Last month, as Prime Minister of Mauritius Pravind Jugnauth celebrated his victory in the long-running Chagos Islands dispute, he could hardly have imagined he would be forced to leave office just weeks later. After years of legal battles, Mauritius finally regained sovereignty over the Chagos Islands, ending a contentious standoff with the United Kingdom.

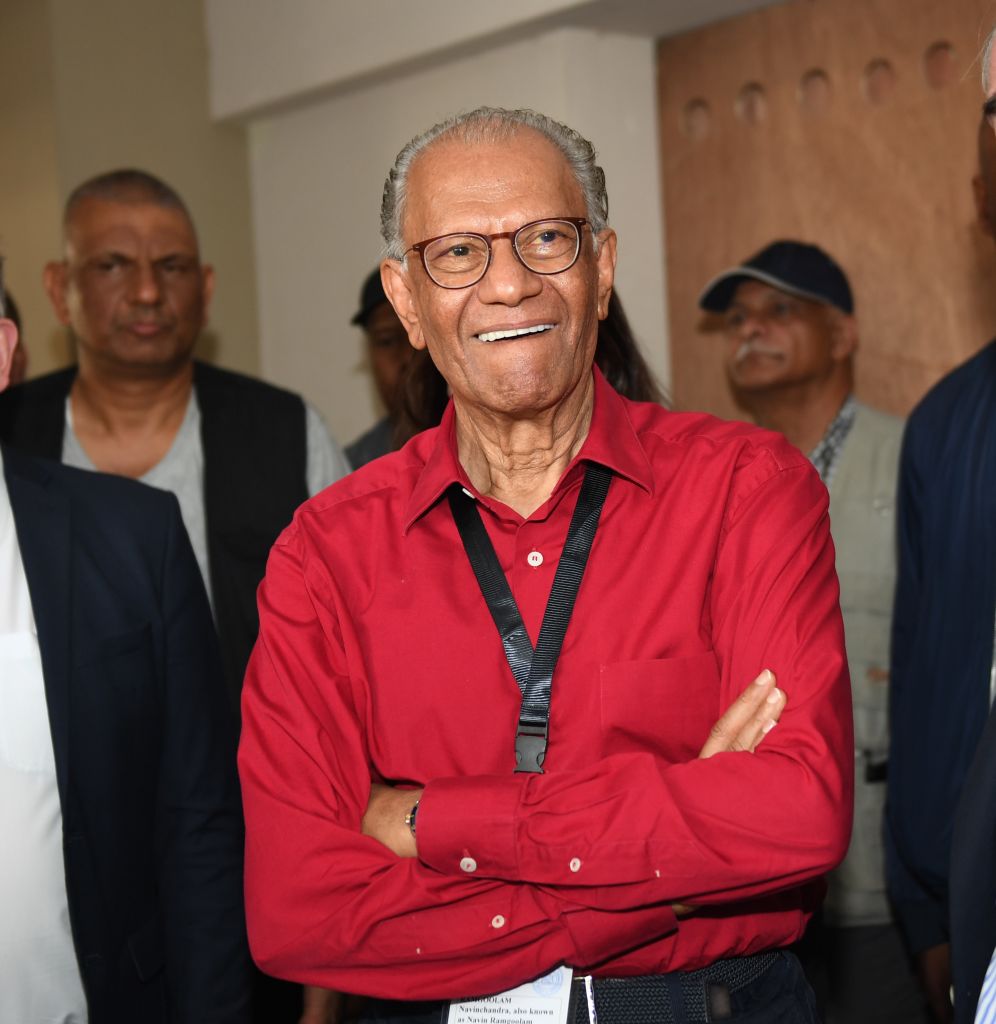

Yet, in a deadly blow to his hopes of a smooth reelection, the opposition leader Navin Ramgoolam won in Mauritius’s parliamentary run-off. And, when judging the scale of the victory, 60 out of 62 seats, with 62.6% of total votes, it is evident that there was widespread discontent against the PM and his ruling coalition, “L’Alliance Lepep”.

Mauritius, the small island nation in the Western Indian Ocean, held elections on 10 November. Despite a GDP above $10,000 in 2022 and steady economic growth of 6-7%, many Mauritians have struggled with the rising cost of living. The cost-of-living crisis was worsened by a growing narco-economy, destroying many young lives. Promises to increase wages, boost pensions, and reduce taxed on essentials were not sufficient to address public discontent.

Furthermore, the campaign was marked by political infighting and a brutal wiretapping scandal. Just a month before the election, a series of private phone conversations involving high-profile political figures, police officers, lawyers, journalists, and members of various civil society organisations began to surface on a local YouTube channel called “Missie Moustass”.

In response, the government insisted that the entire recording had been fabricated using artificial intelligence. However, the situation changed dramatically when the government announced a social media ban before the election. Although the ban was lifted the following day, the damage had already been done. The controversy surrounding the alleged wiretap fuelled a growing wave of anti-incumbent sentiment, and the social media ban was seen as the final straw for Jugnauth.

As Mauritius, a predominantly Hindu nation, stands on the brink of political change, concerns are rising over its future relations, especially in light of India’s deteriorating ties with its neighbours, the Maldives and Sri Lanka. Both these countries witnessed a change of government recently. While India’s relationship with Sri Lanka’s new communist government under Anura Dissanayake has remained stable, ties with the Maldives soured dramatically, particularly due to his “India out, China in” campaign. The pro-China president of the Maldives, Mohamed Muizzu, has been at the centre of several accusations and cross-accusations, further complicating the diplomatic landscape.

Relations have improved since Muizzu visited India last month. But any political deadlock with Mauritius similar to the one in the Maldives would still be a cause for concern. Furthermore, India’s previous attempt to develop Assumption Island in neighbouring Seychelles – an effort that was met with significant local opposition and ultimately abandoned – remains a lingering issue in India’s foreign policy outlook.

Ramgoolam has strong affinity for India. During the Covid-19 pandemic, when he was critically ill, he was brought to Delhi for treatment, and he duly thanked India after his recovery.

Early this year, India inaugurated a new airstrip and jetty on the Agalega island of Mauritius. With this upgrade of the existing 800-metre airstrip into a full-length airfield, India can station and deploy these large carriers directly on the island, providing security in the region.

Further, as part of the Modi administration’s “Security and Growth for All” policy, in addition to the upgraded airstrip, India plans to construct a port near the existing jetty, set up institutions for intelligence generation and sharing, establish communication facilities, and install a transponder system to track ships navigating the Indian Ocean. These new infrastructures will reinforce India’s reputation as a maritime power and expand its influence in that region.

In July, Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar visited Mauritius, where he met with key Mauritian political leaders, including opposition figures Navin Ramgoolam and Paul Bérenger. Ramgoolam has strong affinity for India. During the Covid-19 pandemic, when he was critically ill, he was brought to Delhi for treatment, and he duly thanked India after his recovery.

Moreover, the 77-year-old Ramgoolam is no political newcomer; he is the son of Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, the founding father of Mauritius. Ramgoolam has also served as prime minister twice.

In recent years, Mauritius has strengthened its ties with China, notably signing a free trade agreement in 2019. Mauritius could significantly benefit from Chinese investments in the digital economy, pharmaceuticals, and traditional medicine sectors. In 2022, the Bank of Mauritius set up a Renminbi clearance centre, further elevating its economic diplomacy with China.

However, in parallel with China, Mauritius also maintained its strong economic relations with India. Just one month after the China-Mauritius free trade deal came into effect in February 2021, Mauritius signed a Comprehensive Economic Cooperation and Partnership Agreement with India.

Additionally, with the UK transferring sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago back to Mauritius, India’s role as Mauritius’s strategic partner becomes even more significant, bolstering maritime security in the region and countering any aggressive action by China.

So, despite the change in government, there is hope that the bilateral relationship between India and Mauritius will remain strong. It remains a close watch.