Italian-American physicist Enrico Fermi was having lunch with his colleagues in 1950 when he asked a now famous question: where is everybody? He was referring to the apparent contradiction that, despite the mathematical probability that humans should have seen evidence of intelligent extra-terrestrial life already, none had.

One prominent hypothesis to explain this “Fermi paradox” supposes that somewhere along the path from planetary formation to abiogenesis (the arising of life from non-living matter), to the evolution of intelligent life and to interstellar exploration, there is a “great filter” that has proven virtually impenetrable across space and time. This “probability barrier” could lay in humanity’s past, overcome against all odds when life originated billions of years ago. Or it could lie ahead.

Philosophers in the field of existential risk identify several types of threats that could constitute the great filter, insofar as they would permanently destroy humanity’s long-term potential (if not render humans extinct). Taken individually, many of these are low probability, naturally occurring events such as an asteroid strike, a super-volcanic eruption or a nearby stellar explosion. There isn’t much we can do about risks like that.

The silver lining of climate procrastination could be that it serves as a wakeup call for action on existential risk.

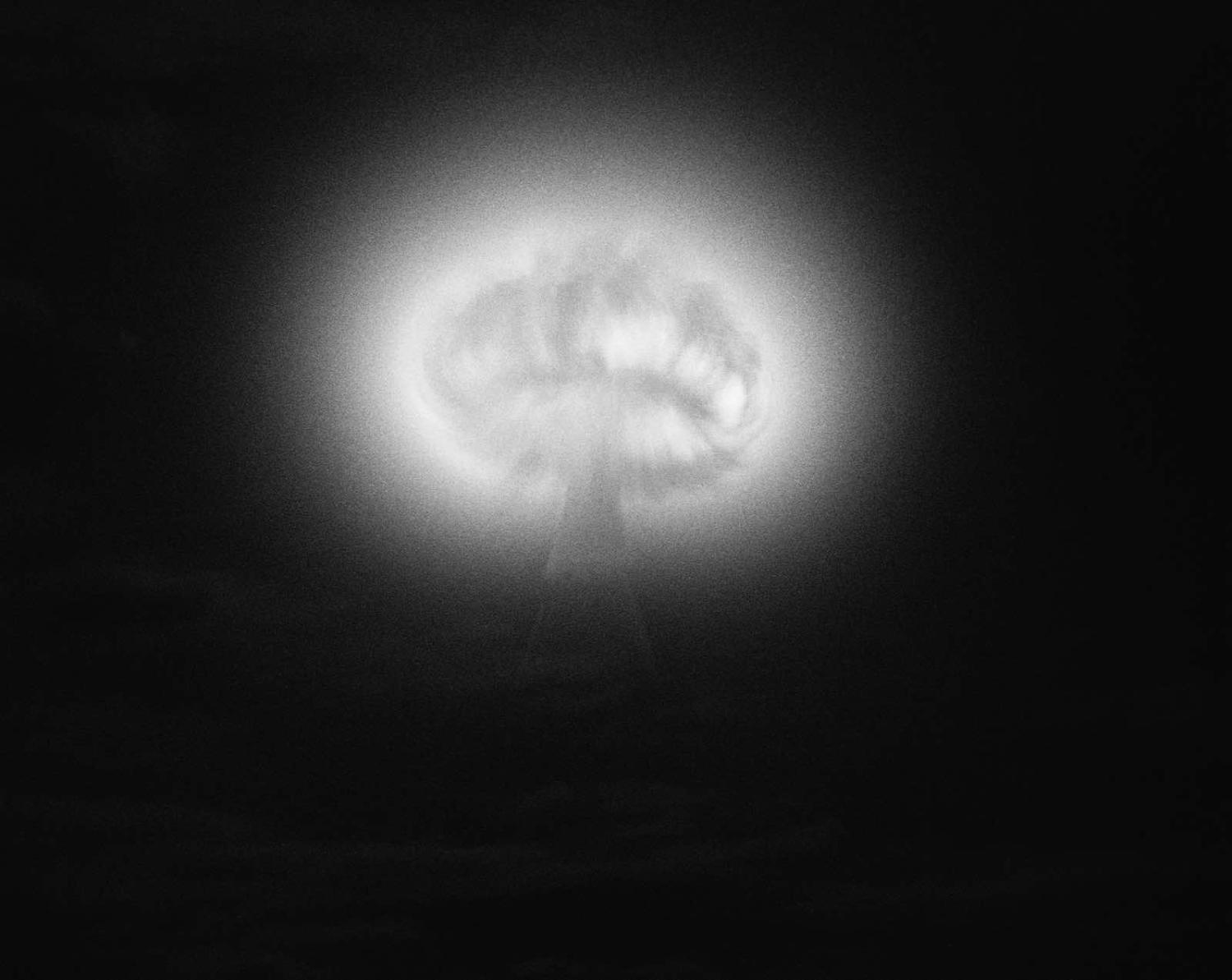

But we have much more agency when it comes to anthropogenic existential risks – such as nuclear winter, engineered pandemics and non-aligned artificial intelligence – because they have only recently become possibilities as a consequence of humanity’s rapidly growing power and capability.

The good news is that these types of risks are amenable to mitigation efforts; the bad news is that there is a higher likelihood that they will manifest. Never before has humankind possessed the ability to completely destroy itself. Philosopher Toby Ord believes that we are standing at the precipice, with a one in six chance over the next century that humanity’s potential will be irrevocably destroyed.

The existential nature of existential risks means that we cannot wait until one materialises and then draw lessons from our mistakes – by then it will be too late. With the stakes so high, we need to be proactive in our efforts to reduce the overall existential risk that we face to a more sustainable level. In the case of nuclear proliferation and climate change in particular, Australia must do better.

Take the recent AUKUS announcement, specifically the decision that would see Australia acquire nuclear powered submarines. This would exploit a loophole in the International Atomic Energy Agency system whereby nuclear material utilised for submarine propulsion is exempted from inspection. It is highly unlikely that Canberra intends to siphon off fissile material for a bomb, but the precedent it sets would nevertheless weaken the global nuclear non-proliferation regime over time.

Nuclear weapons are not going to disappear overnight, but decisions should be taken that move us toward a world free from their scourge, rather than further entrenching them. Accidents and miscalculations happen, and it is exceedingly unlikely that a Vasili Arkhipov or Stanislav Petrov will forever be on hand to avert catastrophe.

In terms of climate change Australia is at best a laggard, if not a pariah. The Coalition government’s glacial movement towards a belated adoption of a net zero emissions target by 2050 comes as the global conversation shifts to 2030. Narratives of a “new normal” are misguided – the bushfires that Australia experienced in late-2019 and early-2020 do not signify a new ecological equilibrium as distinct from the old. Climate change is dynamic, and the risks it poses will move from catastrophic to existential if emissions aren’t reigned in swiftly, particularly as tipping points are reached and feedback loops triggered.

The climate crisis is far from over, but the slowly shifting narrative and incremental movement towards action shows that, while not yet sufficient, progress is at least possible on what is at its core a global commons issue. The silver lining of climate procrastination could be that it serves as a wakeup call for action on existential risk. A recently released United Nations report that includes a section on catastrophic and existential risk stated that “the cost of being prepared for serious risks pales in comparison with the human and financial costs if we fail”.

Australia should heed that message and at minimum start the conversation. The stakes couldn’t be higher.