, and enhanced scale. The emphasis shifts away from direct actions, picking winners, and placating vested interests. Instead, the focus is on addressing obvious market failures, coordination, and enhancing scale.

Coordination and addressing market failures presents a formidable challenge, but a fascinating task for micro-economists. Markets are good at sorting out coordination problems over time, but might need some regulatory help in the transition.

The key point here, however, is that this kind of government intervention and coordination is not market-distortionary: it corrects market failures. Even the most dogmatic free-marketeer should agree.

What about the second threshhold: public opinion? Public support for climate-change action has waxed and waned (as tracking the Lowy Poll over the years makes clear), but is again peaking. This is not just a result of the bush fires. Nor is it just in Australia. Even in the corridors of staid central banks, climate risk is now topic-du-jour.

If the Morrison government could find the courage to shift its attitude on climate, it would find that it is pushing on an open door of public opinion.