Bangladesh is now facing a serous dilemma over the future of 1.2 million Rohingya Muslim refugees from Myanmar. Its efforts to contain and isolate them from the mainstream community risk creating an alienated, extremist community. Australia has played an important role in helping to meet immediate humanitarian needs, but there are now much graver problems on the horizon.

The Rohingyas are a Muslim minority group, expelled from Myanmar’s Rakhine state by government security forces in 2017. While the Rohingya community traces its origins to pre-colonial days, they are also more or less a demographic extension of Bangladesh – there is little to distinguish them from Bangladeshis. Myanmar’s Buddhist majority regime have long seen them as outsiders.

The long-term dispossession of the Rohingyas creates several security threats for the whole region. These are to a large extent latent but will not remain so for long.

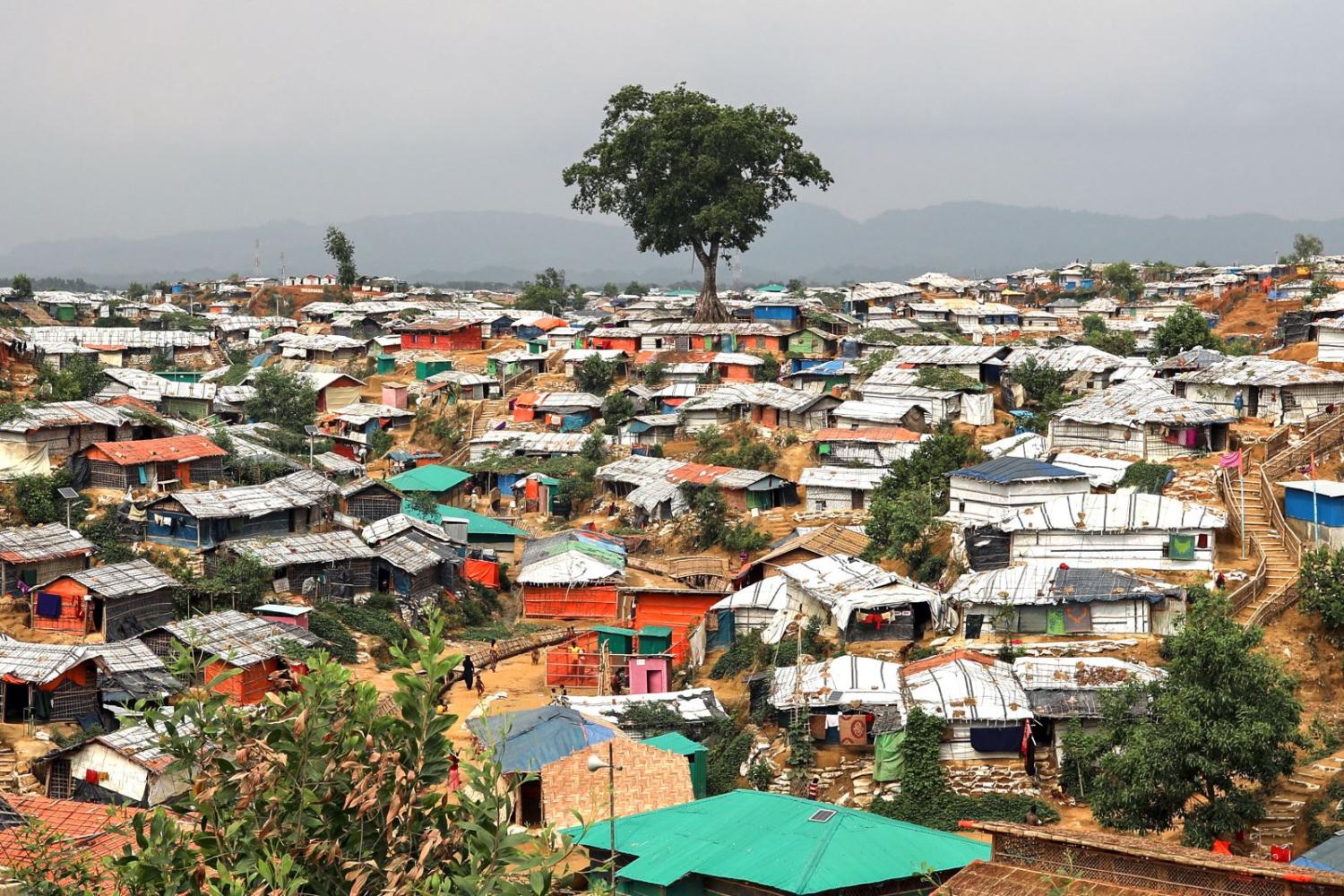

Over a million Rohingyas are currently housed in the world’s largest refugee camp near Cox’s Bazar, close to the Myanmar border. With significant international assistance, the immediate humanitarian crisis has passed, but the Rohingyas’ future is bleak. They are discouraged from leaving the camp and forbidden from working.

Bangladesh policy has been to contain the dispossessed Rohingyas, prevent them from integrating into mainstream society and ensure that their stay is not permanent. Indeed, it is the dearest wish of the Bangladesh government and the Rohingyas that they return to their homes as soon as possible (although in many cases their homes have been burned or bulldozed by Myanmar government forces).

But Rohingyan leaders are demanding security and recognition of their status as Myanmar citizens as preconditions to their return. Neither of those conditions will be met any time soon. For one thing, the security environment has only worsened since they were driven from Myanmar. Around 120,000 Rohingyas who remain in Rakhine state have been confined to internally displaced persons camps. Since early 2019 fighting has also intensified between Myanmar government forces and the “Arakan Army”, a local Rakhine Buddhist insurgent group.

Nor is it likely that Myanmar will grant them any meaningful form of citizenship. The Myanmar regime has now largely achieved its decades-long goal of expelling the Rohingyas, and there seems little reason for them to reverse the new status quo. China and India, the two big powers in the region, have explicitly or implicitly backed the regime. The Modi government has mirrored the Myanmar government line, calling Rohingyas “illegal Bengalis” and “terrorists.”

The long-term dispossession of the Rohingyas creates several security threats for the whole region. These are to a large extent latent but will not remain so for long.

One big concern is the potential for violent extremism. Ongoing attempts by Bangladeshi and foreign extremists to radicalise Rohingyas have not yet gained much traction, but it is difficult to imagine that this will last as more than a million people sit in the camps without any future.

Second, is the potential for the camps to be a base for a cross-border insurgency. There have already been (relatively amateurish) attacks by Rohingya groups against Myanmar security forces. Although the Bangladesh authorities could probably limit activities by Rohinghyan insurgents, there is potential for nasty cross-border incidents between Myanmar and Bangladesh forces.

Possibly the biggest immediate threat is the potential for the Rohingya community to become a conduit for drugs into Bangladesh. The lack of economic opportunities in Myanmar have already forced some people into illegitimate activities such as drug distribution, including a particularly addictive form of methamphetamine known as “Ya ba” produced in labs in Myanmar’s ungoverned spaces. Without any legitimate source of income in Bangladesh, there is a high risk of the development of networks for smuggling and distribution of Ya ba throughout Bangladesh with potential to destabilise the community.

The Bangladesh authorities have been trying to contain the Rohingyas until they go home. Last year the community forcefully resisted efforts to encourage their “voluntary” return to Myanmar without guarantees of security and status – which of course could not be provided.

The Bangladesh government is proposing to move large numbers of people from the existing, relatively porous, camp to the uninhabited Bhasan Char island. The island is around three hours by boat from the mainland, making it easy to control movements (both in and out). The Bangladesh Navy has, at considerable expense, built accommodation there for some 100,000 people with potential accommodation for another 100,000.

But international aid donors and NGOs – which the Bangladesh government depends on to run the camps, are resisting the forced removal of refugees to what is essentially an isolated sandbank (although Australia, of course, with its own reliance on offshore islands for asylum seeker processing is not in a position to object too strongly). There are significant doubts that efforts to relocate Rohingyas to Bhasan Char will be successful, and it is not clear what the government intends to do with the remainder of people in the Cox’s Bazar camp.

What are Australia’s stakes? The headline concern (for Australia and others) is the potential for unregulated population movements. So far, movements of Rohingyas out of Bangladesh have mostly been to neighbouring India, Thailand and Malaysia. But growing networks across the region will facilitate onward movements to Australia, if and when, large numbers of people decide to move. This can only become more likely as Rohingyas come to the realisation that there is no return to Myanmar and (perhaps) little future in Bangladesh.

But Australia has a much deeper stake in the stability and security of Bangladesh. The creation of a permanently dispossessed people of South Asia has the potential to damage the regional security in ways that we may not yet imagine – just as the plight of the Palestinians has left a permanent scar on the Middle East.

Australia has been generous in addressing the immediate humanitarian crisis of their dispossession, but there are more serious problems looming. Bangladesh’s efforts to contain the Rohingya community are likely to fail and we need to be working on the step beyond that.

David Brewster travelled to Bangladesh as a guest of the Bangladeshi government.