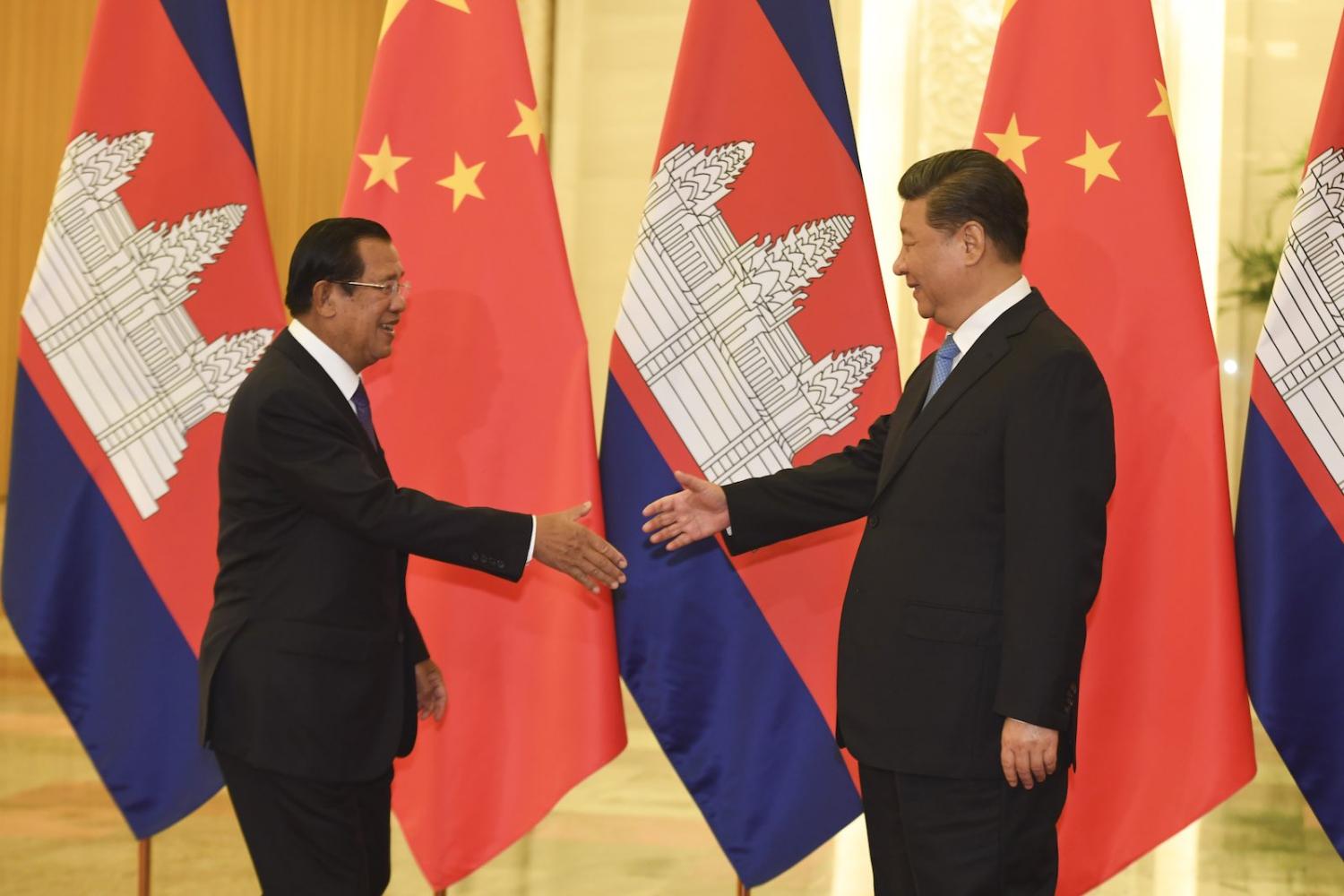

On the sidelines of the second Belt and Road Forum in China last month, Cambodia’s Hun Sen was busy. He secured a further $90 million defence grant from Beijing, adding to the $100 million already pledged in June last year. The defence deal was one of at least nine agreements signed with China at the forum. He also met with China’s President Xi Jinping, Prime Minister Le Keqiang and politburo member Wang Huning. China has committed to import 400,000 tones of Cambodian rice and also struck a deal to allow Huawei to build Cambodia’s 5G network.

Adhering to convention, Hun Sen later took to Facebook to express his appreciation of the bilateral relationship, writing:

As comprehensive strategic partners and ironclad friends, we are siblings who share a single future.

The agreements and meetings all reaffirm the view of Phnom Penh firmly in Beijing’s orbit, and of the Belt and Road initiative as a full spectrum strategic project, be it economic and/or military.

Cambodia’s tilt towards China has been gaining further momentum as the European Union moves closer to revoking the “Everything but Arms” (EBA) trade scheme. This program has allowed Phnom Penh to export products, with the exception of armaments, to the EU at reduced tariff rates. But the EU threatens to put a stop to scheme in response to Cambodia’s worsening human rights record, with the November 2017 dissolution of the opposition Cambodia National Rescue party (CNRP) leaving what is now effectively a one-party authoritarian state.

At the Belt and Road Forum, Beijing pledged to provide assistance to Cambodia if the EU implements trade sanctions. The loss of any preferential trade arrangements with the EU will only deepen Sino-Cambodian relations, negatively impact the Cambodian population, and set back any chances of restoring some level of respect for human rights and the rule of law.

Beijing is Cambodia’s biggest economic influence and the relationship has delivered significant benefits for both countries. China has gained almost exclusive access to infrastructure and connectivity development (i.e., the Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone), with Beijing also an obliging partner in trade, investment and military spending, one that turns a blind eye to Cambodia’s declining civil and political rights environment. Hun Sen’s Cambodia has found a natural bilateral “bestie” in Xi’s China.

China-Cambodia defence ties have been getting steadily closer since 2010. Beijing is now the largest donor of military aid to Phnom Penh and in March, China and Cambodia held the third iteration of the “Golden Dragon” exercises – the biggest display of the defence ties between both countries to date. With Cambodia suspending military exercises indefinitely with the United States in January 2017, this signals a complete departure from Western and EU partners.

China-Cambodia military exercises and Beijing’s investment in Cambodia’s defence sector are perhaps obvious manifestations of the wider relationship. The $90 million defence grant is not the first (nor will it be the last), but in the current political climate it signals renewed reassurance of Chinese support towards Cambodia. At the regional level, it confirms that Beijing remains committed to befriending like-minded states and forming soft alliances, in which there are no formal legal documents between the two parties but evidence of concrete action.

Given China’s generous defence funding and recurring military exercises with Cambodia, it’s doubtful that Beijing will be happy to leave the relationship there.

Ongoing expressions of Sino-Cambodian defence ties and deepening economic engagement are bound to generate unease within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. While Phnom Penh has remained firm in its China policy and most states within the region appear to accept the fact that Cambodia is a Chinese client state, the ongoing relationship is being watched closely by ASEAN. There are still unresolved territorial disputes in the South China Sea and Sino-Cambodian defence ties will have implications for intra-ASEAN relations.

China’s increasingly close relationships with Cambodia (as well as Myanmar) raises questions for ASEAN’s effectiveness in the coming decades. With ASEAN characterised by consensual decision-making, sharp divergences of interests between Chinese client states and those members more wary of Beijing could paralyse the organisation. This is of concern for Australia and countries such as Japan, as ASEAN-centrality is often held up as a core principle of East Asian and Indo-Pacific security architecture embodied in groupings such as the ASEAN Regional Forum and the larger East Asia Summit.

Add in the exclusivity of this relationship, Hun Sen’s increasing authoritarian rule and the mutual mistrust towards the Trump administration, the deepening of the Sino-Cambodia relationship is certain to stir discomfort in the US, too.

Given China’s generous defence funding and recurring military exercises with Cambodia, it’s doubtful that Beijing will be happy to leave the relationship there. As a client state, Cambodia will ultimately have to grant China military access when it asks – and it will. Rumours of a potential Chinese military base were reignited earlier in the year, following the docking of Chinese warships in the coastal city of Sihanoukville.

In 2008, Hun Sen granted a 99-year land concession in Koh Kong province to the private Chinese company Union Development Group. The 45,000 hectares of real estate and 20% of Cambodian coastline is set to be the site of a Chinese tourism mega-hub, but the suspiciously long airport runway and deep-water port point to ulterior motives. Satellite images further confirm such suspicions.

With the US set to unveil a new Indo-Pacific strategy at the Shangri-La Dialogue at the end of May, it can be expected that the Trump Administration will condemn Beijing’s militarisation of the South China Sea and emphasise the continue conduct of Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs). Chinese client states may also come under greater scrutiny, given the ASEAN grouping will be crucial for the realisation of the next Indo-Pacific strategy.