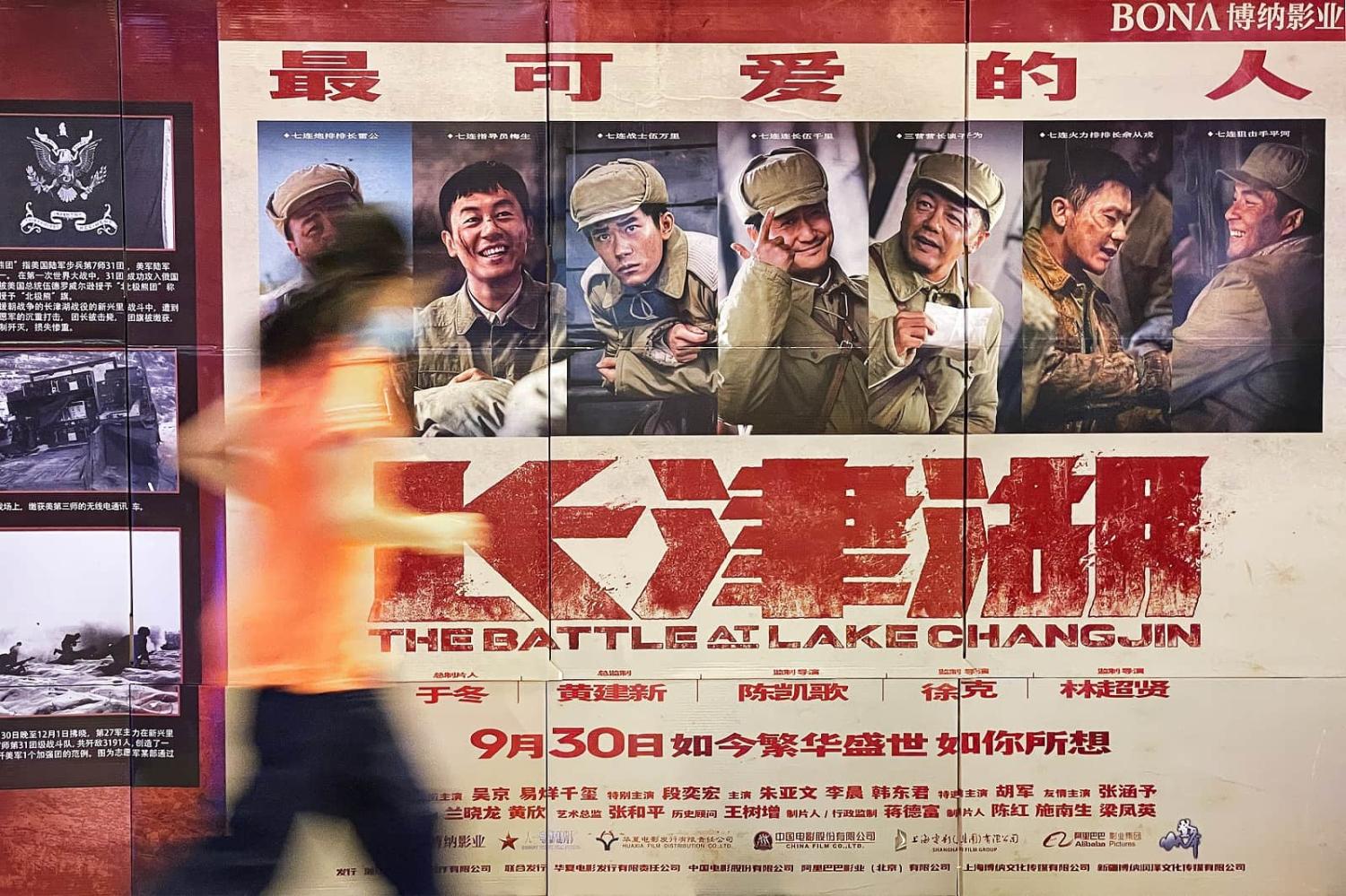

Every country has its national myths – the beliefs and narratives that serve as the foundation of its national identity. These myths find expression through a nation’s culture. A perennially popular form of this is cinema, and the most potent is the propaganda war film. In the last year or so, America, China and India have each released blockbuster films with strong nationalistic themes, Top Gun: Maverick, The Battle at Lake Changjin, and RRR. Each has become massively popular with audiences, Maverick the highest grossing film in 2022, Lake Changjin the highest grossing Chinese and non-English film of all time, and RRR the third highest grossing Indian film and second highest grossing Teluga language film of all time.

All three films share the common characteristics of nationalistic war movies: the importance of brotherhood, the nobility of sacrifice, nostalgia for an imagined past, limited and/or underdeveloped female characters, and unintentional homoeroticism – all those classic tropes proven for blockbuster success. Their massive popularity comes for the most part from being legitimately good films (in terms of action and spectacle, they are all almost perfect, in terms of writing … eh), but that doesn’t mean we should ignore how these films reach their domestic audiences by reinstating distinct nationalist myths.

Top Gun: Maverick, the sequel to the 1986 hit Top Gun, centres on Tom Cruise’s iconic character Pete “Maverick” Mitchell, a former United States Navy captain who is called in to return to flight school as an instructor to guide a new generation of fighter pilots through a mission to neutralise a “rogue state’s” uranium enrichment plant. Here, Maverick must prove he still has what it takes to be the best, while getting the new hotshots Hangman and Rooster to reach their full potential.

Labelling the movie propaganda has proved controversial in film circles. One half-star review on Letterboxd trashing the film as nationalistic jingoism went viral, causing outrage online. An argument could be made that the film is less about the glory of America and more about the glory of Tom Cruise, one of Hollywood’s last true movie stars. It is still hard to deny that the film could have the same effect as the original Top Gun, which lead to an increase in recruitment to the United States Navy (even if not as large as some boast). There is also the question of the involvement of American weapon manufacturers such as Lockheed Martin. Ultimately, the film harkens to a nostalgia for 1980s America.

The Battle at Lake Changjin, set during the Korean War, follows the 7th company of the People’s Volunteer Army. Led by Commander Wu Qianli (played by popular action star and frequent leading man of propaganda war films Wu Jing), the unit faces off against US forces in bloody conflict, culminating in a US retreat in the real-life Battle of the Chosin Reservoir in 1950. The most expensive Chinese film of all time, it was commissioned by the Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda department in 2021 as part of the 100th anniversary of the Party. With three directors, Chen Kaige, Tsui Hark and Dante Lam, the film is a massive spectacle of blood, carnage and extremely blunt nationalistic propaganda. So blunt that it is easy to understand why it has only found commercial and critical success domestically within China.

RRR is extremely loosely based on two real anti-colonial Indian rebels in the early 20th century, Alluri Sitarama Raju and Komaram Bheem. In this fictionalised tale, the two meet up during their own separate struggles against the British Raj and quickly form a strong bond, including the shared goal of fighting for Indian independence. The most expensive Indian and Telugu-language film of all time, it has become very popular in the West thanks to word of mouth from film critics and YouTubers who rave about the fantastic direction from S. S. Rajamouli, the grandiose action, and the heart-warming friendship between Raju and Bheem.

To understand how the films present distinct nationalistic ideals, it is worth looking at how they portray heroes and villains. In Maverick, the heroes are the individual fighter pilots, Maverick, Rooster, Hangman, each with their own personality and character arcs (something that Lake Changjin and RRR honestly lack). They are the quintessential American heroes who buck the system and kick ass.

In Lake Changjin, we follow a group of soldiers who are pretty much stock-standard war film stereotypes. We’ve got the brave leader, the young brash recruit, the cool-headed sniper, the wacky explosives expert. Lake Changjin does add a unique modern Chinese spin with the introduction of the political instructor, the Party official within the squad who acts as the heart of the company, keeping spirits up while reminding them of their purpose. Alongside this, there is a sub-plot following Mao Anying, the son of Mao Zedong (here in a Churchillian role). Anying nobly joins the fight and meets his end sacrificing himself to save important documents. The lack of characterisation can be seen as more than just lazy writing. Here, the true hero isn’t Wu Qianli or Mao Anying, or even Mao Zedong, it is the spirit of China, and that spirit is found in the People’s Liberation Army.

The champions in RRR are our two leads, Raju and Bheem, who are like superheroes from a Marvel flick. An unstoppable power or an immovable object, these forces of nature band together to fight for India! The film goes as far as to insinuate that Raju and Bheem are the reincarnations of legendary heroes from Hindu mythology, signalling the film’s uncomfortable relationship with Hindutva nationalism. It then delves into casteist themes as the relationship between Raju and Bheem changes from one of equals, to one where the lower-caste Bheem devotes his cause to the upper-caste Raju. He becomes subservient to Raju, and to an idea of Hindu Unity. This demigod-like character can be seen as symbolising the different sectors of Hindu nationalism, one supporting the other to fight for the Indian nation.

In RRR, the villains are British Imperialists, cruel jingoistic bastards who act so monstrously that it borders on caricature, till one remembers the reality of the British Raj. The film opens with a scene in which a British captain instructs a soldier not to shoot an Indian villager as it would be a waste of a British bullet. They look down upon our Indian heroes, insult their culture and intellect, and at times treat them like cattle or pests.

RRR and Lake Changjin also share the enemy’s trait of dismissing our heroes as being culturally inferior. However, in Lake Changjin the American soldiers are treated with surprising sympathy, their belief in cultural superiority coming across as a sign of ignorance. Thrust into a brutal war, the American soldiers serve as a worthy opposing force, whose subsequent rout by our Chinese heroes demonstrates that the strong and magnanimous People’s Liberation Army can defeat even the mightiest foes. This does not include General Douglas MacArthur, who is depicted more akin to a villain from a video game, a blood thirsty warmonger who seeks destruction upon North Korea and China (which was kinda true in real life). He is the devil who sends the American soldiers to war, underestimating that the Chinese troops are even braver.

And then there is the enemy in Maverick – the nameless, featureless “rogue” nation that threatens with its possible nuclear weapons. Its name is never spoken, and its pilots are only shown in stormtrooper-esque helmets that completely obscure their faces. They represent no one, just the enemy out there that threatens world peace and the international rules-based order.

The movies, they are good. Whether it is Maverick’s glorious cheese, The Battle at Lake Changjin’s cacophony of stylish bloody violence, or the magnificent operatic epic that is RRR, these are fine pieces of popular cinema that have reached massive audiences. That is not to deny their nationalistic roots, for by examining these we can see what drives these films. It also helps us understand how each country’s nationalism paints pictures of “self” and “enemy”. While not completely accurate examples of these nationalist myths, they are clear enough to inform others outside the country. Critical examination of the three films provides insight into these myths, as well as how they form the narrative. But most importantly, they are very fun to watch.