In the months leading up to his dramatic return last year as Malaysia’s Prime Minister, Mahathir Mohamad had positioned himself as a strident critic of his predecessor’s approach to China. Mahathir went so far as to accuse former prime minister Najib Razak of selling Malaysia’s sovereignty to China, particularly over the much-analysed Belt and Road Initiative. In some of his first acts after taking back the top job, Mahathir suspended several China-backed mega projects against claims they would leave future generations of Malaysians in unreasonable debt.

He went further, too, casting aspersions on China as a new colonial power and warned the Philippines about the dangers of falling into China’s “debt-trap” diplomacy. It all appeared fitting with a popular local mood.

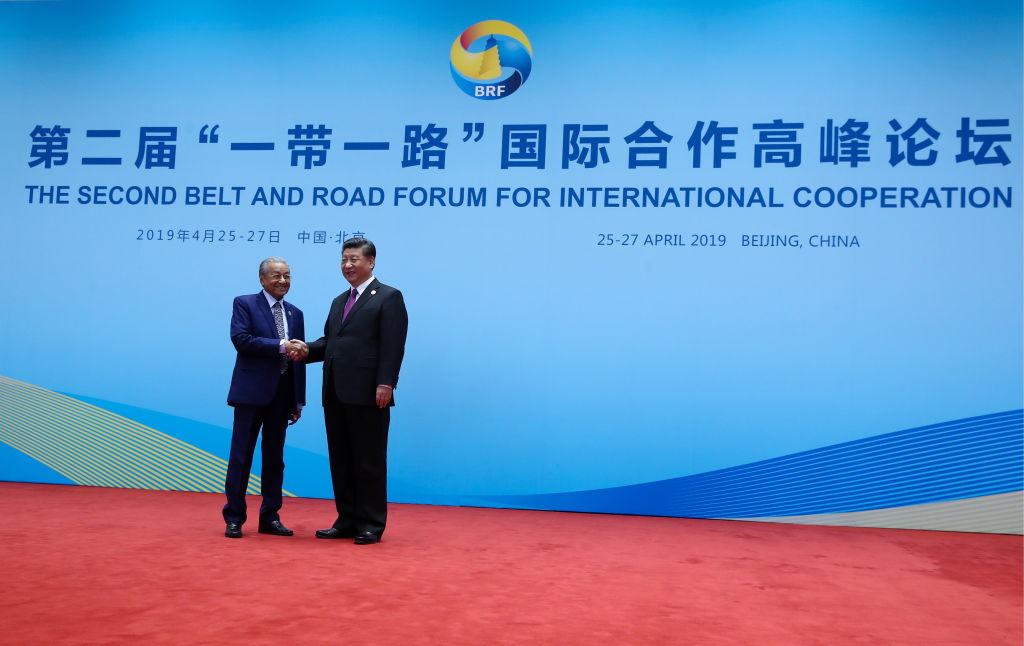

Yet there was Mahathir in April, in Beijing as a guest of China’s Xi Jinping at the second “BRI Summit” with counterparts from across the region, pledging his “full support” for China’s vision.

What explains Malaysia’s somewhat circuitous route to participation in the BRI?

Partly this was a product of re-negotiation. The East Coast Rail Line (ECRL) was one of the megaprojects signed under Najib. Shortly before the BRI Summit, Mahathir claimed that by re-routing the line to do away with a proposed tunnel under the Titiwangsa mountains, it would save Malaysia US$5 billion. (Abandoning the ECRL would have reportedly incurred a cost of about the same amount in cancellation fees.)

Another mega project, Bandar Malaysia (Malaysian Township), which was also initiated by Najib, had also come under scrutiny. Again, just before the BRI Summit, Mahathir conceded he had mistakenly believed the project only benefitted China. As he now tells it, many domestic companies are involved in the project to their benefit, so he will allow Bandar Malaysia to go ahead.

But beyond the specifics in each project, Mahathir’s new-found confidence in China’s BRI has implications for the region.

Mahathir remains a critic of China’s approach to disputed territory in the South China Sea, but at the very least, having him drop his invective about the BRI will help ensure less regional opposition.

For one thing, Mahathir is an elder-statesman, so his implicit support offers China a chance for a firmer regional footing. Mahathir remains a critic of China’s approach to disputed territory in the South China Sea, but at the very least, having him drop his invective about the BRI will help ensure less regional opposition.

Second, Malaysia’s strengthening relationship with China might rub against the US’s Indo-Pacific strategy. As Mahathir sees China as an economic superpower with great benefit for the Malaysian economy, there is no reason why he would want to be actively involved in a US strategy seen as an effort to contain China’s sprawling influence.

Third, there is an economic consequence, particularly around trade talks. Malaysia has been a big proponent of the centrality of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, so it is only natural that Mahathir would want to put his support in trade talks behind the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), where ASEAN is key.

The RCEP may not be signed anytime soon, but Mahathir is not likely to want to see its demise. RCEP could further facilitate China’s presence in Malaysia as an investment hub for the region. With the US-China trade war, Malaysia could be an export hub for products made in China, but with sufficient local content to overcome objections due to rules of origin.

This ties to a fourth issue. Under Mahathir’s leadership, Malaysia will have its doubts on the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). But this has nothing to do with Malaysia’s new found proximity to China. Mahathir has always had doubts about the US, and Trump’s indecisiveness has not been appealing to the Malaysian leader. In fact, Mahathir had opposed the TPP, and with the US out of the equation, there is less reason to ratify the agreement, especially if the CPTPP is thought to be about containing China. On the substance of the deal, the government is disturbed by issues such as intellectual property rights, investor state dispute settlement and government procurement.

So unlike Najib, who had warm ties to the US while reaching out to China, Malaysia’s tilt to China under Mahathir will mean less support for the US’s initiatives in the region. Not all of this will be a result of China – Mahathir has his own views and domestic considerations – but he will no longer be a strong voice against China’s new colonial tendencies or the dangers of China’s debt-trap diplomacy. In that sense, the world may have lost its last non-aligned leader.