On 20 May, India’s government notified the World Health Organisation of a confirmed outbreak of Nipah virus in Kozhikode, a district in Kerala, after test samples examined by the National Institute of Virology in Pune. By the end of the month, 19 cases of the disease had been reported, where 17 of them succumbed to the deadly virus.

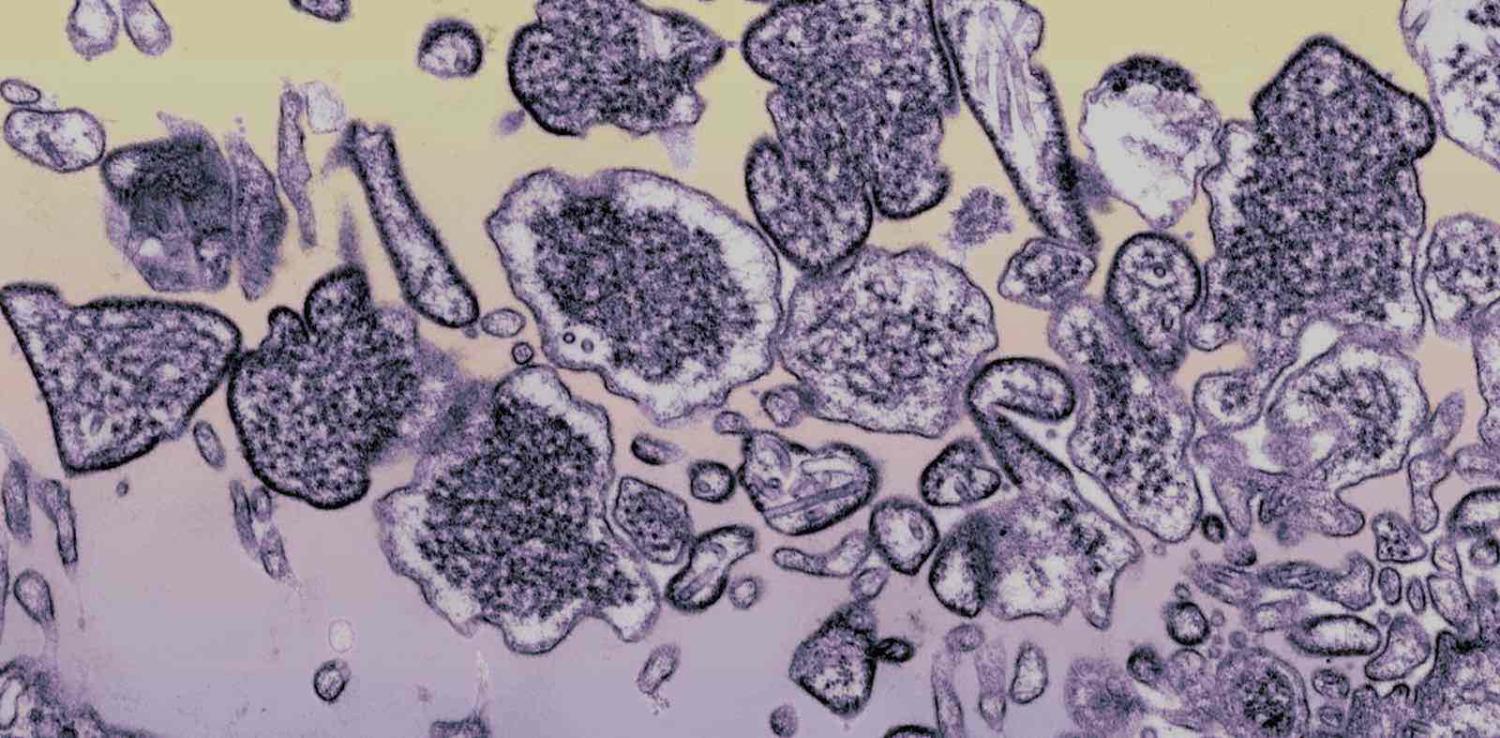

Nipah virus, which can damage the brain, was first isolated in the 1990s following an outbreak in Malaysia. One doctor, A. S. Anoop Kumar, head of the critical care department at Kozhikode Baby Memorial Hospital, described its symptoms:

When I initially examined the patient, his blood pressure and heart rate were high, and his health condition started rapidly deteriorating irrespective of the intensive care management. On further probing the history of the patient, I understood that three more members of the patient’s family had similar symptoms.

In India, the majority of cases occurred among those in close contact with the first victim, or patient zero, and further transmission of the virus was contained within two weeks due to the swift response of central and state government authorities.

Swift action

Before the outbreak was confirmed, the Kerala state Health Minister, K. K. Shylaja, commenced coordinated efforts between state health departments and private hospitals. A slew of services were initiated, including a new helpline for tracing contact.

More than 2500 people who had been in contact with the 19 infected patients were subsequently isolated; special ambulances and hospitals were equipped with quarantined cells; and financial reimbursements were issued to Nipah virus patients. In addition, thousands of tablets and antiviral medicines were imported from Malaysia, following offers of help from countries including Australia.

In 2009, the flu pandemic, or H1N1 outbreak, jolted India, resulting in more than 1400 reported deaths. The experience delivered some hard lessons, and an effort to revamp labs and other facilities to contain influenza was begun.

Private hospitals were given the lead role in containing the flu outbreak because government facilities were scarce. This public–private collaboration also occurred during the Nipah outbreak.

Arun Kumar, a virologist with Manipal Centre for Virus Research, told me the links established in Kerala following the 2009 flu pandemic in India greatly improved its health systems:

Those investments are paying off during the current outbreak, as the government and private hospitals could act swiftly in tackling the menace, cutailing the death toll to 17.

Over two weeks of perseverance and hard work, the Nipah virus was contained, and no new cases have been reported since 30 May. However, the area cannot be declared Nipah-free until, according the WHO guidelines, 42 days have passed since the last recorded case. But Kumar was insistent: “There is no need to panic.”

Traditional and social media failure

Despite the gargantuan government efforts, some practitioners of alternative forms of medicine made conflicting statements in social media, even casting doubt over the existence of Nipah virus.

This confusion was compounded by a string of statements on social media declaring that “fruits” were a vehicle for the virus. This led to the shutdown of fruit shops not only in the virus-affected district but also thousands of kilometres away in Hyderabad, leading to huge losses for farmers and vendors.

Distorted media statements led to other countries banning Kerala fruits, even as experts confirmed consumption of the fruit was safe.

Previously, there were concerns that remnants of fruit partially consumed by fruit bats led to the outbreak, as occurred in Bangladesh in 2004. Yet it was later confirmed that in this instance bats were not responsible for transmitting the virus.

Certain media organisations usually regarded as credible and ethical subverted the credibility of the government. Even in early June – a week after the last reported case, and with no new cases discovered – some media organisations were discussing which other countries were likely to be affected by Nipah virus.

Shoddy reporting only created fear and trepidation when the government had already taken steps to quarantine the patients and their close contacts. Chellenton Jayakrishnan, a neurologist at Kozhikode Baby Memorial Hospital, told me that unlike other viruses, such as swine flu, Nipah virus does not transmit extensively:

It usually gets transmitted to people who are having close contact, like the caregiver or patient’s relatives, without proper personal protection equipment, like a mask, gloves, etc. The lack of awareness regarding the Nipah virus has triggered new cases. But now it has been contained. The public at large needs to be alert, but there is no need for panic.

Yet the media games had a profound effect on the public, with many people taking to wearing masks in the streets after authorities had already declared that only people in close contact with the patients required protection. This continued even after 14 June, when the remaining Nipah-affected patients were discharged.

Media exaggeration and misreporting about Nipah virus only hindered progress made by the government and medical community. The experience stands again as a warning that during an outbreak, bad information can be just as dangerous as the virus itself.