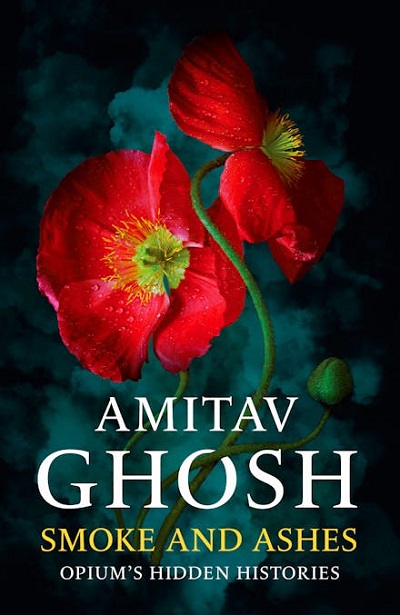

Book review: Smoke and ashes: Opium’s hidden histories by Amitav Ghosh (Murray, 2024)

Switching for a while from fiction to fact, Amitav Ghosh has written an account of “perhaps the oldest and most powerful medicine known to man”, an “opportunistic pathogen” named opium.

Opium, its trade and the wars that it caused, were the subject of Ghosh’s Ibis trilogy. Ghosh has now built out from his three-volume study of the ways in which Britain provoked three Opium Wars with China in order to smash Chinese trade restrictions, seize Hong Kong and addict much of China to a lethal drug. Some of the massacres, famines, pillaging and expropriation that disfigured the British Empire were more gruesome than the opium trade, but few were more sordid or insidious.

To supply a domestic market addicted to tea, and avoid draining silver bullion reserves to pay for those leaves, the British resolved to find a commodity for barter trade with China. Opium was the best bet. The British then boosted demand in China to meet supply created in India. War was an option of last resort, the British having proved unable to seize tea plants, steal the requisite technology or kidnap skilled workers.

Amitav Ghosh has written many wonderful novels, none better than the first in the Ibis set, Sea of Poppies. He has detoured from novels into non-fiction before, to present a fervent case on climate change. Here, Ghosh not only applies the meticulous, fine-grained research that underpinned the Ibis books. He deploys a novelist’s skill with colour and movement, emphasis and embroidery, to transform the opium story. The reader is offered a morality tale, a thoroughly documented history and a poignant remembrance of ruined lives in both India and China.

Ghosh is incorrigibly curious as well as deeply learned. Accordingly, his analysis ventures into biology and chemistry, “biopolitical conflicts” and doublethink, along with a novelist’s focus on motives and intentions. In addition to his Britain–India–China tale, Ghosh includes many anecdotes and appraisals of opium’s uses and abuses, past and present.

His book is certainly not a polemic; readers seeking a full-throated denunciation of the British Raj should consult Pankaj Mishra or Shashi Tharoor’s Inglorious Empire: What the British did to India. Nonetheless, Smoke and Ashes does present an astringent indictment of the “drug-pushing racket” and the “colonial narco-state” associated with that trade.

Along the way, Ghosh finds room to advise the reader that “hipster” derives from the posture of Chinese opium addicts reclining on one hip while smoking the drug. In the same whimsical but relevant way, Ghosh notes that, by the late eighteenth century, the East India Company was obliged by law to keep a year’s supply of tea always in stock – lest benighted British addicts were deprived of their drug of choice. More bizarrely still, given their current dependence on chai, Ghosh explains that “Indians were introduced to tea-drinking as an afterthought”.

Throughout, Ghosh’s narrative is underpinned by a remarkable command of apposite and striking detail, ranging from pecking orders among lascars to money flows in and out of Manhattan. All are designed to teach a “lesson about humanity’s limits and frailties”.

Main image courtesy of Unsplash user Bart Ros.