Solomon Islands made international headlines last week, with the New York Times running a story, “China is leasing an entire Pacific island. Its residents are shocked”.

While the last part of the headline is not in question, the first part of the headline is doubtful. Reading through the four rather hastily put together pages that constitute the Strategic Cooperation Agreement for Tulagi island between the government of the Central Province in Solomon Islands and China Sam Enterprise Group Ltd, it becomes apparent that what is signed over for the Chinese conglomerate’s exclusive use lies well beyond the control of the provincial government. Minerals, fisheries, forests, land – these are all the domain of customary landowners with the central government as an abstract landlord for registered land and co-owner of minerals through the granting of mining licenses.

While it’s unlikely Xi Jinping will order a secretive Dr No–style lair be built on Tulagi island, the project might go ahead in some form, especially if China Sam Group manages to secure finance within China.

The provincial premier was also subsequently quick to walk away from the agreement following the New York Times publication, admitting during an interview with Radio New Zealand that “leasing Tulagi will not be possible. Nothing will eventuate on the agreement.”

Yet while it’s unlikely Xi Jinping will order a secretive Dr No–style lair be built on Tulagi island, the project might go ahead in some form, especially if China Sam Group manages to secure finance within China. If it does, the company’s lack of experience in the Pacific could lead to a scenario similar to the Pacific Marine Industrial Zone in northern Papua New Guinea, the first attempt by a Chinese company to set up a special economic zone in the Pacific.

There, local politicians and contractors are taking the Chinese company to the cleaners. Its management is holed up in an office in Madang as their funding from China Exim Bank is slowly frittered away on things like a 4 million kina ($1.7 million) gate.

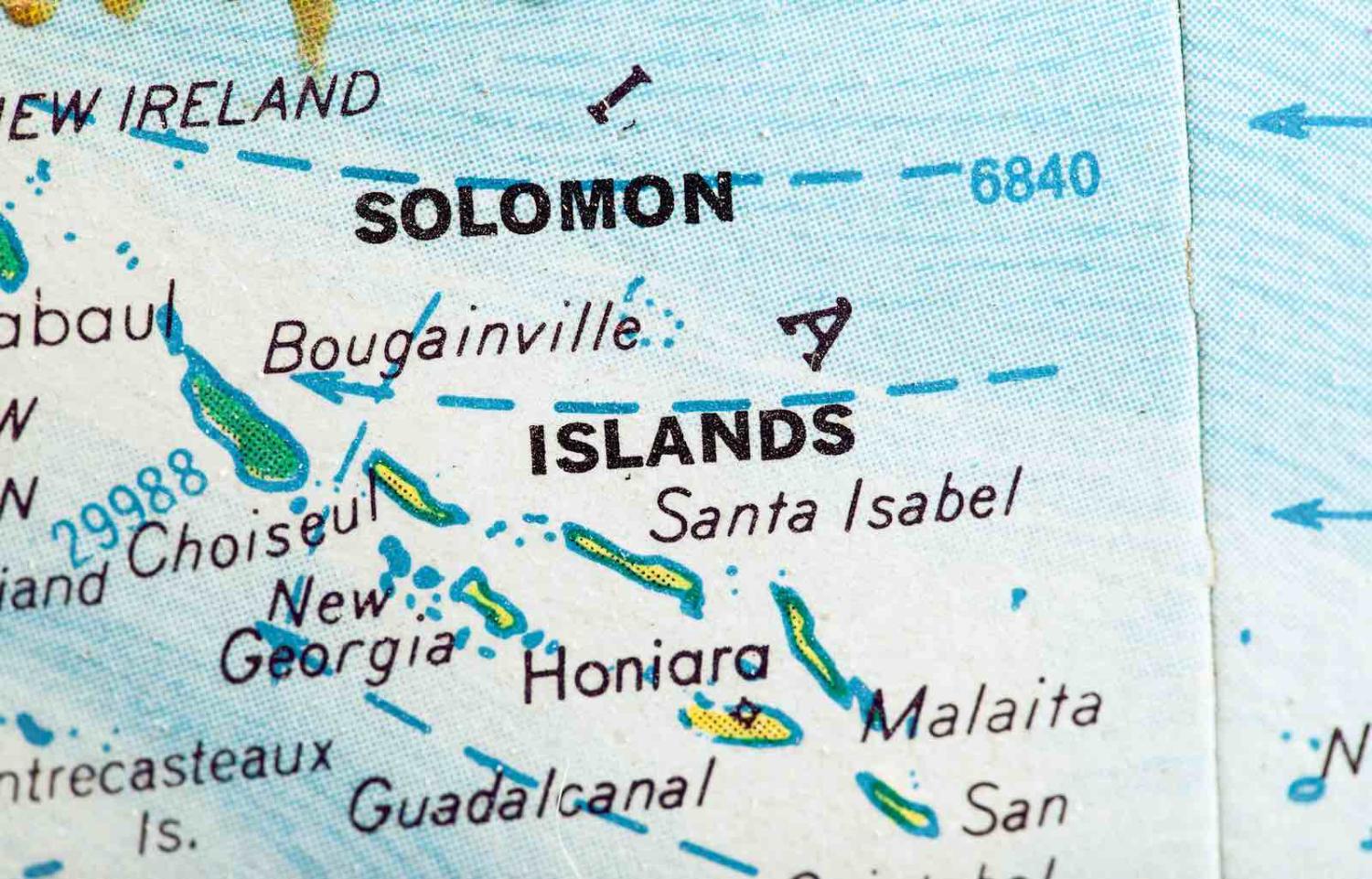

Unreported in major news outlets, another case suggests that the divide between national and provincial governments can cut both ways for China. On 17 October, the Malaita Provincial Government issued the Auki Communiqué, asserting a process that will consider the right to self-determination.

The trigger for the desire to push for self-rule by groups in Malaita was partly because the central government’s decision to switch diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China was perceived as a rushed process without much consultation with the people. Under “core beliefs and freedoms” the communiqué lists freedom of religion and “therefore [Malaita] rejects the Chinese Communist Party and its formal systems based on atheist ideology”.

The central government’s decision to switch to China had triggered a call by the Malaita for Democracy (M4D) movement and other groups for self-determination, asserting a desire to disassociate themselves from the diplomatic ties with the People’s Republic of China created by the central government and a wish to protect their land and natural resources from “unscrupulous investors”.

This call for Malaita independence and desire for self-determination has a long history. In the 1940s, the Ma’asina Ruru movement on Malaita attempted self-determination. In the 1970s, a Western Breakaway movement was formed, with Western Province boycotting national independence celebrations on 7 July 1978. The movement rose again in 2000 as the Western State Movement, leading to what was described as the “coup that no one noticed”. In 2015 the Malaita Provincial Assembly passed a resolution on Malaita sovereignty.

Malaita has a large population compared to the rest of Solomon Islands but has remained underdeveloped. Only 4.71% of land in the province is alienated, meaning the majority of the land and resources on Malaita are in the customary domain, under the control of the traditional resource owners. Despite this, the central government has control over the transaction tools and processes.

These instruments often favour investors, while resource owners are left as rent seekers and recipients of royalty payments. This contributes to a disconnect between decision-making at the national and provincial levels. The decision by the central government to switch to China and immediately invite PRC investors into Solomon Islands without input from the provincial government and resource owners demonstrates this disconnect.

The Malaita provincial government called on MPs to travel to Auki to participate in a leaders’ summit held on the 16 October to discuss issues surrounding the switch to China, including the call for self-determination. The Malaitan Provincial Assembly and five Malaitan MPs attended, with the communiqué issued the following day. Malaitan MPs who voted for the switch to China did not attend.

Malaita Province’s call for self-determination is not unique. Other provinces have raised similar sentiments, due to the concentration of power at the central government level without visible development happening at the provincial level. There are legitimate concerns arising on both sides, highlighting a fault line common in countries with federal systems of government.

Where limited authority has been devolved to the provincial level, scope exists for external actors to target weaker links in the national chain, leading to destabilisation. This may be for commercial gain or as targeted acts of economic statecraft.

Subnational governments are a softer target for influence operations, being subject to less media oversight and scrutiny by civil society. This may partly explain why heavily centralised countries such as South Korea, which also has ethnic and linguistic homogeneity, are largely impervious to PRC influence operations.

It is envisaged the switch in diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the PRC will bring development in Solomon Islands across all sectors. The central government should take a careful approach towards signing any agreements for such developments. Legislative mechanisms should be strengthened or reformed, to ensure the fault line between the central and provincial level is well managed and safeguard the interests of the people who are the owners of natural resources at the subnational and rural level.