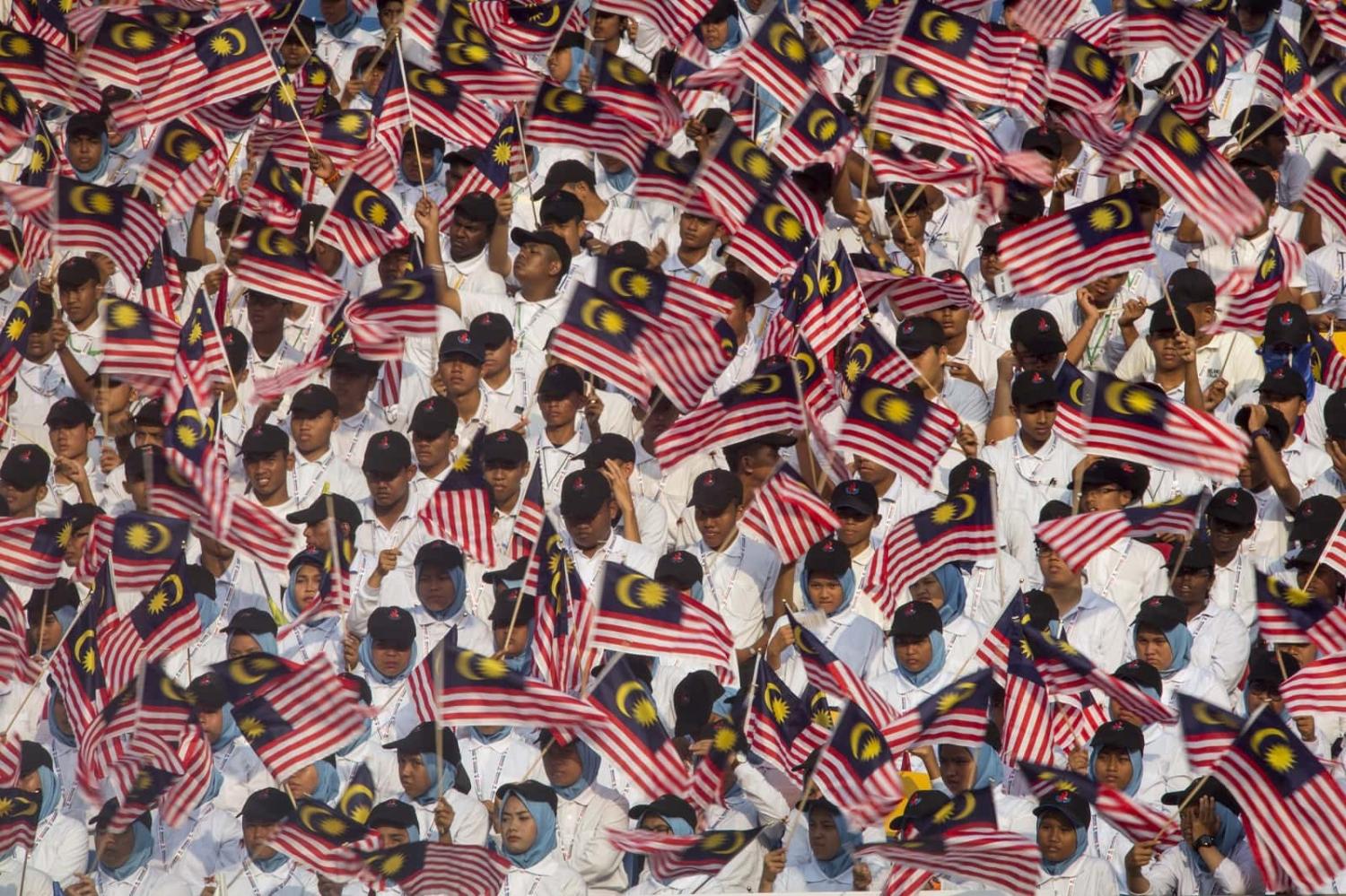

On 16 September, the Federation of Malaysia – a country widely regarded as a Southeast Asia success story – will celebrate its 60th anniversary. While neighbours such as Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines have suffered military coups and a heavy toll from civil strife, Malaysia has only experienced one episode: the 13 May 1969 ethnic riots.

Back then, after order was restored, the political structure was revamped into a system based on Ketuanan Melayu (Malay Supremacy). This led to a long period of stability under the Barisan Nasional coalition, especially the years under the strongman Mahathir Mohamad, who ruled from 1981 to 2003. The system fell apart in 2018 when Mahathir, having come back from retirement, led the opposition to overthrow the BN. Remarkably, aged 93, he returned as prime minister from 2018 to 2020.

In November last year, after an inconclusive election, Anwar Ibrahim, long seen as a “Muslim democrat” by the West, was asked by the King to form a coalition government. The present two-coalition arrangements in Malaysia consist of Anwar’s Unity Government (Pakatan Harapan + BN + Borneo parties) and the opposition Perikatan Nasional (Bersatu, Parti Islam Se-Malaysia and Gerakan).

The biggest takeaway from the November 2022 election was “the Green Wave”, or the rise of political Islam and Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS). PAS is now the largest party in the Malaysian parliament with 49 seats. The second-largest party in parliament is the Democratic Action Party (DAP), a Chinese-based party representing the non-Malays, with 40 seats.

While many politicians argued that the Green Wave was either not real or a one-off phenomenon, it may indeed reflect a significant shift in Malay politics. More and more Malays, especially in the younger demographic, are backing arguments that Malaysia’s future lies in PAS’ vision for the establishment of a Malay-Islamic state.

This was confirmed in the recent 12 August state elections, held across six states on the Malay Peninsula. The results indicate that PAS not only retained the Malay votes captured in November 2022 but increased their overall support by about 5-7 per cent among the Malay voters. In a remarkable display of PAS power, all the seats in the Terengganu state assembly were won by PAS, while in the neighbouring Kelantan state, PAS won all but two state assembly constituencies. Terengganu and Kelantan are seen as Malay heartland states.

The next general election is due in 2028 but likely to be held earlier. Whether these latest state results mean that Perikatan Nasional (and PAS) will inevitably win is still up for debate. But what is clear is that Malaysia’s politics is now fragmented over a vision for the country.

Three distinct views are competing.

The most support appears to be for the idea of a Malay-Islamic state espoused by PAS. It is clear the Malay polity is backing the PAS mantra that Malaysia must be under the rule of Islam and Malays, and that the non-Malays must never hold political sway. The November 2022 general elections and the recent August state elections confirmed support for this view.

Hadi Awang, the PAS leader, has openly said many times the non-Malays must be “grateful” for being allowed to stay in Malaysia, and in a bizarre attack, said the non-Malays are the main source of corruption. If his words are taken literally – i.e., the political system can only be in Muslim hands – then non-Malays would be regarded as “dhimmi”, meaning non-Muslims residing in an Islamic state. Often translated as “protected person” under a view of political Islam, a dhimmi does not have the same political rights as Muslims and is required to pay a special tax to maintain their protected status. Property, life, and the right to practice other religions are among rights that come with this status, but not full political rights.

The second vision for Malaysia is the one espoused by the DAP, who won all but one of the non-Malay seats it contested in the August state polls, thus confirming its status as the political voice of the non-Malays. DAP’s vision for Malaysia can best be described as “moderation” or the “middle path” – meaning that while Malaysia is largely a secular country, Islam remains the de facto official religion, with non-Muslims not subject to Islamic laws and still able to play a substantive role in the political process, including holding cabinet positions, although not the prime ministership. The state will respect the non-Islamic religions and allow the minorities a free hand in the economy.

The third vision for Malaysia comes from the Borneo states, Sabah and Sarawak. Most analysts of Malaysia forget the “Borneo bloc” is now crucial for anyone who wants to form the federal government. Since the 2008 general elections, MPs from Borneo have offered the numbers needed to form the federal government. Their vision is that political Islam does not apply to the Borneo states and that there is freedom of religion. They accept the phrase used in the Constitution of Malaysia, that “Islam is the religion of the federation”, but argue this does not apply to them since it was stated clearly in the 1963 Malaysia Agreement that there will be no state religion in Borneo. They also want a high degree of autonomy and, if possible, no interference from the federal government on anything to do with Sabah or Sarawak affairs. In other words, they are almost a “state within a state” in the Malaysian federation. This sees two Malaysias with vastly different characters: Malaya and Sabah and Sarawak, divided by the South China Sea.

After 60 years of the federation, and with much success to celebrate, still national unity and national identity are missing. With three very distinct visions for what Malaysia should be, the future of the federation will be anything but smooth.