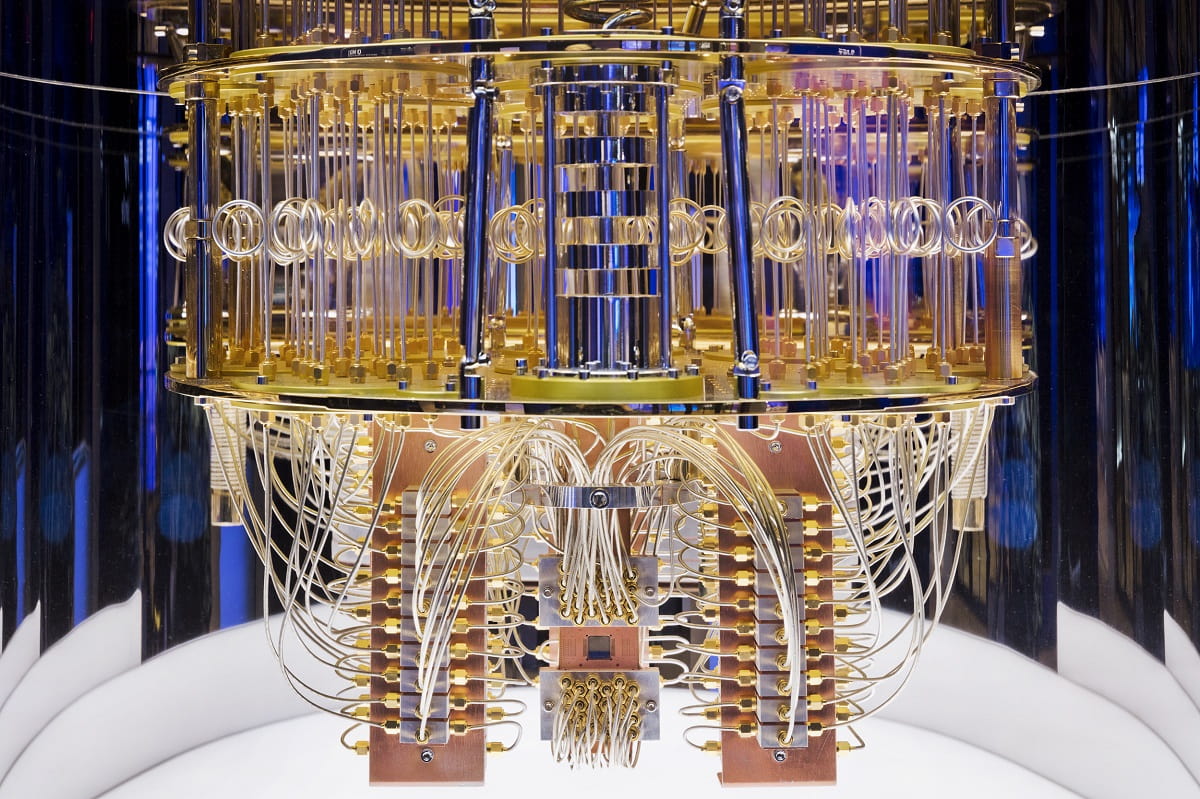

For most people, quantum computers are the stuff of science fiction. Based on shooting microwave photons at “qubits”, quantum computers are estimated to be far more powerful than any other computing system ever invented. So much so that cybersecurity experts are warning of an impending “Q Day”, where a functioning quantum computer renders the encrypted systems we use for banking, telecommunications and the military all but obsolete.

But quantum computers aren’t science fiction. Not only are they a key deliverable under Pillar 2 of AUKUS – the trilateral security partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States – they are being built right now. The Australian government has just announced an investment of nearly $1 billion to develop the first Australian quantum computer in Brisbane.

Yet what isn’t being mentioned in the ministerial press releases and media reporting is what is being done to ensure that this technology stays in Australian hands. There is a lot of secrecy around the deal, which hasn’t helped dispel unrest about precisely how Australia will protect this billion-dollar investment.

What are other countries doing about quantum?

Australia’s position is even more concerning given the steps taken by its allies.

The United States first published its quantum strategy in 2018, emphasising the need for “responsible and appropriate” partnerships in developing the tech. In May 2022, President Joe Biden signed a National Security Memorandum to the entire US government, demanding every department transition to quantum-secured cryptography and develop a coherent national strategy to protect quantum tech. China followed soon after, secretly recruiting top scientists in a bid to supercharge its investment in quantum tech.

The United States and China aren’t the only players in the space. In March this year, the United Kingdom finalised a report into regulating quantum technologies, emphasising a more secure approach to international cooperation. In Canada, an expert report by the Council of Canadian Academics has stated “building international collaborations may pose intelligence and security risks, or involve economic practices that may disadvantage Canada-based collaborators”. The European Commission has limited funding to non-EU countries, saying it is in the EU’s interest “to protect European research in these domains, the intellectual property that it generates, and the strategic assets that will be developed as a result”. Japan has also enacted a specific law to protect the domestically manufactured parts needed for quantum computing.

So, what is Australia doing?

Well, apart from the announcements about PsiQuantum’s investment, there isn’t a whole lot of clarity out of Canberra as to how this investment will be protected.

Firstly – and most significantly – Australia doesn’t have robust mechanisms for protecting its critical research. Despite the claims of some, a set of voluntary guidelines that only applies to universities won’t be enough to stop motivated nation-state actors from conducting espionage against Australia’s nascent quantum industry. Foreign spies are already after bleeding-edge quantum secrets in the United States, so it doesn’t seem a stretch to imagine the same thing occurring in Australia.

Secondly, Australian quantum policy is very vague on the details. The National Quantum Strategy describes “safeguarding national wellbeing” and “championing responsible innovation” but doesn’t say how Australia will actually achieve those goals. The secrecy around the tender, selection and funding of PsiQuantum hasn’t helped flesh out those details.

Thirdly, Australia is fast becoming the frontline in Indo-Pacific espionage. Threats of espionage and technological theft from China have been described as being at an “industrial scale”, but they aren’t the only players in the market. Recent revelations have emerged that India’s foreign intelligence agency was operating in Australia until disrupted by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO). Similarly, neighbouring countries such as Japan and Malaysia have been embroiled in recent espionage scandals, suggesting even Australia’s “friends” might not pass up the opportunity to get ahead in the quantum race.

If the Australian government intends to get serious about quantum technology, it needs to start thinking more deeply about protecting it. True, Treasurer Jim Chalmers did announce a shake-up to Australia’s foreign investment policies, promising a “risk-based approach” with appropriate “guardrails” around investments that might compromise national security. This should translate into stricter risk assessments and stronger compliance monitoring. Those same policy positions need to be replicated onto a technological security legal framework.

At the same time, Australia also needs a broader policy discussion about technological security. Quantum is just one of Australia’s critical technologies, alongside clean energy, artificial intelligence, robotics and biotechnology. But just naming Australia’s critical tech isn’t going to protect it from foreign adversaries who want to steal that tech – there needs to be bold and innovative steps taken by all sides. Government, academia, industry and the intelligence services all need to be at the same table, discussing the protections for Australia’s sensitive or high-risk research. If they aren’t, Australia’s once-in-a-lifetime “quantum moon shot” could be just $1 billion spent to hand over a quantum computer to somebody else.

Main image courtesy of Unsplash user Max. The views expressed are personal, and do not represent the university or any other organisation, agency or government.