The future of US democracy seemed in the balance when, in mid-2019, candidate Joe Biden promised to host a “Summit for Democracy” within his first year office. His win didn’t dispel those fears. The 6 January Capitol riot prompted declarations that the Summit was needed more than ever. The White House put revitalising democracy “the world over” at the heart of its Interim National Security Guidance, released in March.

But administration’s enthusiasm for the Summit appears to have waned. The virtual Summit will take place just inside the deadline, from 9–10 December. Few details have been released. The event in December will be the first of two. It will have three themes: defending against authoritarianism, addressing, and fighting corruption and advancing respect for human rights. And it will “provide a platform for leaders to make both individual and collective commitments to defend democracy and human rights at home and abroad”.

Democracies around the world face a list of challenges that has grown well beyond the Summit’s three themes. It includes inequality, civic participation, disinformation, safeguarding electoral systems, illicit finance, emerging technology, large corporations, transnational populism and authoritarian regimes.

These challenges are primarily domestic, but not exclusively so. As scholar John Ikenberry has persuasively argued, the health of individual democracies depends, at least in part, on democracy’s global health. The fewer democracies there are, the harder it is for them to avoid a race to the bottom, obtain critical mass and deal with common problems collectively.

But the Summit could turn out to be yet another good idea that is executed poorly. Another platform for meaningless democracy rhetoric would be a step backwards. At the other end of the spectrum, a rigid “Alliance of Democracies” could counterproductively exclude partial or flawed democracies, of which there are many; especially if it adopted an agenda of assertive democracy promotion.

The United States should more clearly distinguish democracy promotion from democracy protection.

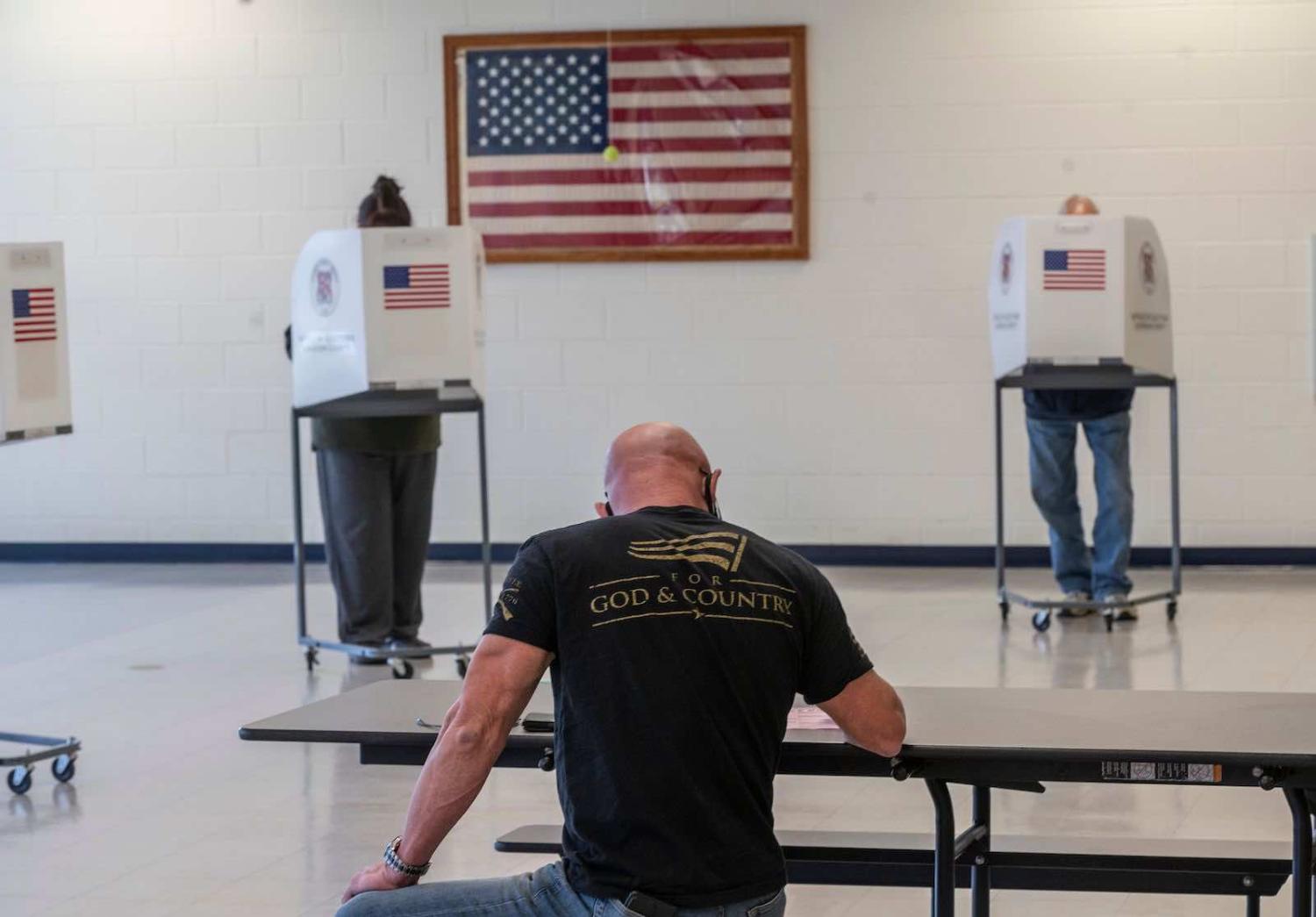

Washington should set a realistic objective which aligns with US capabilities. The starting point should be recognition that US authority has been weakened by its own democratic shortcomings. The signs here are promising. Administration figures have struck a suitably humble note when discussing democracy abroad. The Summit itself is intended to “showcase one of democracy’s unique strengths: the ability to acknowledge its weaknesses and imperfections and confront them openly and transparently”.

The United States should more clearly distinguish democracy promotion from democracy protection. Despite the rhetoric, the administration’s record so far shows limited US will or ability to expand the democratic world. The withdrawal from Afghanistan was a stark reminder that Biden’s concept of international democracy promotion shares nothing with the democracy evangelism of the neoconservatives. The administration’s practical action against non-democracies has been limited. It’s included targeted sanctions (Syria and Myanmar), visa restrictions (Latin America and Belarus) and reduced military support (Saudi Arabia and Egypt).

Democracy protection requires more than just domestic reform or demonstrating that, as Biden is fond of saying, “that democracy can still deliver”. It requires increased cooperation between existing democracies.

These issues on which democracies must cooperate more often hard to deal with internationally precisely because they have a sensitive domestic or commercial dimension. Governments don’t want to wash their dirty linen in public and are leery of giving other countries a commercial advantage by sharing information on the regulation of foreign investment, let alone coordinating on market access issues.

On the other hand, democracies are better at cooperating with one another than other regime types. Open systems can engage at more levels and create more trust. The advances in counter-terrorism provide a good example of international cooperation on issues once deemed purely domestic. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s global minimum corporate tax rate could herald more cooperation on geoeconomics.

With which democracies should the US cooperate? Smaller groups that have more in common can do more. That logic has driven a wider trend towards more minilateralism, including the evolution of groups such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (United States, India, Japan, Australia) and AUKUS (Australia, United Kingdom, United States). It underlies the proposed D-10 Initiative. Exclusive democratic “clubs” can have a wider positive effect: Turkey undertook democratic reforms when it remained hopeful of entering the European Union.

But there are costs to exclusivity. Implicitly badging others states as undemocratic can encourage democratic backsliding, as happened after Turkey’s EU accession bid was botched. It can also fracture democratic groupings: the United States is still repairing the diplomatic damage done by excluding France from AUKUS. And it can create an obstacle to cooperation elsewhere, including the efforts to counter authoritarian states.

The best way to offset the cost of minilateralism – exclusion – is through more minilateralism. To balance the competing imperatives of inclusivity and effectiveness, Washington should aim to produce multiple new democratic groupings. These groups could be organised according to the issues on which they are prepared to cooperate. Some may only be prepared to do so on one or two issues. States prepared to cooperate on the widest array of issues could form a core group.

The Summit itself should be treated as the start of an application process rather than constitutive of a new group. The high number of partial or flawed democracies in the world – all of which base their legitimacy – at least in part – on their democratic credentials creates an opportunity that can be leveraged. The event should be open to any democracy willing to admit that it has problems, and to seek help.

Biden should set the tone with an introspective reflection on US democracy and on areas of possible international cooperation. That would encourage others to follow suit. Any country that refused to admit problems would appear absurd and exclude itself from the benefits of membership.