The last five years have been a rollercoaster for Australia-France relations: a cancelled submarine contract, a major breakdown in bilateral ties, and now a steady recovery building towards a “bilateral roadmap”. More recently, President Emmanuel Macron’s positioning of France as a puissance d’équilibre – a balancing power – in strategic competition between the United States and China has cast doubts in Australian and American minds about France’s reliability as a long term partner in the Indo-Pacific – concern over comments by Macron in April regarding Taiwan and the response it generated are symptomatic of this.

In this context, a new options paper from the Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy and Defence Dialogue – the first major report on Australia-France ties since AUKUS – examines how Canberra should recalibrate its relationship with Paris to enhance collaboration in the Indo-Pacific.

This starts with understanding the provenance of French strategic culture, driven by a Gaullist tradition that privileges French sovereign decision making and autonomy. While France’s interests and actions align far more closely with those of the United States and its allies, France is firm in its view that it will engage in the world on this basis. The critical point for Australia is to recognise how France’s words and actions, while not always perfectly echoing its own, sit within this broader tradition of strategic thought.

While putting a lower ceiling on bilateral trust, the 2021 rupture in Franco-Australian relations has forced both sides to develop a more realistic understanding of each other. France now has greater clarity about Australia’s strategic outlook and alliance priorities. At the same time, Australia miscalculated the importance of the submarines to France’s overarching Indo-Pacific strategy. While there is convergence between the two countries’ visions for the Indo-Pacific, Australia needs to understand how France’s strategic outlook and relative priorities differ from its own.

France’s more independent stance within strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific also offers opportunities for Australia. Working with France may give greater space for Australia to influence parts of the region that are reluctant to be seen to be “taking sides” with either the United States or China. In particular, Australia should consider how its language around “strategic equilibrium” might dovetail with France’s “balancing power” position. Similarly, there may be openings for Australia and France to coordinate on the substance of messaging but generate greater influence by speaking with different voices – for instance, on human rights, regional relations with China and Russia, and awareness of malign foreign influence.

Australia must also see France’s Indo-Pacific engagement in its global context. Australia should not underestimate how much French bandwidth is consumed by its ongoing role in Africa, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and broader North Atlantic security. Moreover, with most hard assets positioned around metropolitan France, distance prevents their rapid deployment to the Indo-Pacific. The French Senate has also raised questions about whether France’s resource allocation and depth of strategy in the Indo-Pacific really match its rhetoric.

In working closely with France in the region, Australia must manage risks and sensitivities in frank terms. The first is around the complexity of maintaining relationships with the semi-autonomous French territories in the Pacific – in particular, how New Caledonia and French Polynesia engage in groupings such as the Pacific Islands Forum on essentially the same terms as sovereign nations, even though foreign relations and other key policy domains remain under the purview of Paris. Australia needs to be cognisant of how interests can diverge between overseas and metropolitan France and navigate this complexity over time. Canberra wants to maintain good relationships with both Paris and local authorities and populations in French territories – not least because those territories might one day become independent nations.

The second risk lies in how France acts and is perceived in the Pacific. Resentment and distrust over France’s nuclear testing last century, colonial history and ongoing sovereignty over parts of the Pacific persist in parts of the region. Developments in recent years around New Caledonia’s status, especially the 2021 independence referendum, have added to this. More broadly, French engagement in the Pacific is often regarded as inconsistent and more top-down, with less engagement with local needs and preferences when compared to Australia’s approach. There are risks to Australia’s own relationships and equities in the Pacific if it perceived as being too close or sympathetic to France, or if it uncritically accepts all French positions.

Nonetheless, there are positive signs that France will ramp up its Indo-Pacific role in terms of a greater permanent military presence, an expanded diplomatic footprint, and a larger development contribution in the Pacific. Australia should look to identify challenges areas across the Indo-Pacific where France has particular advantages and capacities that intersect with Australian interests. Thematically, France has strengths it can bring to bear in development (such as environmental and climate security and infrastructure) and the governance of territorial waters (such as maritime domain awareness and exclusive economic zone monitoring).

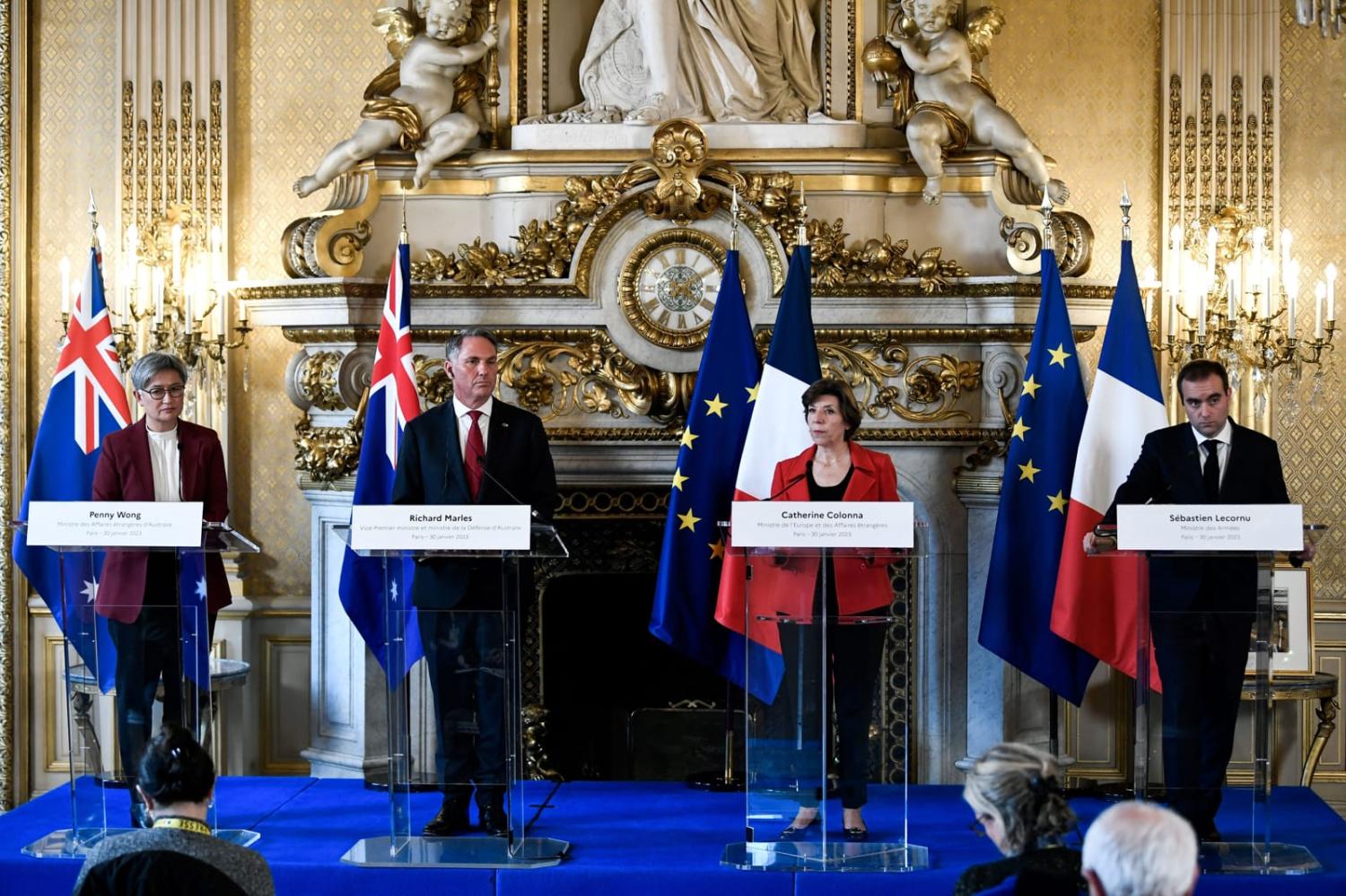

While engaging France on French priorities gives Australia leverage to influence Paris’ decision making, there is a balance to be struck between relative priorities. Australia should structure the 2+2 Ministerial Consultations and officials dialogues to focus on the Indo-Pacific. Within this, Australia should ensure that the bilateral roadmap is framed around meeting the needs of the region. Premising Australia-France cooperation solely in terms of strategic competition will be counterproductive to effective coordination and relational influence, especially in the Pacific.

This article draws on an AP4D report, What does it look like for Australia to enhance coordination with France in the Indo-Pacific, funded by the Australian Civil-Military Centre. Thanks to all those involved in consultations to produce the report.