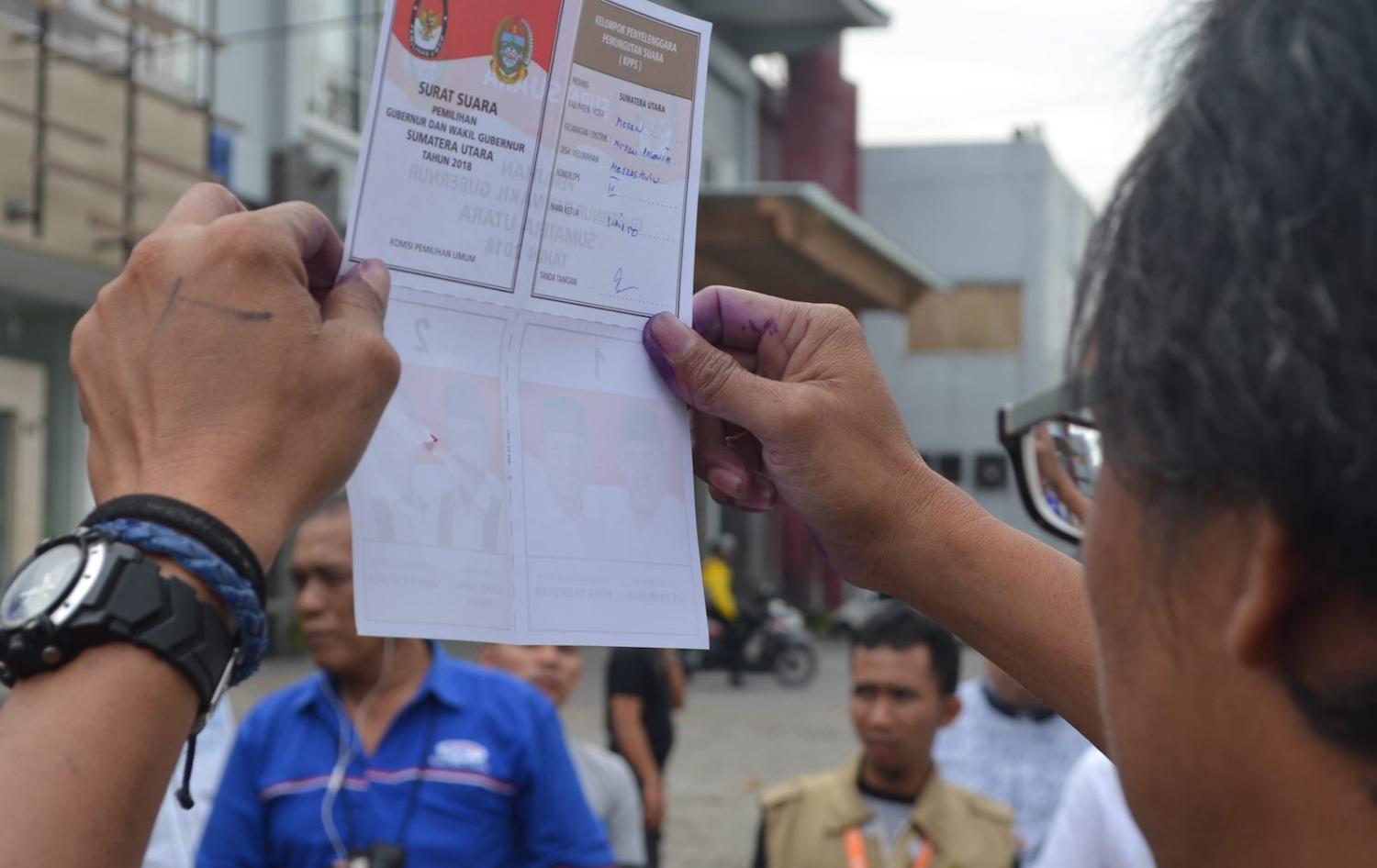

Regional elections took place across Indonesia on 27 June, when local voters went to the polls to elect governors, regents, and mayors. The results offer a fascinating insight into the current political landscape, albeit one that analysts need to approach with caution.

It is always tempting to look at regional elections in Indonesia as electoral tea leaves, used to extrapolate meaning in the run-up to the race for the presidency that will take place in 2019. I watched the hard-fought elections in North Sumatra – featuring Djarot Saiful Hidayat, one-time governor of Jakarta, running against military man Edy Rahmayadi, born in Sabang in Aceh province – closely, from the day Djarot took to the campaign trail at Cafe Sobat in the capital city of Medan to the evening of his crushing defeat in late June.

Analysts should be wary of using these elections as a guide in the race to the presidential palace.

From my days on the campaign trail, which took me from Medan to Karo Regency and down to Lake Toba, it seems fair to say that the latest round of elections won’t tell us much about whether current president Joko “Jokowi” Widodo is likely to win a second term, or if another hopeful, such as Prabowo Subianto, who ran unsuccessfully in 2014 and is expected to try his luck again, may snatch victory.

Regional elections in Indonesia are far more complicated than simple party politics.

For example, in North Sumatra, often overlooked in electoral analysis but a significant voting power as the fourth largest province in Indonesia, it was a win for Rahmayadi with 57% of the vote, and a loss for Djarot representing Jokowi’s Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P). This could seem to augur badly for Jokowi in 2019, but North Sumatra has long been a stronghold of parties other than PDI-P. The outgoing governor, Tengku Erry Nuradi, represents the National Democratic Party (Nasdem) which threw its support behind Rahmayadi.

Couched in those terms, Djarot’s defeat is not much of a surprise, and the results not particularly significant ahead of the presidential elections. Voters went with the status quo rather than the regional opposition, as would be expected.

Put in wider context, Jokowi actually won the majority in North Sumatra in the 2014 presidential elections, with 55% of the votes against Prabowo. So a win for Rahmayadi doesn’t necessarily mean a win for a presidential opposition party candidate in 2019 either. Regional politics doesn’t always translate to national voter trends in Indonesia. If it did, North Sumatra should have been an easy win for Prabowo back in 2014.

If we look at elections in Indonesia through the prism of North Sumatra, then primordialism is alive and well. While Djarot is Muslim, his running mate Sihar Sitorus is a Batak and also a Christian, and it was no surprise that the pair won the majority of votes in places such as Lake Toba, a predominately Christian area.

Both Djarot and Rahmayadi also sought to curry favour with local Batak (an ethnic subgroup native to North Sumatra) voters by “adopting” traditional Batak surnames, or marga, although neither man is ethnically Batak. Rahmayadi took the name of the Ginting clan who mostly live in Karo Regency, and Djarot was bestowed with the Nababan surname of the Batak Toba.

Yet Karo Regency, a majority Christian area, voted for Djarot and Sihar rather than Muslim candidate Rahmayadi. These voting markers around ethnicity and religion, while interesting as part of regional analysis, translate less easily to the presidential elections, as Jokowi and possible opponents, such as Prabowo, are both Javanese Muslims.

North Sumatra does make for an interesting case study into voting habits across Indonesia. Data from the General Elections Commission (KPU) shows 9 million registered voters in the province, yet only around 1.6 million actually exercised their right to vote. This kind of voter apathy is often seen at regional levels across Indonesia.

Yet voter turnout is much higher for presidential elections. Asia Foundation findings revealed that more than 6 million North Sumatrans took to the polls in the presidential elections, amounting to a 75% voter turnout across the archipelago.

But data in regional elections in Indonesia is skewed by low voter figures in some areas. Projecting a win for either Prabowo or Jokowi based on 1.6 million regional voters in a province of 9 million is simply impractical.

While the regional elections in Indonesia provide opportunities for colourful analysis at a district level, they serve as a shaky predictive tool for what may lie ahead in 2019. Analysts should be wary of using these elections as a guide in the race to the presidential palace.