India officially launches its Covid vaccination program tomorrow (16 January) in a major logistical exercise aiming to inoculate hundreds of millions of people. And with it, the hustle begins. India, just like China, will be looking to leverage the diplomatic benefit of its ability to manufacture vast amounts of the vaccines, and the manoeuvrings of middlemen and foreigners to tap India’s supply will likely begin in earnest.

India is already the world’s largest manufacturer of vaccines. If this works, its drive to stamp out Covid-19 could potentially change the country’s fortunes and deliver it the global reputational boost it so craves.

The AstraZeneca vaccine, which is known locally as Covidshield, was approved for manufacture some weeks ago, along with a locally designed vaccine by Bharat Biotech.

Doctors and other front-line medical workers, will be the first to get the vaccine – all 30 million of them. Next in line will be those aged over 50 and sick or immunocompromised people. Some Indians will have to wait months to receive their dose; however, anyone with a few extra rupees in their pocket will be able to access it via the country’s sprawling private medical market. The vaccination drive is – initially, at least – being funded by the government, which will pay 250 rupees (around $3) per dose. The vaccine will also be available on the private market, priced at around 1000 rupees.

Already, other countries around the world have reportedly requested access to India’s stocks. It’s another signal of the growing faith that the global community has in India’s ability to deliver.

The company manufacturing Covidshield, Serum Institute of India, says it has already stockpiled tens of millions of doses, and will be looking to manufacture up to 100 million doses each month.

If it achieves this, it will be an extraordinary, almost superhuman effort, in a place that truly needs a superhuman effort to contain the Covid spread. India, with a recorded 10.5 million infections and 152,000 deaths, is second only to the US. (Although it’s worth noting that India has three times the population size and much higher population density compared to the US.)

The details of the vaccination manufacturing program are worth diving into. SII, owned by the sixth-richest family in India, the Poonawallas, had already been working to boost manufacturing capacity, and early on in the pandemic essentially cleared its decks to focus on preparing for large-scale production. Now, SII says it can make 1.5 to 2 billion doses each year. Bloomberg encouragingly called it “The World’s Best Hope for Enough Covid-19 Vaccines”. It helps that the chief executive officer, Adar Poonawalla – a fixture of India’s high-society circuit – is answerable to just one shareholder: his father. Such nimble responsiveness to a health crisis takes these very conditions: a surfeit of wealth, and a lack of barriers (like shareholders).

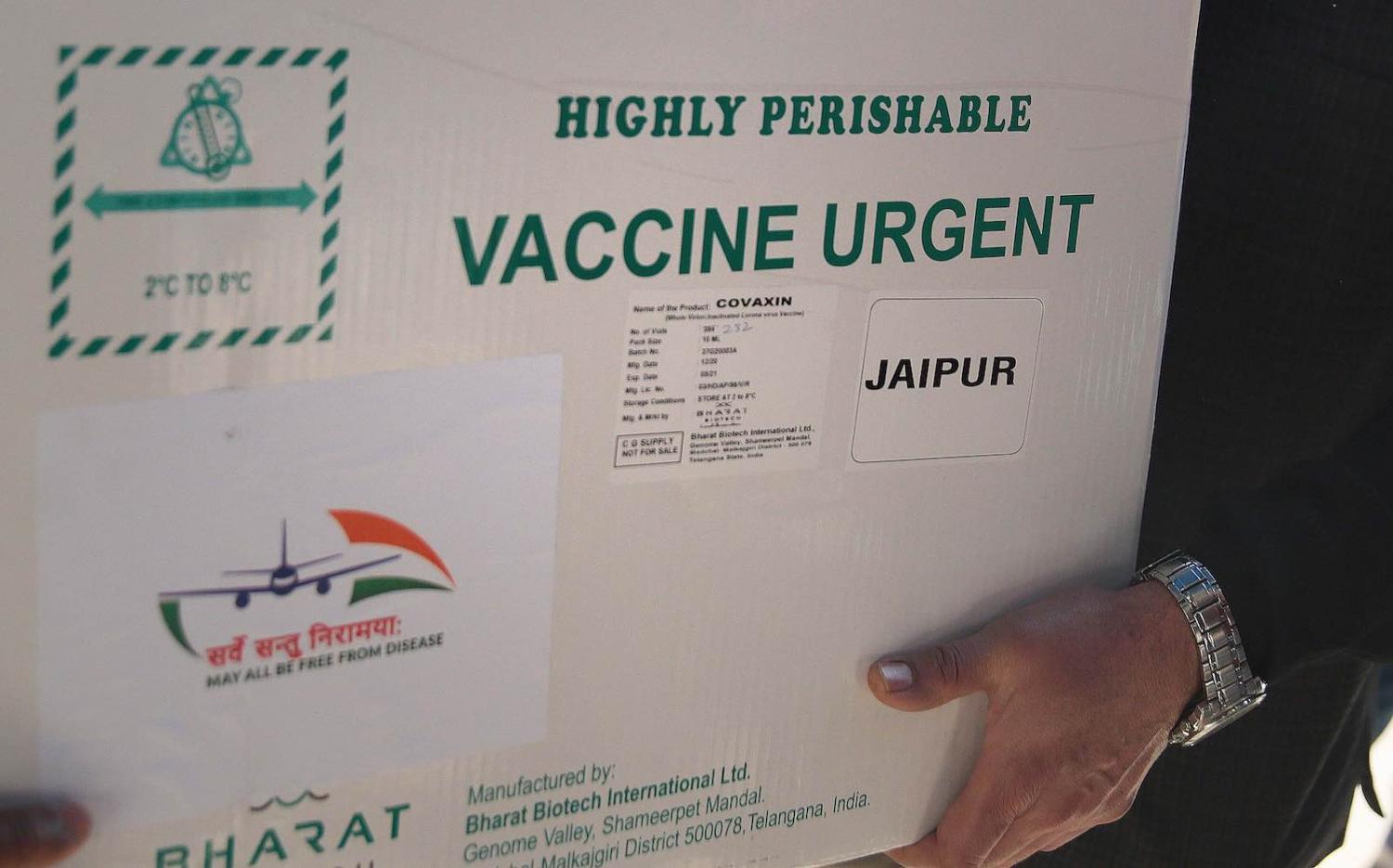

The other vaccine that has been approved, by Bharat Biotech, is called Covaxin. There is a swirl of controversy around this one, as medical staff and scientists say there isn’t adequate evidence around its efficacy, and they are concerned it has been approved too soon. Nevertheless, it is already in circulation, and vaccine recipients reportedly won’t get a say in whether they receive Covidshield or Covaxin.

Already, other countries around the world have reportedly requested access to India’s stocks. It’s reported that Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Myanmar, Bangladesh and South Africa are amongst the countries requesting vaccine stocks. President Jair Bolsonaro has requested two million doses for Brazil, even though he had earlier been sceptical of Covid-19. It’s another signal of the growing faith that the global community has in India’s ability to deliver.

At the same time, there are signs that India’s existing medical tourism infrastructure will be massively boosted thanks to the vaccine, with anecdotal reports of foreigners looking to head there to fast-track their inoculations. I’m hearing that Americans, particularly those holding Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) visas, will fly to India and submit to the 14-day quarantine period, rather than wait more than six months at home.

Travel from the US to India is restricted but still permissible, unlike from the UK, which is currently banned. Still, an enterprising private members concierge service has started offering its high net-worth clients the option of flying to India or Saudi Arabia for the jab. The company says it is speaking with doctors in Marrakech to set up clinics there to administer the Indian-manufactured AstraZeneca vaccine, to get around the UK-India travel issues.

To its great credit, the Indian government has seemingly very pragmatically stepped aside and let the private sector do its thing. After all, India’s notoriously shambolic bureaucracy does not lend itself well to efficient service delivery. Even the logistics is being handled privately, with low-cost carrier SpiceJet amongst those given the task of moving the vaccine around the country and even internationally.

This hasn’t stopped Prime Minister Narendra Modi from nationalising the glory. “India is ready to save humanity with two ‘Made In India’ vaccines,” he said last week.

India is also using the vaccine as a way to win some regional hearts and minds, reportedly set to gift about 10 million doses to its fellow South Asian neighbours – Afghanistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka and the Maldives (although notably, not Pakistan). It mirrors how China is similarly conducting its own vaccine diplomacy as a way to expand its influence in Asia, by gifting doses of its own vaccines to neighbours it wants to court.

Vaccine diplomacy will not solve India’s myriad other problems – underemployment, climate change, a sluggish economy, right-wing extremism – but it is clear that as the world races to reach normality, India may well find itself in pole position.