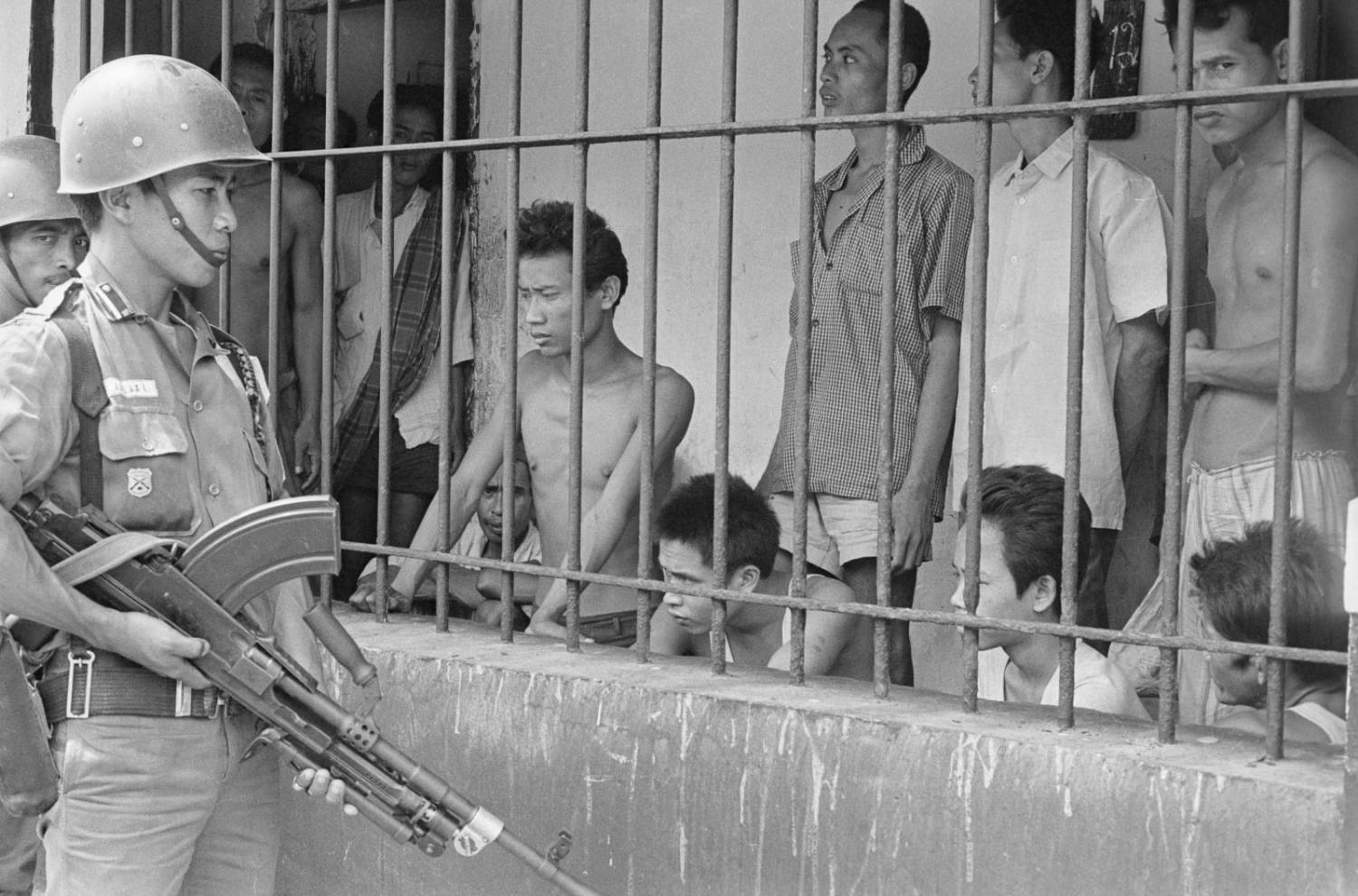

The civilian witness held a pressurised kerosene lamp. He stood just a step back from the edge of the mass grave, two meters deep. Thirty-one men, purported members and companions of the Communist Party of Indonesia, were condemned for midnight execution. They were made to sit on the edge of the pit facing inward. An army detail shot the victims. Blood and brain parts splattered on the clothing of the witness.

The multiple executions took place in the island of Sabu, Sawu in international maps, in East Nusa Tenggara province on 29 March 1966.

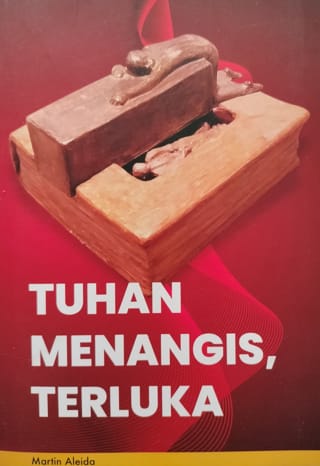

The above narrative is drawn from a written eyewitness account in the 2023 book Tuhan Menangis, Terluka (God Weeps, Hurt). The title derives from a line by Mery Kolimon, a church minister and writer in eastern Indonesia who laments the pain of victims of violence.

God Weeps is a compendium of accounts of crimes against humanity in Indonesia carried out across 1965–66. The book was compiled by Martin Aleida, an accomplished and prize-winning short story writer, himself at one time a political prisoner in a Jakarta military detention camp. His crime? In 1964–65 Martin was a reporter for the Harian Rakjat, People’s Daily, organ of the Communist Party of Indonesia, or PKI.

The 598-page volume groups stories from victims of human rights abuse, as well as their families, affected by the 30 September Movement. This was the coup attempt in 1965 that the Indonesian army command blamed on rogue left-wing officers and the PKI. The PKI was Indonesia’s most potent political party, claiming three million members, which was seen as a challenge to the army for power.

Hundreds of thousands of people connected to the PKI and its affiliate organisations but having had nothing to do with the 30 September Movement were tormented, physically abused, imprisoned without trial, and murdered.

Much has been written about the massacres in Central and East Java. This book takes material from other writing, letters and documents to explore what took place beyond Java as well. Of particular focus are the islands of East Nusa Tenggara, a Christian majority province about 1900 kilometres east from Jakarta, including Kupang, the provincial capital.

“I feel shame to be part of the generation of the actors of this crisis,” Ben Mboi, the late former governor of East Nusa Tenggara and army general, told Aleida. In that context, Aleida’s book exposes the dark pages in Indonesia’s history, a self-reproach for the nation not to suffer amnesia and repeat such atrocities.

Absent from the book is a critique of what the Indonesian government has done or not done since relating to the 1965–66 massacres.

This stain on the nation’s history was put under the spotlight in an important hearing at The Hague in November 2015, which allowed survivors to give testimony. In apparent response, the Joko Widodo government in April 2016 held a two-day symposium in Jakarta on the 1965 tragedy. The symposium allowed victims and actors to speak and was the first time the government had allowed public scrutiny on a deeply divisive subject.

Survivors of the anti-communist purge continue to live with a stigma. Up to then, they had been reluctant to meet and talk openly about their less than equal civil status for fear of being accused of aiming to revive the PKI. But while the symposium called for reconciliation and redress for the victims, one of the organisers, then minister Luhut Binsar Panjaitan, ruled out any government apology.

On 11 January this year, Jokowi, as the president is known, acknowledged in a televised statement that the 1965 events were a travesty of justice, one of 12 gross violations of human rights he said had occurred in Indonesia from 1965 to 2003.

“With a clear mind and a sincere heart, I, as head of state of the Republic of Indonesia, do acknowledge that gross violations of human rights did take place in numerous events,” Jokowi stated solemnly.

Jokowi vowed that no gross human rights violation will occur again in Indonesia. No other leader in Southeast Asia has made any similar public declaration.

Last month, he travelled to Rumoh Geudong, Aceh province, a site of torture of locals by military personnel in a 1989 regional conflict. Jokowi launched a range of non-judicial settlements over major human rights violations. The government’s resolutions include the restoration of civil rights of victims and family members, including a return from overseas exile, a monthly cash allowance, and benefits in health, education, food and housing. Similar launches are to take place in five other sites where tragedies took place: Lampung, Palu, Wamena, Semarang, and Jakarta.

Coordinating minister for political, legal and security affairs Mohammad Mahfud Mahmodin underscored that a non-judicial settlement does not rule out the right of survivors to seek justice in court. Human rights activists have welcome the government’s action but lament it does not go far enough. Government policy compensates the victims, but does not prosecute the perpetrators of the human rights abuse, who should be made accountable by judicial process.

And in another shortcoming, the government has made no apology to the victims.

Jokowi had pledged action on human rights when running for election. He has more work to finish before his term as president ends in October 2024.