Review: Crosswinds, by Vijay Gokhale (Penguin Random House India, 2024) and To Raise a Fallen People, by Rahul Sagar (Columbia University Press, 2022).

India’s role on the international stage has gradually expanded over the last two decades. Understanding this country of multitudes calls for diving deep into its history. Two recent books have helped me do just that.

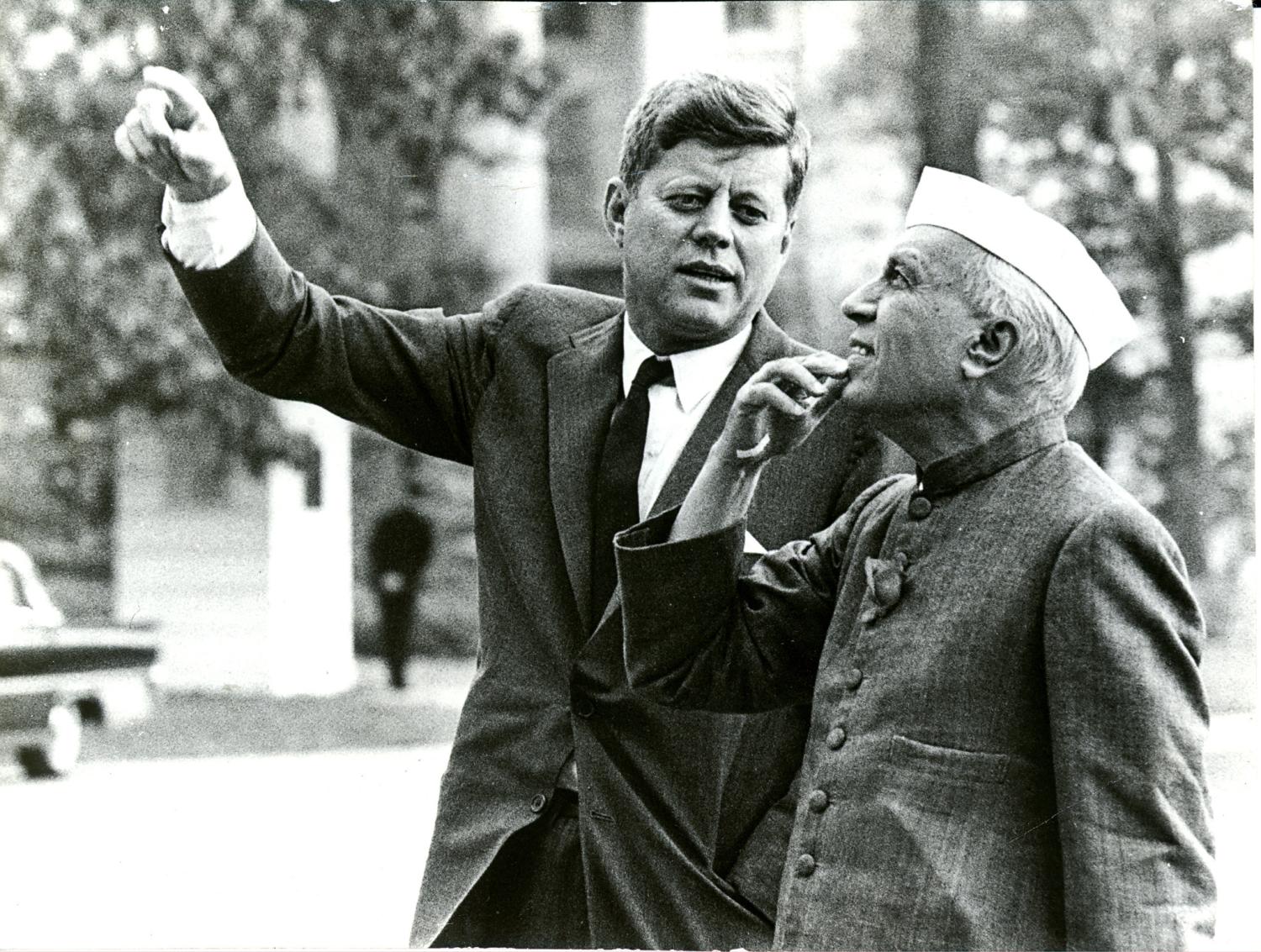

If you think the future of the Indo-Pacific will revolve around the machinations of its principal protagonists – China, India and the United States – pick up Vijay Gokhale’s Crosswinds. Gokhale is from that sparse breed of retired practitioners who marry academic rigour with precise prose. He retired as the Foreign Secretary of India in 2020.

Gokhale’s latest book paints a clear landscape of the turbulent decades in East Asia after the Second World War. The motivations of the primary players – the UK, US, China and India – are diverse. Some intersect, and many diverge.

For example, Churchill and Eden sought to reclaim British colonial possessions in the Far East. The lure of commerce drove them towards accommodating communist China. On the other hand, Truman and Eisenhower wanted self-government in the colonies, thinking incipient regional forms of nationalism would act as bulwarks against communism. In other words, while London was nostalgic about the pre-war East Asian balance of power, with Beijing giving it a free hand in Hong Kong, Washington wished to erect a new security order with a surer footing in Formosa.

China under Mao and Zhou played the long game. It coyly leveraged India’s over-enthusiasm for Asianism, the idea that India and China are natural partners against Western players, for their ends. They even poked the United States at regular intervals, teasing and testing its commitments in the Pacific. The communist leadership stood its ground when national interest demanded. For example, due to the firm red lines outlined by Mao and Zhou against Taiwanese misadventure, US Secretary of State Dulles put a lid on Chiang Kai Shek's zeal during the second Taiwan Strait crisis in 1958 when tension was about to spill over.

For its part, newly independent India laboured under the illusion that anti-colonial sentiment was more potent than strategic interests. Moreover, the diplomatic jockeying of Nehru's chief diplomat VK Krishna Menon led to bungling and severe credibility erosion. The net result was distrust from all sides. The principal players at the 1954 Geneva Conference on resolving the Indo-China question all had concerns about Menon.

Crosswinds comes after Gokhale’s three irresistible expositions on India-China relations. He started publishing when Indian public interest in China exploded after the recent dive in bilateral ties. In cricketing terms, Gokhale’s work would qualify as masterly centuries. Right from the middle of the blade. Exquisite timing.

The other book that gripped me recently is an anthology named To Raise a Fallen People, edited by the formidable scholar Rahul Sagar. It is a collection of long-forgotten essays and extracts from periodicals published in nineteenth-century India. Sagar’s painstaking collection of these writings dispels the notion that Indians in the nineteenth century were nativist folk engaged in domestic firefighting. Thanks to the gradual expansion of the English language and vernacular education, Indians of sufficient means devoted ample thought to questions of international affairs.

The works compiled in Sagar’s anthology are evidence of the rancorous debate among Indians on international questions. Issues of free trade, racism, English education, and geopolitical wrangling in not-so-distant lands stimulated nineteenth-century Indians with a global outlook.

Allow me to give you a sneak peek into the volume, to an episode with subversive potential given the ongoing war in the heart of Europe. The author of the curiously titled essay Why Do Indians Prefer British to Russian Rule? sings paeans to British values of liberty while rubbishing Russians as “slaves of a military caste”. To put this argument in context, imperial Russia expanded into modern-day Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in the 1870s, so many late nineteenth-century Indian intellectuals feared Russian designs over India. These writers chided the “masterly inactivity” school of British strategy and wanted London to take India’s security seriously. This group of Indian thinkers even started rallying public opinion in British favour when they came to know of Russians marching to take control of Herat in Afghanistan.

Now, put this episode in today’s context of Delhi’s relationship with Moscow, which is still governed by diktats of geography, principally the necessity to maintain a balance in the Eurasian continental theatre. In our times, Delhi does not fear an onslaught from Moscow. It therefore has the space to maintain cordial relations with Russia, unlike in the 1870s. Simply put, when countries have skin in the game, they tend to pursue their interests.